Photo: Antonin Kratochvil/VII

Around Pakistan’s Independence Day, last August 14, billboards sprang up on roundabouts in the city of Karachi offering three different Kentucky Fried Chicken meals. Against the green and white flag of Pakistan, they bore the words “A free nation free to choose.” That morning in the Abdul Baqi madrasa, or religious seminary, 350 students were gathered for a special Independence Day assembly. Fifteen-year-old Rafi Udin spoke to the rows of boys, all wearing blue uniforms with white caps. The youngest sat in the front, the oldest in the back. A fiery orator, Rafi explained that before India had been divided and Pakistan created, Hindus had stolen control of India from Muslims and deprived them of their rights. They had treated Muslims as the enemy. “In fact,” he said, “at the end of the 19th century it was very common thinking that Muslims are neither human nor a nation.” Rafi ended with a triumphant cry of “Pakistan Zindabad!“—Long live Pakistan!

What to do with madrasas like Abdul Baqi was among the most controversial issues facing Pakistan when I visited last summer. They had been accused of churning out terrorists and providing a medieval education. The Taliban had been formed in Pakistani madrasas, and the word “Taliban” means students. Madrasas had been accused of sending their students to fight jihad. In the wake of 9/11, Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf had warned that he would bring the madrasas under control and end the preaching of hate. Following the July 7 London bombings, his security forces had arrested hundreds of militants, provoking a wave of protests that turned into riots.

The Abdul Baqi madrasa countered accusations of extremism by supplementing the rigorous Islamic education that its students received with a secular curriculum including English, math, science, history, and computers. Its director was Maulana (teacher) Tufail Ahamd, grandson of the school’s founder and himself a graduate. I asked him what jihad was. “When the enemies come to your country, then the government has to announce a jihad,” he said, “an emergency to fight the enemy. You have to defend yourself.” So there was no individual responsibility to fight jihad? I asked. “The government has the resources and security forces,” he said. “Their duty is to fight the enemy and secure the country.” I asked what he thought of madrasas that urged children to engage in jihad. “It is wrong for a madrasa to encourage jihad,” he said. He lauded Musharraf’s efforts to crack down on fundamentalists.

As I spoke with Maulana Tufail, he received a note from an officer of the Pakistani police’s special branch asking him to forbid us from taking photographs of the buildings. The undercover police had been following our car since we arrived. The maulana invited the officer in for tea to see that our conversation was harmless. The officer later asked us for a ride back to his car.

THAT MORNING IN AN OFFICIAL STATE CEREMONY, a wreath had been laid at the mausoleum where Pakistan’s independence hero, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was buried. Tens of thousands of people stood outside its gate and in the immense white courtyard, where Jinnah’s body lay in a domed tomb. Some of the pilgrims had painted their faces the national colors, green and white. On the street thousands danced to Indian disco music. Children ran around, and the mood was chaotic, but peaceful. As we visited the mausoleum our uninvited special branch escorts asked us if they had time to get gas for their vehicle.

In Karachi the celebrations ended without incident, but in Balochistan, the largest of Pakistan’s four provinces, Independence Day brought trouble. A series of bombs rocked five well-to-do neighborhoods in the capital, Quetta. There were also explosions in railway stations, airports, government installations, and power plants, as well as small-arms fire against military checkpoints. Members of the Baloch minority, after whom the province is named, were spotted wearing black armbands in protest.

When I arrived in Quetta, the two university students who introduced me to the dusty town were terrified of Pakistan’s Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and other “agencies.” They worried that my hotel room was bugged and asked me to turn the television up high while we spoke. They worried that once I left they would be harassed or punished for associating with me. Nevertheless, they took me to the Quetta Press Club, where Baloch activists were protesting the jailing of three of their comrades. In a parking lot outside the press club, two dozen hunger strikers sat silently on carpets beneath a tent. They were members of the Baloch Student Organization (BSO), which had about 6,500 members and often used the image of Che Guevara. Two emaciated men were lying down with IVs containing glucose hanging above them. They had chosen to strike until death. In a weak voice, one of them explained to me that “hundreds of people are captured by the agencies, but the government denies it.”

Seated next to the strikers was Dr. Allah Nazar Baloch, a representative of the BSO (many Baloch activists take the name “Baloch” as a gesture of solidarity). I asked him who had arrested the three men. “There are a lot of agencies and we do not know which one,” he said. “There is no democracy in Pakistan.” He explained that they were seeking the independence of Balochistan. “They do not treat us like a nation, or humans. The government is taking our resources—gas, gold, the deep-sea port.”

As Dr. Nazar was speaking, a man in his 60s arrived to introduce himself as Dr. Abdul Hayee Baloch, president of the National Party (Balochistan). The National Party did not call for an independent Balochistan, he said. “We stand for Pakistan as a multinational state. It should be a real federal parliamentary system. Now it’s total dictatorship. There is no rule of law, no constitution. There are arrests without charges.” He complained that in Pakistan, a few thousand families controlled all the wealth.

Dr. Nazar of the BSO interjected, telling me that it was Punjabis who control everything. Dr. Hayee snapped that he should not interrupt his interview. They began arguing in English, then switched to Balochi. “We struggle just for Balochistan,” Dr. Nazar told me. “We are slaves.” Dr. Hayee jumped in, “The whole country is slaves.”

On the other side of the tent was Dr. Imdad Baloch, chairman of the BSO. On March 25 he had been arrested along with six others, all BSO activists, who had gathered in a Karachi apartment. At midnight a knock had come, and several dozen men in uniforms had taken the group to a detention center. “They asked, ‘Where are you keeping arms and ammunition?’ But we are just students. They beat us with leather or rubber. We were kept in a cell the size of a box and we did not see the sky.” After two months, four of the men were released, but there was still, in August, no news of the remaining three. I asked Dr. Imdad if he thought they could achieve independence through hunger strikes. “We will succeed by our courage,” he said somewhat unconvincingly.

That day, the union of newspaper sellers in Quetta called a strike to protest the arrest of several of its members for selling publications that had recently been banned. The vendors sat in front of their shops, drinking tea. One old man blamed America for the ban on radical Islamic publications. “Musharraf is the agent of Bush,” he said. He complained of the double standards he saw: “Our army preaches jihad in the name of Allah,” he said, “but newspapers cannot.” Another seller fretted that “we did not get a list. We don’t know which books are banned. We are afraid.”

The following day, when the newsstands were open again, I returned to see what they were selling. Alongside books and journals with inviting pictures of Indian pop stars was a book entitled In the Grip of the Jews. On its cover was a snake with a Star of David slithering around the American flag. Another book cover depicted an American hand holding a cobra and giving it to a Muslim hand, while the Muslim world was shown in crosshairs. I managed to purchase two magazines that everyone seemed to agree were banned. One was called Way of Faith, and this particular issue was dedicated to the battle of Fallujah, which had become mythic throughout the Muslim world. An article claimed that hundreds of Americans had been killed in Fallujah, but the American government was silent over its losses, which were like Vietnam. There was a summary of 10 Koranic chapters that discussed jihad. Statistics were provided for the daily deaths of allied forces in Iraq.

I also purchased a weekly magazine called the Friday Special, published by the Jamaat-e-Islami political party. Its cover depicted Pakistan as a tree from which hung the “fruits of secularism,” such as music, dance, Western television channels, the promotion of pornography, changes in Islamic textbooks, the crackdown on madrasas, and the cancellation of religious publications. For a reason I could not divine, the characters of The Simpsons were standing next to the tree.

As I was going through the newspaper stands, I noticed a man with a mustache and nicely pressed clothes asking the shopkeepers what I had asked them. Later, in a clothing store, I noticed him again, browsing without interest through children’s apparel. When he realized I had spotted him, he hurriedly entered a building.

THE JAMIAT ULEMA-E-ISLAM (JUI) is one of Pakistan’s most radical and powerful religious parties, seeking to purify Islam of Western influences. The JUI spawned the Taliban, and supported it both before and after it took over the Afghan government.

Walking to the JUI offices in the old section of Quetta, I passed by a group of children tossing a tennis ball. The ball would bounce into the open sewage canals on both sides of the street and one of the kids would reach in and fish it out, squeezing it between his hands to drain the sewage water out. The party office was adorned with the JUI’s black-and-white-striped flag and images of machine guns. Posters showed blood and an American hand holding Musharraf’s hand while plunging a knife into Pakistan. Another poster showed an armed mujahid. It read, “Wherever Muslims are killed, America is responsible.” Nur Muhamad, who led the JUI in Balochistan, was seated outside on a mat. A member of the National Assembly, he wore a white turban with a white shalwar kameez and a long white beard. His eyes were gentle and sad, his fingers thin and manicured. I was led into a separate room where we sat down on thin mattresses, leaning against stale pillows. We were served sweet tea in short bowls.

“We want an Islami Nizam,” or Islamic system, he told me. “A Muslim country needs a Muslim government.” The Koran would be the law, and every decision would be made in accordance with its teachings. The government would be composed of Islamic scholars. There had never been a government like this, he said. Had the Taliban not been one? I asked. No, he said. “The government in Afghanistan came to power by jihad, and we want to elect the government.” Nur Muhamad’s party was attempting to pass a Shariah bill instituting Koranic law through the provincial assembly. They controlled the North West Frontier Province and, in what some Pakistanis called “Talibanization,” had implemented such a bill there. Already in Balochistan, stores selling American and Indian movies were being attacked and movie posters torn down. People playing music in public were harassed. “Our people are very angry at the U.S. government,” Muhamad said. “Musharraf is following Bush. He is an agent of the U.S. government.” During the crackdown on madrasas, he told me, “the government arrested girls and boys and injured them. The Bush government has a plan to arrest all students of Islam so that people will be scared to follow Islam.”

The next day, a large swath of Quetta shut down as the town’s Shia residents buried a shopkeeper named Anwar Abidi, who had been shot by a man on a motorcycle as he was walking home. Hundreds of police guarded the streets and stood atop the mosque walls. All the shops were closed.

The imam of the mosque where the funeral was held, Alama Maqsud Ali Domki, wore a white turban and a black cloak over a brown robe. He said sectarian killings had become commonplace over the past 25 years. Sunni scholars “give orders to kill Shias,” he said, adding that in this they were supported by the Pakistani right wing and Al Qaeda, “as well as colonial powers like Israel.” He said the courts never convict the attackers and complained that there were still many Taliban living in Quetta’s Pushtun areas. Most people, including the police, seemed to agree that extremist Sunni parties banned by Musharraf were responsible for the killings.

When I returned to my hotel for lunch, a well-dressed man was standing alone in the restaurant entrance. He asked the waiter to take several pictures as he stood stiffly and without expression. The background was me. After lunch, when our car pulled out, I saw the same man hop on a motorcycle and follow us around town from a distance. Whenever our car stopped, the motorcycle would continue on a bit and wait, pulling back into traffic when we passed.

That day I visited Tahir Muhammad Khan, the former chair of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan and a government minister in the 1970s. He was a lawyer by profession as well as an amateur historian. I mentioned that I had just returned from the Shia funeral. There had been three sectarian killings in the last three months, he said, and I asked to what he attributed them. “The system is responsible,” he said. “You, the Americans, you created these problems for us. You gave us the money, the weapons, the Arabs.” Khan blamed the sectarian killings on the culture that had resulted from the Afghan jihad, which had drawn thousands of young radicals from the Gulf to the region. “People from petrodollar countries encouraged Afghans to become more conservative,” he said. “They wanted to make them as primitive as possible. The British, America, and Israel also did this. Mullah rule came to Iran, so the United States wanted to use the Arabs against Iran.” Khan, himself a secular Sunni, explained that Shia Islam tended to be more democratic than other forms of Islam, and that the autocratic Sunni regimes feared this—”the idea was that if Shia rule spreads, many crowns will fall”—and so they promoted anti-Shiism. “Today you are reaping what you have been sowing. Pakistan was a liberal society. We had openness, music, a culture of dance.” All this changed in 1979, he said, when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan and the jihad began. Now, Pakistani culture was ruined. “We have 18 religious television channels,” he complained. “We have been preaching jihad for 30 years.”

Musharraf’s government was only making cosmetic changes, he said. “Musharraf is a good stooge for you. He wants to preserve the status quo. The army thinks it can finish the mullahs and nationalists.” Yet, he noted, the military had helped arm the sectarian groups to begin with, to use them as proxies in Kashmir and Afghanistan and against the domestic opposition. Khan blamed the local culture for not respecting the individual. “Going back to the Mughal era,” he said, “the citizen was reduced to the size of an ant. We are flies, small flies. Whoever has a gun is a warlord, and the army is the most organized warlord in Pakistan. Islamabad is ruling strictly by the gun, and this is the reaction to it.” Wasn’t he scared of being so vocal in his criticism? I asked. “It can happen at any time,” he shrugged. “When you live in a primitive society, death can come at any time.”

That night at dinner, the man from the newspaper stands and clothing shop was sitting in my hotel’s lobby with his driver. I walked up and invited them to dinner. The well-dressed man laughed in nervous denial while the driver glared at me. I told them I would not be leaving the hotel until 10 the following morning and wished them a good night. In the morning I was awakened by a phone call. “Mr. Rosen Nir,” said a man in good English but with a strong accent. “I’m calling to inform you that people are after you. We know exactly what you are doing, and if you do not leave the area, the consequences will be like Daniel Pearl.”

BACK IN KARACHI, where Daniel Pearl had been abducted and slain in January 2002, I visited the Binori Town madrasa, one of the initial centers of jihad in Pakistan, preaching and recruiting fighters for the war against the Soviets in the 1980s. Following September 11, 2001, its preachers praised Osama bin Laden, who had been an associate of its then-director. Pearl’s kidnapper, Omar Sheikh, was said to have stayed at the Binori Town madrasa. The madrasa was considered a center of the Deobandi, a movement founded in the 19th century that is similar to contemporary Saudi Wahhabism in its puritanism and in its view that Muslims with differing interpretations, especially Shias, are infidels. In response to the overt anti-Americanism preached in the mosque, its imams had been warned by the police to avoid politics in their sermons.

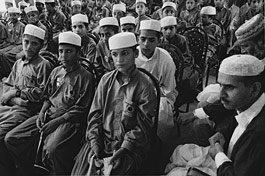

Past the entrance to the red mosque, the light-skinned photographer I was with drew hostile glares from young men with wispy, immature beards. A murmur rose from the white courtyard as children rocked back and forth, repeating sections of the Koran that they could not understand, since they knew no Arabic. This was hefs, the initial part of the madrasa education, often taking three years; only after a child had memorized the Koran could he begin to learn what the words meant, what the prophet Muhammad had said and done, and how scholars explained it all. It took about eight years to complete these initial stages. Among the entranced children, swaying like Orthodox Jews at prayer, I spotted Asian and African faces.

I was met by Maulana Shoaib, an administrator and teacher. I asked him what jihad meant to him. “When non-Muslims see the life of Islam and see the love and affection it teaches,” he said, “they automatically become Muslims. But if non-Muslims say, ‘No, we won’t live with you or allow you to spread Islam,’ then fighting is the last resort for a good Muslim with the help of Allah.” In the past, students from his madrasa had gone to fight in Afghanistan during their summer vacations.

Dr. Abdul Razaq Sikander had been director of the school since his predecessor was murdered. Sikander had gold-rimmed glasses and a beard stained red with henna. We spoke in Arabic. He asked why it was that Jews and Christians in America were allowed to choose their own religious education, but his government was cracking down on madrasas. I told him that there was global concern over radical Islam in Pakistan, especially since three of the July 7 London bombers had been Pakistani. “July 7 was a big conspiracy just to accuse Pakistan,” he said. “There is no proof who it was, and they were from the U.K.” He expressed sympathy for the victims of September 11, condemning the attack. “According to the Koran, Jews are the enemy, but Muslims and Christians are close,” he said.

As we finished, Sikander walked me out of his office to the courtyard, where the children were on their noon break, sleeping in ordered rows on the hard floor, arms swung over their eyes for shade. He didn’t see any problems with the strictly Islamic education his madrasa was providing. “If he wants to be an alim,” or scholar of Islam, “why does he need math or other education? Ask a doctor why he is not studying law. The education we provide comes from heaven. It is better than all other educations.” (A former head of the ISI, Asad Durrani, offered a laissez-faire version of this argument, telling me there were about 20,000 madrasas, of which no more than 250 were “bad.” “The madrasas at least teach people something and, ultimately, you are hoping they will find a job as a mosque mullah, that’s all,” he said. “They are not going to be scholars.”)

Not far from Binori Town was one of Pakistan’s largest madrasas, the Jamia Binuria Alamiya. Its principal, Mufti Muhamad Naeem, could watch all his students from the three closed-circuit televisions in his office, changing channels to view different halls or classrooms. He had 5,000 students, 3,000 of whom lived on campus. About 100 were foreigners from America, Europe, and the Persian Gulf, as well as Indonesia and Africa. He explained that there had once been white students from North America, but their presence had created problems he did not specify. He adduced a Canadian of Pakistani lineage named Imtiaz, who had been at the madrasa with his wife and 18-year-old son for five years. “Outside you have drugs, sex, and alcohol readily available,” Imtiaz told me. “Thirteen-year-old girls have sex. We feared that by the time our son was 13 years old, he would be lost. Here, boys can be natural without being forced to have a girlfriend.” Imtiaz asserted that “if criminals see the deeds of Muslims, they will be Muslims too. They will become connected to Allah and leave alcohol and murdering.”

Imtiaz took me to meet a fellow student, Farhun Mughal, from Brooklyn. The 21-year-old had spent a semester at New York University, but he decided he wanted to learn more about Islam. He told me his parents had supported his decision. His vacation was approaching, and he was excited to see his family in New York. His roommate, Afzam, was from Long Island, which he called Strong Island. They had come together in January 2004. Mughal hoped to return to the United States to teach. He and Afzam had chosen this madrasa because it had many foreign students and treated them well. Foreign students like Mughal had to pay $50 a month and got larger rooms than their local classmates, as well as air conditioning.

THE MAN BEHIND the post-9/11 attempts to reform madrasas was Moinuddin Haider, a former army commander who was appointed minister of interior by Musharraf in 1999 and remained until 2002; in 2001, in what was believed to be retaliation for Haider’s efforts to curb radicalism, his brother was assassinated. I met him in his home in the posh Defense Housing Authority section of Karachi. “We had religious extremism because of the Soviet invasion,” he said. “Jihad movements were also a legacy of the Afghan war. Our western border with Afghanistan had lost its sanctity. We had 3.5 million Afghan refugees, and they had people amongst them who believed in jihad and liberating Afghanistan with American patronage and training. Some Pakistani madrasas followed suit. These are very visible consequences of the Soviet invasion and the American proxy war.

“With hindsight,” he added, “we went too far and we failed to foresee the effects of this policy. The Pakistani internal scene was severely disturbed. Those from the Afghan war looked for new fields for adventure.” Now, Haider said, the Pakistani government was seeking to re-create Pakistan as a moderate country and “to cut down armies of holy warriors. We have tried to de-weaponize society—we banned many groups.” During his own tenure, he had sought to register the madrasas, giving them forms with questions such as who funded them and what school of Islam they taught. But even that provoked an angry response, he said, and the initiative was never implemented.

“Musharraf is pursuing a strong policy against religious extremists to make Pakistan a civilized state,” Haider said. “He is sincere in controlling religious extremism in Pakistan.” More than 300 members of Pakistan’s security forces had lost their lives pursuing members of Al Qaeda and the Taliban, he noted, and Pakistan had apprehended hundreds of wanted extremists. He complained that “the world is not concerned with sectarian killings, which is our largest problem. They are only concerned with what threatens them.”

Perhaps the only person I met in Pakistan who didn’t seem afraid of either the extremists or the “agencies” was Ardeshir Cowasjee. A former shipping operator whose fleet of five had been nationalized by the Pakistani government, he was a member of the tiny Zoroastrian sect that still survives on the subcontinent. In his 80s, he had become an acerbic commentator on Pakistani culture and politics, appearing on television and writing for the newspaper Dawn. I had seen him on television confronting a politician whose party had threatened to kill him, cut him into small pieces, and throw them into the Lyari River. Cowasjee called him “garbage,” much to the delight of Pakistani viewers.

I met him in his home, where he kept a rare collection of works by Dali, Picasso, Manet, and Rodin. He too lamented the dominance of religion in Pakistani life. “Islam was not on Jinnah’s program,” he told me. “Jinnah categorically stated that religion is not the business of the state and in no way will this country be ruled by priests with a divine vision. You can’t be more clear than this.” But, he said, “it is extremely difficult to fight ignorance, and the majority of the people are ignorant or bigoted. It is difficult to fight beliefs.” Cowasjee recounted a favorite story of his, about a visit by Singapore’s leader Lee Kuan Yew to Pakistan. Lee was asked if he had any advice for Pakistan’s dealings with extremists. “It is very difficult,” he had been quoted as saying. “These people believe in the afterlife.”

Cowasjee did not expect Musharraf to succeed. “Whatever Musharraf does now, it will be coming down,” he said. “But he’s at the top, and he would like to stay there as long as possible.” I asked what he expected to happen to Pakistan. “You cannot fight ignorance,” he said. “This country is important for what? Its nuisance value?” So what did he foresee? I pressed. “Doom,” he smiled.