Let’s be honest: No matter how devoted you are to The Wire, you probably don’t know much about life on the streets. While he was a sociology grad student, Sudhir Venkatesh acknowledged his ignorance, and walked into Chicago’s Robert Taylor Homes to conduct a survey on poverty. (Typical exchange: “How does it feel to be black and poor?” Reply: “Fuck you!”) He was detained overnight by drug dealers and set free with a friendly warning not to ask dumb questions. Seeing a unique opportunity, Venkatesh ditched the questionnaire and returned with a six-pack for the local boss, J.T.

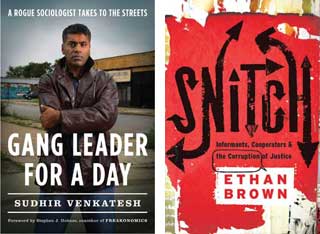

In Gang Leader for a Day, Venkatesh recounts how he came to earn the trust of J.T., a business-minded college dropout who explained the finer points of running a crack-dealing business. Venkatesh’s astute observations—that selling drugs on the corner pays less than working at McDonald’s, for example—garnered him a star turn in the book Freakonomics and established him as an unblinking chronicler of the underground economy. His latest book is the story behind his research, an almost thrillerlike tale of an earnest academic and his wary, streetwise sources.

Venkatesh admits that he hustled J.T. for information (and a career boost), just as J.T. hustled the addicts, squatters, and dealers in his domain. Ethan Brown’s Snitch also looks at the hustler-on-hustler dynamic, but in his disturbing tale, the hustlers are the cops and their informants. Severe mandatory minimum sentences for drug possession have created a situation in which the only way small-time dealers can avoid doing serious time is to cooperate with the police and prosecutors. They’re so keen to escape prison that they will point the finger at anyone. The potential for abuse is huge. Brown details the chilling case of a seemingly innocent Chicago man who received two federal life sentences largely due to the testimony of informants who claimed he was a major crack dealer. “The federal system is out of whack,” Brown writes. “People are being put away for the rest of their lives based on informants.”

When a “Stop Snitchin'” campaign gained national attention in 2004, the media and police saw it as witness intimidation. But Brown, who has reported extensively on the hip-hop underworld, says that it was motivated not just by a fear of local gangsters but also a quaint belief that dealers who get arrested should serve their debt to society instead of ratting someone else out. Too bad the extreme laws on the books make that a fool’s choice. Yet as both of these books unflinchingly reveal, surviving the streets often trumps practical, legal, or economic considerations. J.T. confides to Venkatesh that after years of climbing the ranks of the Black Kings, he sometimes thinks about going to prison just so he won’t be suspected of being an informant. Until then, “as long as I’m not behind bars and breathing, every day is a good day.”