Photographs: Gary Fabiano

“Look what roads we’ve got in this country,” complains Eliahu as his big GMC van shudders on rough patches of Jerusalem highway. The van, admittedly, rides heavily. It’s weighed down by thick bulletproof glass clipped inside the original windows and steel plating to protect against Palestinian ambushes. Eliahu, an Israeli settler, makes his living providing safe transportation on West Bank roads. An Uzi and a fire extinguisher lie on the floor between the two front seats. We’re headed north, to the settlement of Ofra.

Heavyset, with a large crocheted skullcap and a beard, Eliahu talks passionately about “the commandment to settle the land” and punctuates sentences with “bless God’s name.” He’s what Israelis expect when they hear “settler,” what foreign photographers look for, but with around 220,000 Israelis now living in the occupied territories — up from 115,000 in 1993, when the Oslo Accord was signed — the settlers have expanded beyond the territory of stereotype. Often the only thing they have in common is the support they receive from the government.

Twenty minutes after we set out, Ofra’s yellow entrance gate slides open to let us in. Just beyond lies a girls’ high school, a clinic of Israel’s biggest HMO, and a park where a tiny wooden bridge arches over irrigation-fed rushes. On the side streets are two-story houses faced in white stone and topped by red tile roofs. Big pines tower over the homes, flower boxes line stone walkways, and a wooden wagon wheel leans against one home in a gesture of artificial rusticity. But for the Hebrew street signs, this could be a solid, middle-class American suburb.

Ofra, one of the first settlements in the West Bank, now looks positively suburban.

It’s telling that Ofra looks so normal. Established 28 years ago, Ofra marked a key success of the Orthodox nationalist Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful) movement to cement Israeli rule over the land conquered in the 1967 Six-Day War. “Ofra” became an Israeli synonym for extremism or idealism, depending on who was speaking. The community’s growth — from 1,200 residents in 1993 to more than 2,000 today — is an example of how West Bank settlements continue to expand post-Oslo. Ofra’s American-size homes within commuting distance of Jerusalem also represent a standard of living that few middle-class Israelis living within the Green Line — the border between sovereign Israel and the occupied West Bank — can afford.

A side road from Ofra winds past a vineyard and up a massive slope to where a string of weatherworn mobile homes stretches along a ridge. Home to 25 young families, Amona is one of 100 or so “outpost” settlements built since the late ’90s as a way to stake claim to more West Bank land. Yifat Ehrlich, a 25-year-old teacher at the Ofra girls’ high school, has lived on the peak for four years. Her parents and in-laws live in Ofra, where her family moved when she was 16. Ehrlich hopes to turn the “question mark” over the area’s status “into an exclamation mark” of Israeli rule. Israel’s survival, she says, depends on “extending its sovereignty to its natural borders.” Yet she stresses that, for her, living at Amona isn’t a “political act”; it’s a matter of staying in the area of her youth and developing it. “Ofra is the big city,” she says. “Here we’re building something new.”

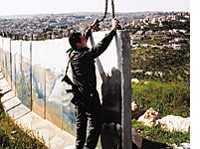

The nearby outpost of Amona offers a far more rudimentary lifestyle.

In that, the hilltop’s residents have help. Amona was recently linked to the national electricity grid, which requires Defense Ministry approval. The road to Amona was built by the regional council, which is overseen by the Interior Ministry. Israeli soldiers are stationed at Amona to guard it. The outpost’s perimeter is circled by floodlights put there by “the council, I think, or by Ofra,” Ehrlich says. Her voice trails off; she’s unsure of the details.

She’s not the only one. No one knows how much Israel spends on settlements — not the settlers themselves, not even government ministers or members of the Knesset. Back in the 1980s, a left-leaning cabinet minister told me that he tried to find out, only to hit a brick wall. In the early ’90s, spending on settlements became a major point of U.S.-Israel contention — but no reliable figure ever surfaced. Asked recently about settlement outlays, a Finance Ministry spokesperson told me, “We don’t have any way of making an estimation,” then suggested I contact “organizations that try to do that.”

Settlement critics say this fiscal uncertainty is largely due to what they call “creeping annexation.” Officially, the West Bank and Gaza Strip are outside Israel and under military occupation. But settlers are treated as if they reside within Israel, with most government functions handled by civilian ministries. The national budget therefore contains no chapter entitled “settlements” or “Judea and Samaria” (biblical names often used to refer to the West Bank). Instead, settlement outlays, tax incentives, and security costs are woven through the entire budget, spun into its fibers.

Of course, the right-wing administration of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon — himself a longtime settlement proponent — has little motivation to enumerate its financial support. But even settlement critic Yitzhak Rabin was unable to root out their sources of funding. As for the Knesset, Israel’s young political system hasn’t yet provided legislators with tools — equivalent, say, to the General Accounting Office or the Congressional Research Service — needed to unravel the web of settlement outlays.

Yet government support for settlements is a more pressing political issue than ever. Israel’s economy is imploding — largely as a result of the Palestinian uprising — and the government is slashing social programs and schools. Notwithstanding $10 billion in new aid from the United States, this spring the Israeli government said it was laying off 7 percent of its civil servants — including teachers — as part of an austerity plan, which set off national strikes. Furthermore, the new U.S.-backed “road map” for peace requires that Israel “immediately dismantle settlement outposts established since March 2001 … and freeze all settlement activity (including natural growth of settlements)” as a first step toward an agreement with the Palestinians.

Seeing an opportunity, Israeli opponents of settlement are stepping up their sleuthing efforts, surveying the dangerous countryside of the West Bank, digging through government maps and budget documents. If there is one thing that they and the settlers agree on, it’s that the fate of the settlements will determine the future of Israel.

Dror Etkes is 34, brash, fast-talking, with millimeter-length hair and blue-gray eyes. Now an activist in charge of the Peace Now movement’s Settlement Watch effort, he learned the West Bank’s countryside as a tour guide. For two years, he led educational seminars for foreigners — Americans and Germans, mostly — interested in Israeli-Palestinian political realities. “I wasn’t anti-Israel enough for them,” he laughs. “I don’t want to be the ‘enlightened Israeli’ they love. … Conceptualizing in black and white doesn’t help us here.”

On a late winter day, he picks me up in the schoolbus-yellow Kangoo minivan he uses to crisscross the West Bank. As we drive south, the cell phone clipped to the dashboard rings. On the line is a left-wing student from an Orthodox yeshiva, who tells Etkes that a notice on a school bulletin board is seeking residents for a new outpost. Etkes notes the location. Following a similar tip, he says, he recently learned of an outpost planned by the Gush Etzion regional council near Bethlehem. We’re headed there, one stop in a day of fact-finding.

Before entering the West Bank, Etkes pulls over and grabs two sea-blue flak jackets from the back. The Kangoo isn’t bulletproofed, and with Israeli license plates, it’s as much of a potential target for a Palestinian gunman as any settler’s car. The jacket, barely flexible, cuts into my thighs and chin. Our heads remain exposed.

Near the settlement of Neveh Daniel, we turn onto a narrow road to the Palestinian town of Nahalin, which the Israeli army has blocked with a mound of dirt. Etkes points across the valley below, to a beige strip extending from Neveh Daniel — a dirt road newly cut by settlers. We continue on foot across ancient terraces of olive trees, up a windswept hill, to the cinder-block house that the Palestinian Nasser brothers share while tending their orchards.

Three of the brothers, square-faced men in heavy jackets and stocking caps, meet us. We sit outside. “It’s much colder inside,” George Nasser apologizes. His mother and daughter build a fire out of branches to prepare tea. Two weeks earlier, he recounts, he saw men bulldozing the road, directed by a regional council staffer. The following day the bulldozer crossed the valley and pushed into his land. The Nasser family has deeds dating back to British times for 100 acres here, he asserts, but for a decade they’ve been fighting an order proclaiming it state land. They lost in the military courts last year and appealed to the Israeli Supreme Court.

With a letter from the State Attorney’s Office noting that the land’s status awaits a ruling, the Nassers’ lawyer managed to get Israeli police to stop the roadwork. But the regional council’s man returned and told them they weren’t allowed to work in the orchards.

“Do you know why?” Etkes asks.

“He said it’s state land,” Nasser replies.

“They’re trying to put a new settlement on your property,” Etkes tells him. He and the Nassers discuss legal options and how to alert Israeli journalists and left-wing Knesset members. There’s no fury in their voices, only the tired planning of the next round in a long fight.

Outposts, such as the one apparently planned for the contested land near Nahalin, are usually just a handful of mobile homes on strategic ridge tops, sometimes assembled by young radicals who grew up in the older settlements. It was Ariel Sharon who, back in 1998 when he was foreign minister, provided the impetus for the spread of the outposts. Returning home from the Wye River summit, where Israel promised to turn more land over to the Palestinian Authority, Sharon publicly told settlers that they “should move, run, grab more hills. … Everything that’s grabbed will be in our hands. Everything we don’t grab will be in their hands.”

Traveling through the West Bank, the function of the outposts becomes obvious: Hilltop after hilltop is marked with mobile homes. With only a small number of settlers, outposts create an Israeli civilian presence in the strips of land that the Oslo Accord left under interim Israeli control; they also separate Palestinian enclaves. Their legal status is hotly contested. Most foreign experts say that all settlements violate international law, which prohibits an occupying country from moving its population into occupied land.

Israel rejects that position, but does require government approval before any new settlements can be established. Yet nearly all the outposts have been established during the Barak and Sharon administrations, whose declared policy was not to allow new settlements.

Etkes admits that it’s hard to determine which outposts violate Israel’s own laws. Many are officially within the “town limits” of older, government-approved settlements. Even if they are far from the nearest house, they’re legally new neighborhoods of existing communities. In some cases, he says, town limits have been expanded ex post facto by the Civil Administration — the wing of the Israeli military that governs the occupied territories — to include a new outpost. But even outposts that are almost certainly illegal have been hooked to the national electricity grid, and regional councils — controlled by local settlers but enjoying government funding — build access roads and put up perimeter lights for their security.

Occasionally, when diplomatic pressure increases, or when Etkes and his cohorts draw attention to an egregiously illegal community, the government dismantles an outpost. In early April, National Infrastructure Minister Yosef Paritzky of the centrist Shinui Party — the most dovish group in Sharon’s governing coalition — threatened to cut off water and power to “about 10” illegal outposts, based on a list given him by Peace Now.

From Nahalin, Etkes and I head to a ridge to the south, where another yellow gate marks the entrance to the outpost of Pnei Kedem. The soldier in the guard booth glances at us, concludes we’re Israeli, and hits the switch to open the gate. “How many families live here?” Etkes asks innocently.

“Twelve,” the soldier says amiably. Inside, we find several dozen mobile homes. That could indicate more families ready to come, or be aimed at creating an imposing presence with few people. “There were 10 families a year ago,” Etkes tells me — a number he learned by signing up as a candidate to join the community.

Etkes’ investigative work also includes poring over settler newsletters and surveying the West Bank by small plane. But exploring on the ground, he says, is the most important source of information. “Without being in Netzarim,” he says, referring to an isolated Gaza Strip settlement, “I can’t come to the Israeli public and describe the reality it is subsidizing.”

Increasingly, peace now and other groups are also trying to describe the subsidy itself, the financial cost of the settlement project.

In a report last year, the Adva Center — a Tel Aviv social research group — looked at how government funding favored the settlements during the ’90s. One measure was road building: Per capita, three times more roads were built for settlers than for Israelis within the Green Line. Building bypass roads, political commentators noted, took precedence over solving Tel Aviv’s traffic jams.

Yehezkel Lein, a researcher for the B’Tselem human-rights group, has added more pieces to the picture. Lein, 33, is Argentinean-born; he came to Israel after high school out of “enthusiastic Zionism.” Initial exposure to the occupation, he says, shook his identity; eventually he reached “a balanced approach. … I can be very critical of Israeli policy without negating the inner core of justice in Zionism.”

At the B’Tselem office, Lein’s room is wallpapered with maps of the West Bank, including one he made showing that 42 percent of its territory — a number he learned only after threatening to sue the Civil Administration — is designated for settlement. “There’s tremendous cantonization of the West Bank,” says Lein. “From the beginning, the intent has been to break up the contiguity of Palestinian communities by building settlements and roads.”

Lein also sought to identify incentives used to encourage Israelis to move over the Green Line. A key mechanism, he says, is designating settlements as “national priority areas” — a category originally designed to help remote depressed regions but now being applied to settlements within commuting distance of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

So, using the “priority” label, the Industry Ministry offers incentives to investors to build factories in settlements. The Finance Ministry provides income-tax breaks. The Education Ministry gives teachers perks such as extra seniority, a benefit originally intended to attract staff to poor towns. The Housing Ministry, which subsidizes mortgages for first-time homeowners, gives larger loans at lower interest — with part of the loan turning into a grant if the buyer remains in the home for 15 years.

Another pipeline: Israeli local governments — such as regional councils — receive much of their funding from the national government. Using Interior Ministry audits, Lein found that settlements received 50 percent more per resident than did communities within Israel. Benjamin Ricardo, the Interior Ministry commissioner for Judea and Samaria, rejects any charge of favoritism. If settlements get more, he says, it’s because they have extra security needs. “We call it Oslo compensation.”

At the Housing Ministry, spokesman Kobi Bleich confirms that land designated “priority A” is offered to developers at half of market value. (Lein says that includes two-thirds of settlements.) The government covers the cost of streets and public buildings, an expense built into the price of homes within the Green Line. The ministry also subsidizes mortgages provided through commercial banks — an arrangement that means even the buyer may be unaware of the size of the subsidy. Using a “mortgage wizard” on a ministry website, I found that a family of three would get a government-backed mortgage of less than $20,000 to buy in most Jerusalem suburbs inside the Green Line — a small fraction of the home’s cost. But the government would provide that same family more than $40,000 to buy in Ofra, one-sixth of which eventually converts to a grant.

Starter homes — which are hard to find in Israel — are available in the settlements, where money buys more. At Shilo, 750-square-foot houses are available for $60,000, with the option to expand, according to a member of the settlement’s secretariat. “You won’t find a house that size at all inside the Green Line,” says economist Yair Duchin.

The ability to buy more house for less, rather than strongly held political ties, has attracted many Israelis to the so-called quality-of- life settlements — large suburbs built near the Green Line since the 1980s. But it also helps settlers to become homeowners at an early age and have bigger families. Settlers view large families as expressing a commitment to living for others. But affordable housing makes it easier to realize those values. Intentionally or not, subsidies encourage not only migration to settlements but the creation of a large second generation — a factor worth remembering when government spokespeople argue that new settlement construction is needed because of “natural growth.” Ultimately, subsidies allow the settlement movement to turn its ideology into reality.

Looking for the full costs of settlements, Peace Now hired economic consultant Dror Tzaban. A former Finance Ministry official adept at deciphering budget documents, the 44-year-old Tzaban spent three months last year analyzing Israel’s 2001 budget. When we meet at a suburban coffee shop outside Tel Aviv, he still looks the part of a ministry salaryman: close-cropped hair, pale-blue shirt open at the collar, binder full of documents. He speaks in the tone of an accountant, not an angry activist.

Dryly, he begins by describing the numbers he couldn’t get. “The defense budget is a black box,” Tzaban explains; the breakdown is classified. Yet some piece of the defense burden is due to settlements. “The army guards settlements. It costs more now, because the situation is worse, and because there are more outposts.” Where a settler has been ambushed, the army may level a hill or uproot a Palestinian orchard to remove cover for attackers. That costs money, Tzaban says.

There’s also the drag on the nation’s economy. Three hundred soldiers guard Netzarim alone, he says — reservists who’d otherwise be home working. “So the economy loses 300 work years” annually, up to $15 million in lost production, on that settlement alone.

In civilian realms, the budget often isn’t broken up geographically, so there’s no way to tell how much the Environment Ministry spends in the occupied territories, or what portion of welfare benefits goes to settlers. Still, there was plenty Tzaban could find. “The picture is very clear,” he says, leaning toward me over the table, just barely approaching passion. Income-tax breaks for settlers cost almost $40 million in 2001. Extra payments to local governments cost $150 million. Outlays on roads totaled another $95 million. And add in subsidies for housing in settlements and for industry, for water and sewage projects, even for “tourism development.”

Altogether, Tzaban found an extra $430 million spent on settlers — $2,000 per person — in a country where the gdp per capita is only about $17,000. And Tzaban stresses that this is only a piece of a much larger, unknown total.

In part, the continued support for settlements results from deliberate policy decisions. But “institutional inertia” is equally important, says political sociologist Lev Grinberg of Ben-Gurion University. The decision to assign settlements to civilian ministries was made years ago, largely as administrative convenience. Treating settlements as part of Israel wasn’t so much debated as taken for granted. And, once created, incentives for settlers remain from year to year. To stop the momentum, Grinberg asserts, “you’d have to take very strong action, which hasn’t happened.”

Today, though, Israel’s budget leads the public agenda. The economy has shrunk by 1 percent each of the past two years — the worst downturn in the country’s history. Tourism revenue has vanished, and with tax revenues plummeting, Sharon’s new government plans massive new bud- get cuts. By late May, it was unclear how the belt-tightening would affect settlements. Initial reports said the budget would reduce subsidies for home buyers in settlements. But the Housing Ministry’s Bleich told me that the aid will remain, even if how it’s provided changes. The new budget requires a reduction in income-tax breaks to residents of priority areas, but leaves it up to Finance Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — a defender of the settlements — to decide which areas will receive the remaining benefits. Meanwhile, during the Iraq war, the U.S. Congress appropriated an extra $1 billion in military aid to Israel this year and $9 billion in loan guarantees over three years. Overall, even if the budgetary pie is smaller, the settlements are still likely to receive their slice.

In the midst of the budget debate, I asked Welfare Minister Zevulun Orlev about settlers’ tax benefits. Orlev is a leader of the small, pro-settlement National Religious Party. “In principle,” he says, “someone who’s in a priority area, someone who’s in a war area, certainly should get preferential treatment.” Asked why the settlements should be there, he answers, “To fulfill the commandment of settling the land of Israel and the vision of Zionism.” He pauses. “What’s not clear here? For the same reason people created Tel Aviv…. We see Judea and Samaria as an inseparable part…of the state of Israel.”

Those words point to the essential philosophical dispute underlying the economics, a dispute between two opposing concepts of the state of Israel. In one view, Jews and Arabs are battling for hegemony over an indivisible land that stretches from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River. The Israeli right sees this view confirmed by Palestinian rejection of then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s proposals at the Camp David summit in 2000, and by subsequent terror attacks within the Green Line. Palestinians also want it all, say settlers and their supporters, so “it’s us or them.” As they see it, it is only natural for the state to help those who are on the front line.

For opponents of settlement, Israel stops at the Green Line. The goal of Zionism was the creation of a democratic state with a Jewish majority, and the division of the land at the time of Israel’s founding was not an accident but a necessity. Partition remains necessary, they say, despite acknowledged security risks.

As Etkes notes, settlers don’t simply want to live in the land “where the prophet Amos wandered with his sheep”; they want to do so under Israeli sovereignty. “That requires annexing [the occupied territories] and integrating the Palestinian population politically and economically as citizens,” he argues. The result would be a binational democracy, like Belgium. “That might sound ideal in theory,” he says, “but let’s climb down from theory. Right now it’s clear that the two [peoples] aren’t capable of living in the same state.”

The alternative is “a system of de facto apartheid, which is what’s happening today.” Or, he says, Israel can relinquish the occupied territories. To invest in settlements, from this perspective, is to drain a state on the verge of bankruptcy for a project that will cost Israel either its democracy or its Jewish character — or will be abandoned.

On the road with etkes, in the dry hills northeast of Jerusalem: The name Neveh Erez is carved into a weathered plank pointing off the highway, as if it belonged to some Hebrew-speaking corner of Wyoming. A ring of floodlights surrounds the prefab houses of a ridge-top outpost. As we climb out of the van, three big, quiet dogs greet us, followed by their owner: a ponytailed man in jeans, a white T-shirt, and a corduroy jacket, with pale-green eyes, an instant, soft smile and a softer voice, who asks us if we’d like coffee. His name is Noam Cohen. He knows Dror Etkes. He invites us in anyway.

On one side of his mobile home, Cohen has built a deck decorated with bamboo wind chimes and flowerpots. Drip-irrigation tubes feed saplings on the hillside below, which leads down to pens holding geese, chickens, sheep, a donkey. Another wagon wheel, stuck in the ground, looks like it belongs. Inside the living room is a drum set and a guitar, and Rajasthani tapestries with dangling pennants hang over doors and windows. Cohen guides us to the deck.

“You’re fulfilling the commandment of settling the land of Israel,” Etkes says sarcastically.

“We’re fulfilling our dreams,” Cohen calmly corrects him. He brings out Turkish coffee and chocolate-chip cookies. Cohen, 35, was born in a working-class Jerusalem neighborhood. He finished high school after his army service, then worked as a youth counselor and dreamed of settling in the desert with his best friend, to farm and create a school for troubled teens. Several years ago, they were preparing to homestead in the Negev, within the Green Line. Then an environmental group went to court to block all homesteading in the area.

Helped by a settler organization, they came here instead. Officially, Cohen says, Neveh Erez is part of an existing settlement, one and a half miles away. According to Etkes, though, it is beyond the town boundaries as marked on Civil Administration maps. For Cohen, it didn’t matter which side of the Green Line he was on. His ideals have to do with a simpler life, using wind and solar power, helping kids. He’s been here four years; he makes his living partly as a musician. His wife, Tehilla, is an artist.

The ridge, he says, is state land, designated for settlement. The outpost has almost completed the checklist of official okays — except for the final signature from the deputy defense minister, which will make the place fully legal. The regional council erected the perimeter lights, “I think with Housing Ministry funds,” Cohen says.

“The Palestinians say the new mobile homes are on land that belongs to them,” Etkes tells him.

“That’s why there are courts. They’ll decide,” Cohen replies. The conversation is calm. Cohen asks, “Why don’t you support us?”

“Because you are making an apartheid system permanent,” Etkes replies. They argue over whether all Palestinians reject compromise, and why the peace talks collapsed. “We never even reach the issues of Jerusalem and the Palestinian refugees,” Etkes says, “because your presence here shows unwillingness to partition the land.”

Cohen demurs: Let there be a Palestinian state, but this is a Jewish area, he says. Etkes and I thank him for coffee and drive out. “As much as politics needs us,” Etkes tells me, “we need politics, to say we did something against all this.” Etkes has a dream, I think, and Noam Cohen has a dream, and so do the residents of Ofra. Each insists the other’s dream has too high a price. And Israel must decide which dream it can afford.