Circuit Films/Zuma

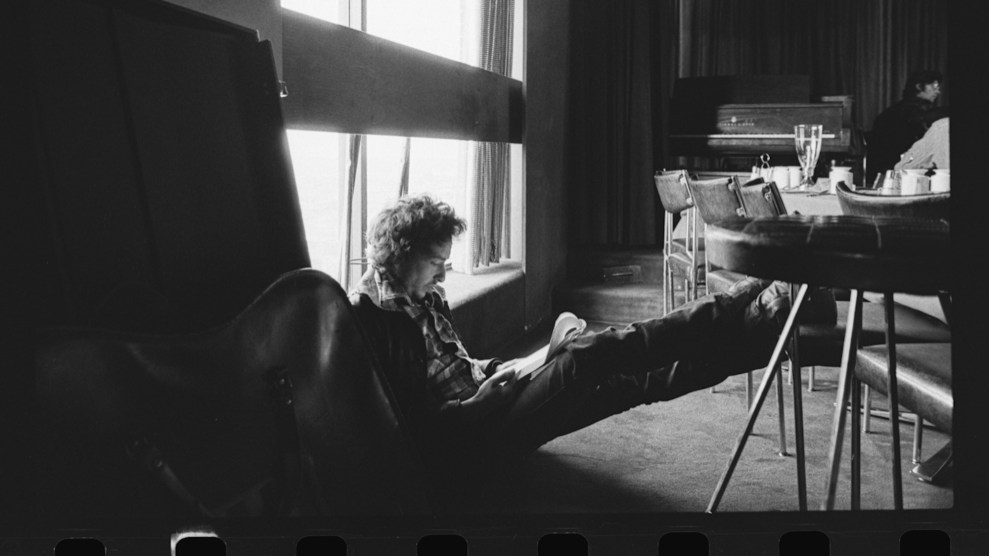

Around the midway point of Martin Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, now out on Netflix, the actress Sharon Stone tells a story. It seems that at some point in 1975, Stone had been invited to tag along with Bob Dylan and crew on his Rolling Thunder Revue tour. She would have been in her pre-famous teenage years at that point, but “she seemed old for her age,” Dylan reports in a latter-day interview, sounding less lecherous than baffled.

Backstage at one stop, Stone recalls, Dylan was messing around on an old piano. He called her over to play a song he said he’d written for her. She was moved to tears. Only later did she find out that “Just Like a Woman” was 10 years old.

Scorsese plays the moment for laughs. The lyric that had set Stone off at the time was, “She makes love just like a woman / But she breaks just like a little girl,” which is so on the nose that you can’t help but chuckle. But then you notice Stone is crying anew as she tells the story, and the note of cruelty in the gag becomes unmistakable.

And it is a gag. The movie is about the first leg of Dylan’s ragtag concert tour of the northeastern US in fall 1975, but to capture the spirit of the thing Scorsese melds fact and fiction. He conducts an interview with a made-up Dutch filmmaker who supposedly shot the film’s archival footage (when in fact the footage comes from a number of sources, including raw footage from Dylan’s 1978 experimental tour film Renaldo and Clara). He puts Sharon Stone on camera, even though she wasn’t actually on tour with Dylan and the incident she recounts never actually happened.

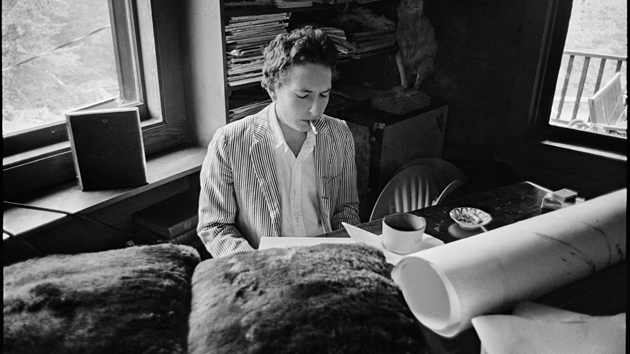

From the first scene of the movie—an antique-looking clip of a magician making a woman disappear—Scorsese wants us to know that we’re watching some mix of the real and the illusory. “You only tell the truth when you’re wearing a mask,” Dylan tells Scorsese at one point. The conceit plays off the shapeshifting musician’s famous tendency to fabricate stories with a small basis in reality; the viewer can never be sure what’s spoken is real, but each scene, supposedly, conveys some larger essence. And while the playful storytelling means Scorsese can’t be pinned down to any particular reading of Dylan or of his personal life, the movie, perhaps unwittingly, does tell us a lot about Dylan’s attitudes toward women.

As music critic Ellen Willis wrote in 1967, Dylan tended to view the women in his music in one of two ways: either “child-women, bitchy, unreliable, sometimes vulnerable, usually one step ahead,” or, conversely, “goddesses like Johanna and the mercury-mouthed, silkenfleshed Sad-eyed Lady of the Lowlands, Beatrices of pop who shed not merely light but kaleidoscopic images.”

Women featured prominently in the Rolling Thunder Revue and in the film, and they likewise show up here as either bitch-children or goddesses. In one scene, Patti Smith (goddess) recites poetry, and the camera pans to Bob Dylan, transfixed. In another, Joni Mitchell (also a goddess) sings “Coyote” at Gordon Lightfoot’s apartment, and the camera again pans to Dylan, softly strumming his guitar. Scarlet Rivera (bitch-child), who was then dating KISS’s Gene Simmons, played violin onstage with Dylan, and Ronee Blakley (unclear) sang backup.

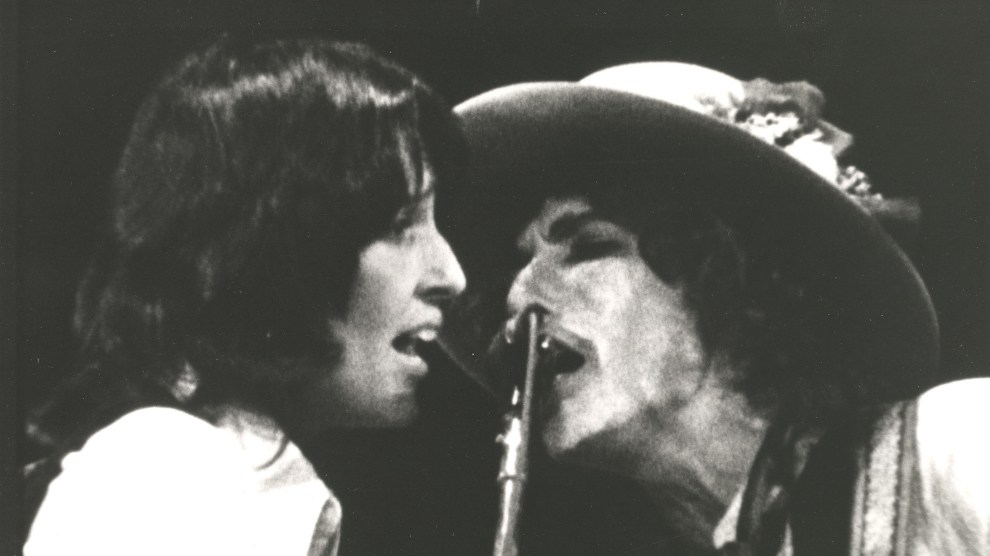

And then there’s Joan Baez, whom Scorsese interviewed for the film and who has the distinction of being both bitch-child and goddess in the Willis taxonomy. Archival footage shows her bantering with the audience about her relationship with Dylan. As Baez prepares to sing “I Shall Be Released” with Dylan, an audience member yells, “What a lovely couple!” Baez replies: “Don’t make myths. A couple of what?” Yet Baez can also be seen throwing her arm around her former lover onstage, laughingly playing into the rumor that the two were dating while Dylan coyly accepts her embraces. Mercury-mouthed but still a step ahead, she leads the audience to assumptions Dylan would rather not address.

One scene that appears to capture an intimate moment between Dylan and Baez is actually taken from Renaldo and Clara, which, like Scorsese’s documentary, smudged the boundaries between reality and fiction by blending concert footage with improvised vignettes. Baez asks Dylan what would have happened if they had wound up together, and Dylan replies, “I married the woman I love.”

That woman is Dylan’s first wife, Sara, who co-stars in Renaldo and Clara. She is absent from Scorsese’s film, her existence only hinted at. The year before the tour, Dylan had recorded Blood on the Tracks, which many critics say chronicles the disintegration of their marriage, though Dylan has denied the connection. Also absent from the film is Dylan’s most explicitly autobiographical song, the heart-wrenching “Sara,” in which he pleads with his wife not to leave him. Dylan performed the song 33 times between October 1975 and January 1976—during which time Sara also joined the tour.

Perhaps her absence from the film is due to a condition of her 1977 divorce settlement that she keep silent about her life with Dylan. But the picture of Dylan as a heartbroken family man would’ve been totally at odds with the Dylan of Scorsese’s film, the impish troubadour who invites along every beautiful woman who catches his eye, Sharon Stone (bitch-child) included. Certainly the tour itself wanted to project such an image. “The Rolling Thunder Revue was a caravan of gypsies, hoboes, trapeze artists, lonesome guitar stranglers, and spiritual green berets who came into your town for your daughters and left with your minds,” as Larry Sloman put it in his account of the revue.

While women were part of the revue, they and their politics were absent from its vision of social justice. Dylan’s “Hurricane” was a staple of the tour, but the big singalong closer, usually performed after “Sara,” was “Just Like a Woman,” antiracism and misogyny sitting side by side. “Just Like a Woman” was a bad song at the time, and it’s aged horribly. In “Just Like a Woman,” a woman is reduced to a sexual object: one who makes love, fakes pleasure, and in her fragility is subsumed by melancholy. In his chapter on the revue in The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan, Michael Denning notes that Baez and Blakley took turns singing verses of the song during the concert finale. It’s a strange choice for a closer, stranger still as a singalong for women, too.

Maybe the misogyny was also part of Dylan’s disguise, a mask to hide behind after baring his heart on “Sara,” a rare, personal track. (Remember that Dylan kept his second wife secret from the public until an unauthorized autobiography revealed her identity.) But for all the talk of the revue as a free-floating ideal political community, the choice of that song as the finale now seems pointed, as if the tour wanted to remind women to know their place.

But Scorsese doesn’t seem much interested in exploring the contradiction within Dylan’s and the tour’s politics. In fact, the movie seems to see women in much the way Dylan did—as bit players and supernumeraries floating through his life rather than as people, as characters rather than human beings. In Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, Dylan and Scorsese are the magicians making the women disappear.