Image: AP/WideWorld

A team of scientists is providing new evidence confirming the devastating legacy of America’s chemical weapons program in Vietnam — a legacy which officials in Washington continue to question.

During a four-day conference in Hanoi this March, a group of Canadian and Vietnamese consulting firms unveiled research data showing how deadly chemical byproducts of the powerful defoliant Agent Orange continue to contaminate the soil, food and water in an isolated Vietnamese valley. The researchers further found that areas where large amounts of Agent Orange were spilled — particularly US special forces bases and dump sites — act as poisonous chemical ‘reservoirs,’ posing a long-term threat as the contaminants gradually seep into the surrounding lands.

American and Vietnamese officials signed an agreement during the March conference directing the two governments to cooperate on future research of Agent Orange. Still, while Washington is providing Vietnamese scientists with technical advice and some equipment to aid in the research, the agreement does not commit the US to provide any direct aid to help clean up the contamination — something Vietnamese officials say they will continue to pursue.

|

||

“We are not going to do any clean up,” said Dr. William Farland, the Environmental Protection Agency’s acting deputy assistant administrator for science. “We’re working to give them the tools they need to find hotspots of contamination and evaluate clean up technologies. We’re giving them advice, transferring technology, providing equipment and training. There is an issue as to whether we’ll aid in the clean up.”

Moreover, US officials continue to question the evidence linking Agent Orange usage to the dioxin contamination and to the myriad medical woes haunting the Vietnamese people — both those exposed to the defoliant during the war and those born since the conflict’s end.

“While the [new] research is useful in helping to outline the potential scope of exposure in Vietnam, it is very limited in providing any conclusive answers about health effects,” stated Dr. Anne Sassaman in a written response to questions. The director of the division of extramural research and training at the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Sassaman represented the US government in signing the research agreement at the March conference in Hanoi.

While acknowledging it is possible that US contributions to the study “may involve intervention activities,” Sassaman states that the program to which the US has committed “will be focused solely on research.” State Department spokesperson Brenda Greenberg confirmed Sassaman’s assessment, saying that the agreement signed in March details the full extent of Washington’s expected involvement.

Still, Vietnamese officials say they will continue to push the US to provide monetary support along with the technical guidance.

“We hold that anyone with a conscience would support our argument that while promoting scientific studies, it is necessary at the same time to carry out relief activities to overcome the consequences for the victims,” says Vu Van Dzung, a spokesman at the Vietnamese consulate in San Francisco.

American scientists have long known of Agent Orange’s deadly side effects. Long-term exposure to dioxin, a byproduct of one of the defoliant’s chemical ingredients, has been linked to cancer, birth defects, and degenerative diseases, such as spina bifida. As of 1998, nearly 6,000 US veterans of the war in Vietnam had qualified for government benefits to cover medical costs related to Agent Orange exposure. Vietnamese officials estimate that nearly a half million people have been killed or injured as a result of the contamination in their country, while another half million children have been born with serious health problems.

Still, little research has been done to determine the full extent of the contamination. The data presented at the March conference, the result of a seven-year study by Vancouver-based Hatfield Consultants Limited, lays out a chilling picture of a still-poisoned land.

Surveying land that was aerially sprayed and specific sites that were used for storage and supply facilities, the Hatfield scientists found extremely high levels of tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin at several locations in the remote A Luoi Valley, located in central Vietnam, along the border with Laos.

The highest level of contamination, the report states, was found at a former US Special forces base near the village of A So, located at the southeastern end of the A Luoi Valley. The levels of dioxin contamination found in A So — and at several other former US bases in the valley — were far higher than those found in parts of the valley that were only targeted by aerial spraying, the Hatfield report states. Soil samples taken in 1999 from A So, for instance, contained dioxin levels that exceeded acceptable levels established in 1998 by NATO by 85.7 percent, the Hatfield report states.

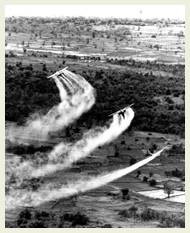

The United States Army began using herbicides such as Agent Orange as early as 1962 as part of a campaign to cut through Vietnam’s thick jungle canopy. Most commonly sprayed from C-123 cargo planes, the herbicides were used to uncover Vietcong camps and trails and to destroy the guerrilla army’s food supplies. The US military didn’t stop using Agent Orange until 1971, nearly two years after American scientists found that one of the chemical components used in the herbicide cause birth defects in laboratory animals and well after Vietnamese and American doctors began reporting a dramatic increase in unexplained ailments among soldiers and civilians exposed to the spraying. It is estimated that over 72 million liters of herbicide was used in Vietnam, and that Agent Orange was at one point sprayed over much as 10% of southern Vietnam.

The Hatfield scientists chose the A Luoi Valley because it has seen little development in the three decades since US forces stopped spraying Agent Orange. As a result, scientists were able to link the existing dioxin contamination directly to Agent Orange exposure. Still, the Hatfield team’s leader predicts that further reserach elsewhere in southern Vietnam will find similar levels of contamination wherever Agent Orange was used.

“The pattern of dioxin distribution in the A Luoi Valley could serve to mirror the situation of all of Southern Vietnam,” says Dr. L. Wayne Dwernychuk, vice president of Hatfield Consultants.

In fact, at least one other team of American scientists working in Vietnam have uncovered a pattern of dioxin contamination that supports Dwernychuk’s assertion. In March, a team led by Dr. Arnold Schecter, a professor of Environmental Sciences at the University of Texas, published the results of research conducted in Bien Hoa City, the site of a large US base.

In early 1970, 7,500 gallons of Agent Orange were spilled at the Bien Hoa base. Earlier that same year, three smaller spills were also recorded. More than 30 years later, the dioxin from those spills continues to contaminate the area, Schecter’s team found. In a paper published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, the group reported that blood tests on residents of Bien Hoa area showed a 207-fold increase in dioxin levels. “Usual blood [dioxin levels] in Vietnamese is 2 parts per trillion, and we found up to 413 [parts per trillion],” Schecter says.

According to the Hatfield report, the levels of dioxin contamination found at multiple sites in the A Luoi valley would be cause for immediate federal action if found in the United States. With Washington refusing to provide funding to support a cleanup effort, however, Dwernychuk says the poison will probably stay in the ground, a constant threat to residents across southern Vietnam.

“Basically, my assessment …. is that it will be a slow bureaucratic process that will not address the immediate humanitarian needs of a large segment of the Vietnamese population,” Dwernychuk says.