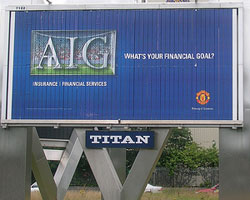

Documents released today by a congressional committee investigating the collapse of insurance giant American International Group (AIG) paint a picture of a company that sought to conceal the scope of its risky investments, despite warnings from regulators, auditors, and even its own employees that its financial disclosures were insufficient.

According to a letter (PDF) released Tuesday by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, which held a hearing on the firm’s downfall, federal regulators warned AIG executives of a “material weakness” in the company’s books five months before the insurance giant had to be rescued by an $85 billion government bailout. The federal Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) wrote AIG on March 10, 2008 that its asset valuations “lacked the accuracy and granularity necessary to understand the impact… on AIG’s accounting and financial reporting.”

AIG’s auditor, Pricewaterhouse Cooper (PWC), also warned the insurance giant about its books. Oversight committee chairman Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) pointed to minutes (PDF) from an AIG audit committee meeting in March indicating the board was told that the “root cause” of AIG’s problems was internal auditors’ lack of “appropriate access” to the Financial Products division—the very division whose massive losses eventually necessitated the $85 billion government bailout.

And even AIG’s own employees warned the company that it had no way of knowing how much risk it was exposed to. In a letter (PDF) to the committee, Joseph St. Denis, the firm’s former vice president for accounting policy in AIG’s Financial Products division, accused AIG executives of stymieing his attempts to make sure the company was properly reporting the liabilities stemming from its involvement in risky financial products, including the $62 billion credit derivative swap (CDS) market. St. Denis, who worked as a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforcement official before joining AIG, said Joseph Cassano, the head of the division, “took actions that I believed were intended to prevent me from performing the job duties for which I was hired.”

Lynn Turner, a former chief accountant for the SEC who testified at the hearing, said he didn’t see how AIG’s financial disclosures could possibly be consistent with its exposure. “When you’ve got that sort of exposure, you owe it to me as an investor [to disclose it]. That’s the disclosure I cannot find in these filings…. There’s a question there as to why we didn’t get that.”

In light of the evidence, a bipartisan chorus of lawmakers was quick to condemn the former AIG CEOs who had been asked to testify. “Quite frankly, based on a lot of the decisions you made, you deserved to fail,” Rep. Tom Davis, the committee’s ranking Republican, told Martin Sullivan, the doomed insurance company’s CEO until June 2008. Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-N.Y.), was just as harsh, telling the AIG execs that they had “cost my constituents and the taxpayers of this country $85 billion and run into the ground one of the most respected insurance companies in the history of our country” by “just gambling billions, possibly trillions of dollars.”

Sullivan and Robert Willumstad, who served as AIG’s chairman and CEO from June until mid-September 2008, blamed obscure accounting rules and actions taken before their time at the firm’s helm for the company’s collapse. The buck-passing was mutual. While AIG’s longest-serving chief executive, Maurice “Hank” Greenberg, was unable to attend the hearing due to illness, he took care to attack Sullivan and Willumstad (although not by name) in his written testimony (PDF).

Tuesday’s hearing was the second in a series of five scheduled to investigate the ongoing financial crisis, and it bore many similarities to Monday’s hearing, which investigated the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Bothers. Like Lehman’s CEO Richard Fuld Jr., who testified Monday, Sullivan and Willumstad spoke of a financial “tsunami” that could not have been anticipated and a “crisis of confidence” that took everyone by surprise. “The AIG CEOs are like the Lehman CEO in one other key respect,” Waxman said. “In each case, they refuse to accept any blame for what happened to their companies.”

But while there was bipartisan agreement among committee members that the former AIG CEOs deserved much of the blame for the firm’s near-collapse, under the surface unity a bitter partisan battle over the causes of the crisis was stewing. Republicans tend to place a lot of the blame for the current crisis on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that owned or guaranteed a huge percentage of America’s home loans. Rep. John Mica (R-Fla.) called Fannie Mae the “core perpetrator of all this.” The GOP is frustrated that Waxman has not yet scheduled hearings to investigate Fannie and Freddie’s role in the crisis, although the chairman promised on Tuesday that such a hearing would be forthcoming.

So far denied a separate hearing on Fannie and Freddie, Republicans decided to ask questions about the mortgage giants anyway. But their line of questioning didn’t get far with the former AIG execs. Asked by Davis if they saw any connection between AIG’s collapse and Fannie and Freddie’s problems, both Sullivan and Willumstad gave answers that amounted to long versions of “no.”

Members of the GOP don’t think Fannie and Freddie alone caused the crisis. They also blame an accounting rule called “mark-to-market” or “fair value” accounting, which requires that companies list assets in their books at their real market value, whether or not they have any plans to sell the assets and actually realize a profit or loss. In this, the GOP has CEOs on their side: Sullivan, Willumstad, and Greenberg all claimed fair value accounting contributed to AIG’s downfall by causing ratings agency downgrades and, subsequently, a downward spiral in the company’s stock value.

Turner, the former SEC accountant, defended mark-to-market in a section of his written testimony titled “Don’t Shoot the Messenger,” arguing that simply changing disclosure rules would not have changed the fact that the market for mortgage-backed securities has essentially dried up. Rep. Maloney accused Sullivan and Willumstad of “blam[ing] accountants for saying a product has no value when no one wants to buy it.”

In contrast to the Republicans’ fixation on Fannie, Freddie, and fair value accounting, the Democrats have focused on credit derivative swaps as the salient issue in this crisis. Credit derivative swaps are unregulated bets on whether or not companies will default on debt. They were originally designed as a form of insurance, or hedging, but now only a small percentage of the $62 trillion swap market is backed by collateral. (Since $62 trillion is close to the combined annual economic output of the entire world, the lack of collateral is understandable). AIG’s financial products division had sold billions of dollars in swaps before 2005, when they halted the practice. But when AIG’s credit ratings were lowered in 2008, the company had to post enormous amounts of collateral for credit default swaps that it had previously held with low collateral or collateral-free. The need to raise this collateral soon led to the government bailout.

Eric Dinallo, the Insurance Superintendent for New York State, argued before the committee that the credit default swap market has to be regulated, calling it a “major contributor to the emerging financial crisis.” Asked if the unregulated swap market “could bring down our entire economy,” Dinallo said, “Well, we’ll see.” In the meantime, SEC Chairman Christopher Cox has already asked for the power to regulate the market. It was a testimony to the damage the credit derivative swap market has wrought that even the former AIG CEOs have come around to the idea of regulating it. Both Sullivan and Willumstad said under questioning that they would prefer if the market were regulated. “With benefit of hindsight, if there is good regulation that could be put in place… I would support that,” Sullivan said.

Photo by flickr user Gene Hunt used under a Creative Commons license.