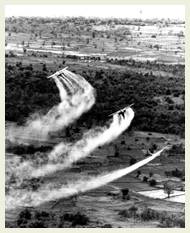

Image: AP/Wideworld

Deadly chemicals sprayed by US forces during the Vietnam war continue to haunt the people of Southeast Asia decades after the war’s end, according to a study published this month.

American researchers studied blood samples taken from residents of Bien Hoa City in southern Vietnam and found that the vast majority had elevated levels of a highly poisonous dioxin found in the chemical defoliant Agent Orange. (Mother Jones magazine investigated the legacy of Agent Orange in February 2000.)

“The really distressing finding for us was the fact that some of the children we were looking at, who were born long after the spraying had ended, had very elevated levels of these toxins,” says Arnold Schecter, a medical and environmental health researcher at the University of Texas School of Public Health at Dallas who headed the research effort.

The study, published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine focused on people living near a former American military base where Agent Orange was heavily used in 1971. Of the 20 residents Schecter tested, 19 had elevated amounts of TCDD, the poisonous dioxin in Agent Orange, in their bodies.

TCDD has been linked to cancer, immune deficiency, reproductive and developmental illness, nervous system disorders, endocrine disruption and birth defects. Researchers believe that residual Agent Orange sprayed during the war is leaching into the water throughout southern Vietnam, then moving up the food chain into humans, especially those who eat large amounts of fish. Schecter estimates that as many as one million Vietnamese may have been affected by the contamination.

Over the years, Schecter says, the US government has displayed no interest in studying how chemical spraying in Vietnam affected the health of the local people. But that seems to be changing. Under pressure from American veterans’ groups, Congress this year for the first time authorized federal money for research into the health effects of Agent Orange in Vietnam. The veterans believe the $850,000 appropriation could benefit American soldiers who were exposed to the herbicide if research in Vietnam finds further links between defoliant spraying and illness.

But almost as soon as it was appropriated, the research money was caught in a diplomatic dispute between American and Vietnamese officials. “Vietnam has linked any research there to payment of what they call humanitarian assistance to victims of Agent Orange,” says a State Department official who asks that his name not be used. The Vietnamese request, he explains, rankles US officials, who insist that all claims related to the war were settled in 1995, during the delicate negotiations surrounding the formal re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

For now, Schecter and his team are relying on private funding to support their research; they plan another trip to Laos and Vietnam this summer. “We had thought that Agent Orange was a part of history,” Schecter says. “But this research shows that in Vietnam, it’s not simply a part of history, it’s a current public health crisis.”