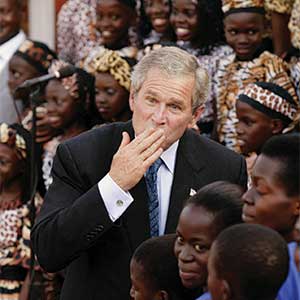

Photo: Brooks Kraft/Corbis

In February, with his domestic approval ratings at historic lows and America’s global reputation in tatters, George W. Bush set off to one place he thought he could still feel the love. On a goodwill tour of five African nations, including Rwanda, Benin, and Ghana, the president touted American aid they have received on his watch. “I’m here to really confirm to the people of Benin and the people on the continent of Africa that the United States is committed to helping improve people’s lives,” he announced during his first stop. Visiting a hospital in Tanzania, he declared the US-funded programs “God’s work.”

The White House has made much of its assistance to poor nations, especially in Africa, and in some regards aid has indeed been a highlight of the Bush administration. The President’s Emergency Plan for aids Relief (pepfar), an unprecedented commitment to battle the disease, has given 1.7 million poor people access to lifesaving antiretroviral drugs. And although America still gives less than other developed countries relative to the size of its economy, Bush has sought more foreign aid than his predecessor—$20.3 billion in 2008 compared to an inflation-adjusted $18.2 billion under President Clinton in 2000.

On the downside, as with so many of this administration’s initiatives, experts say arrogant leadership, ideological pandering, and mismanagement have marred the aid efforts. As of June 2008, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (mcc), a signature Bush anti-poverty effort, had dispensed just $235 million of the more than $6 billion Congress has made available over five years. And while pepfar has done wonders for aids treatment, it has missed the boat on prevention by insisting on moralistic rather than epidemiological strategies—until recently, one-third of its prevention funding, totaling hundreds of millions of dollars, was squandered on premarital abstinence programs that research shows don’t work. The third key Bush initiative, a large-scale effort to streamline the delivery of US foreign aid, is collapsing entirely.

George Bush paid scant attention to the subject during his 2000 run for president, but his attitude changed dramatically after 9/11—the White House, several Bush advisers told me, decided that combating poverty in potential trouble spots would reduce the risk of failed states and prevent the rise of terror havens like Afghanistan. In his landmark 2002 National Security Strategy, Bush enshrined assistance as a tool to further democracy, stating that America would “use our foreign aid to promote freedom and support those who struggle non-violently for it.” National-security types embraced the message, and then-treasury secretary Paul O’Neill embarked on a world tour with Bono, the U2 singer and global-aid poster boy, to bring attention to his boss’ humanitarianism. Joining the pep rally were conservative leaders like Kansas Sen. Sam Brownback and then-Senate majority leader Bill Frist, who traveled to Africa and returned determined to combat malaria, aids, and other calamities.

Consistent with the theory that generosity deters terrorism, Bush has funneled ever more foreign aid through the military, which has increasingly taken on humanitarian roles once left to the State Department. From 2002 to 2005, the Pentagon’s share of foreign-assistance funds quadrupled, and it now controls 22 percent of US aid. That’s worrisome, says Stewart Patrick, an expert on the Pentagon’s aid efforts at the Council on Foreign Relations. “You risk having the entire effort be driven by what the military would like to see,” he says. “Aid priorities will be out of whack since it won’t be focusing anymore on the neediest countries.” Over the past six years, for instance, America has given more than $10 billion to Pakistan, a key military ally—but the vast majority of that money, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, has gone to Pakistan’s army rather than its poor.

On the civilian front, the smart strategy would have been to consult closely with global charities and build on the expertise of career officials at the United States Agency for International Development (usaid). Instead, “the administration has responded to each new global challenge by creating new ad hoc institutional arrangements alongside the old ones,” Lael Brainard, an international aid expert at the Brookings Institution, told a House subcommittee in January. In 2004, the White House launched the mcc, an inscrutable hierarchy that rarely consulted with aid organizations, and for years left vacant the seats on its board set aside for ngo reps. pepfar, established by Congress the previous year with a $15 billion commitment, was similarly mishandled—its administrators simply bypassed usaid, which was all set up for fieldwork. “We had positions in 80 countries around the world,” says a senior usaid staffer, laughing wryly. “So they create a whole new bureaucracy.”

To run his aids initiative, Bush tapped former Eli Lilly ceo Randall Tobias, who turned out to be oblivious to his own staff’s on-the-ground experience. “We’d be at meetings, go around the table, and someone would mention, ‘I’ve just been in Ghana,’ and Tobias would say, ‘Yes, next,'” the usaid staffer recalls. “He didn’t care.”

To its credit, pepfar has revolutionized aids treatment in Africa. The international aid community had previously focused on slowing hiv‘s spread, since actually treating aids was too costly to fathom. But American generosity has changed all that. At press time, Congress was debating whether to give pepfar another $50 billion, bringing the 10-year total to nearly $69 billion.

When it comes to prevention, however, the White House has ensured that the aids program is governed by a counterproductive moral standard. Recipient nations and groups cannot use the money to support needle exchanges and other proven strategies. In Uganda, where 1 in 28 adults is hiv-positive, the US dictates have forced groups such as Population Services International to scale back condom distribution, contributing to a critical shortage by 2005. Working with prostitutes and their clients, another key prevention strategy, is also off the table. Worse, the groups can’t even use their own money for such efforts. pepfar recipients must in fact take an anti-prostitution pledge. “It says you’re not allowed to do anything that recognizes commercial sex as a legitimate occupation, or that works to promote the rights of sex workers,” says Elizabeth Pisani, an epidemiologist who has worked with prostitutes on aids prevention. “It scares people off even taking sex workers on as a population to work with.”

the millennium Challenge Corporation, conceived to support poor nations that govern justly and rein in corruption, appears to be governed by a different conservative ideology: trickle-down economics. And while economic development deserves a place in the mix, the mcc‘s grants to date have gone overwhelmingly to business interests—an equity fund in Georgia, business centers in Madagascar, a large construction project in Benin—rather than to projects that help the poor directly. By the organization’s own reckoning, education and health programs receive a paltry 5 percent of the total.

At the start, mcc officials were clueless about how to plan and execute a foreign aid project, says Jim Fox, a longtime aid expert who works on projects for the organization. According to a 2007 Government Accountability Office report, for example, the mcc claimed its five-year, $65.7 million road building and maintenance project would have a “transformative impact” on the archipelago nation of Vanuatu, benefiting 65,000 rural poor, and boosting incomes 37 percent per capita by 2015. But when gao bean counters reworked the mcc‘s fuzzy math, they calculated that actual gains per capita would be less than 5 percent—it was also unclear, the analysts said, how the subsistence farmers who make up four-fifths of the population stood to gain. “They just couldn’t get any results to show what the money went for,” comments one congressional staffer.

The administration’s broader overhaul, an attempt to streamline the delivery of foreign aid by merging usaid duties into the State Department, hasn’t fared any better. That task also fell to Tobias, whom Bush promoted in 2006 to head usaid. Sources within the agency say Tobias merely presided over a shift from one opaque, convoluted system to another, the key difference being that decisions once delegated to hundreds of field representatives were now being made behind closed doors in Washington. “When you could and should have listened to Congress and experts in the field, you instead charged ahead, making drastic changes under a shroud of secrecy,” the late Rep. Tom Lantos scolded Tobias in a hearing last year.

Aid experts at the Center for Global Development, a Washington think tank, have also criticized the overhaul process, noting that Tobias’ team generally didn’t even bother asking recipient nations what they needed from the United States. In any case, Tobias’ reign at usaid was cut short by his abrupt resignation in April 2007—it turned out the man who’d been promoting abstinence around the globe was a client of the infamous DC Madam.

The administration’s false starts have had serious repercussions, draining money from more-established aid initiatives. In its current budget request, the White House has cut more than $300 million from efforts to help the very poorest, including child survival programs in Africa. It has also slashed commitments to multilateral organizations like the African Development Bank, which gives loans and other aid to struggling African states. Also under Bush, staff at usaid, once the government’s largest repository of foreign aid experience, has been downsized by more than one-third. “We have all this money tied up in mcc, and we can’t even respond to other humanitarian disasters,” laments one congressional source.

Despite its failings, the Bush White House has at least put foreign assistance on the radar. “It’s unprecedented, this US public interest in aid,” says Paul Zeitz, executive director of the Global aids Alliance. “We need to take it from here.”

While John McCain has said little on the subject, Barack Obama has suggested doubling foreign aid by 2012. “I know that many Americans are skeptical about the value of foreign aid,” he told the Chicago Council on Global Affairs last year. “Fifty billion dollars a year in foreign aid—which is less than one-half of one percent of our gdp—doesn’t sound as costly when you consider that last year, the Pentagon spent nearly double that amount in Iraq alone.”

Such a commitment, if properly managed, could go far to heal America’s reputation. Several prominent aid experts have even proposed a new Cabinet-level position in charge of coordinating global assistance. “You’d have someone putting together all the strands, and they’d have a seat at the table,” Zeitz comments. “It would also get the US back into graces with the world.”