Unless you happen to live near one, coal mines seem like a problem from another age. But mining coal in Appalachia, as Erik Reece documents in Lost Mountain, remains at least as destructive as clearcuts in Oregon or oil spills in Alaska. Reece makes a good case that, despite new methods of extracting black rock, modern coal mines are not much better than those of old Merle Travis songs, back when coal was as controversial as oil is today.

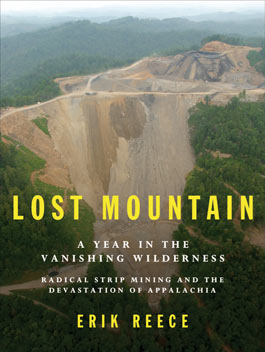

Reece, a Kentucky native, spent much of 2003 and 2004 watching a mining company “top” a mountain—dynamiting the peak off so the coal could be scooped out. Much of his state’s coal-rich east has been mined with this method, “blasted away with the same mixture of ammonium nitrate and diesel fuel that Timothy McVeigh used to level the Murrah Building.” A “topped” mountain does not cause the black lung pandemics and mine shaft collapses that killed thousands in the 20th century, but the new technology has brought a slew of new environmental problems.

Yet saving what’s left of the long-suffering coal belt lacks the political appeal of saving an untouched wilderness. A toxic spill at a Kentucky mine in 2000 was 30 times the size of the Exxon Valdez disaster but received virtually no national attention. “We’re just not quite as cute as those otters,” one resident put it. “The Prince William Sound was a pristine waterway,” Reece writes. “But the Appalachian mountains and its people were already considered damaged goods.”