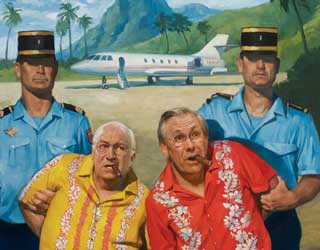

Illustration: Roberto Parada

Just weeks before the 2004 presidential election, Donald Rumsfeld, then secretary of defense, appeared at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York City. After the secretary finished, with customary panache, assessing the state of the war on terrorism (“Have there been setbacks in Afghanistan and Iraq? You bet”), a young man in a business suit asked politely, “Mr. Secretary, you have a very impressive career both within… and outside the government sector. As such a credible leader, could you please explain to us what your definition of the word ‘accountability’ is?”

Rumsfeld seemed nonplussed. “Capability?” he asked. “Accountability,” the young man repeated politely, yet firmly. “Oh no, I don’t know that I can,” the secretary said. He cast out a few platitudes—”checks and balances,” “gray areas,” “individuals who have responsibilities”—only to find his stride by turning to Pentagon personnel metrics. He concluded that “You need to put in place a series of things that hold people reasonably accountable for their actions, and people, I think, expect that.”

Today, with Rumsfeld and his former boss on their way to the judgment of history, the question of accountability looms large. From liberals fantasizing about Dick Cheney in handcuffs, to cia officials taking out insurance against prosecution, many are wondering: Will there be redress for the crimes of the Bush administration—and if so, what form should it take?

The list of potential legal breaches is, of course, enormous; by one count, the administration has broken 269 laws, both domestic and international. It begins with illegal wiretapping and surveillance (which in the view of many experts violated the Fourth Amendment, the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, for starters), the politicization of the Justice Department and the firing of nine US attorneys, and numerous instances of obstruction of justice—from the destruction of cia interrogation tapes to the willful misleading of Congress and the public. Perhaps the paramount charge that legal experts have zeroed in on is the state-approved torture that violated not just the Geneva Conventions and the UN Convention Against Torture but also the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the 1996 War Crimes Act, which prohibits humiliating and degrading treatment and other “outrages upon personal dignity.”

With these abuses in mind, lawyers, policymakers, and others have identified three models from which to fashion a response to the Bush era. In decreasing order of opprobrium, the choices are impeachment, prosecution, and investigative commission.

Impeachment, according tothe consensus emerging in Washington and among a wide spectrum of lawyers and human rights advocates, seems both unlikely and undesirable. Though it has reared its head periodically over the past eight years—most notably with Rep. Dennis Kucinich’s articles of impeachment against Bush and Cheney—Democratic leaders have declared the option “off the table.” And at this point, it’s a bit moot.

The idea of prosecution has fared only slightly better. In Italy, 26 Americans—including cia agents, a military attaché, and several diplomats—face charges in conjunction with the rendition of radical cleric Abu Omar to Egypt. Human rights organizations, notably the Center for Constitutional Rights, have teamed up with partners in Germany and France to pursue charges against Rumsfeld for violating the Convention Against Torture, though so far to little effect. The possibility of other cases has been raised, most recently in British barrister Philippe Sands’ warning that Congress should investigate the torture question, for “if the United States doesn’t address this, other countries will.” (See opposite page.)

More significantly, there have also been rumblings about prosecution here at home. Attorney General Michael Mukasey has already appointed a special prosecutor to look into the Justice Department firings; potential targets include four top doj officials as well as Karl Rove and Harriet Miers. In June, 56 congressional Democrats signed a letter to Mukasey seeking an investigation into detainee abuses with an eye toward violations of “federal criminal laws.” Then, after a September conference on the crimes of the Bush administration sponsored by the Massachusetts School of Law at Andover, attendees launched a committee to seek the prosecution of the president, chaired by the school’s dean, Lawrence Velvel. Also in September, Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wis.) introduced the Executive Branch Accountability Act of 2008, which calls for the new president to “investigate Bush/Cheney administration officials’ alleged crimes and hold them accountable for any illegal acts.” Baldwin’s plan would require Congress to appoint a special prosecutor to consider the possibility of criminal charges—a model whose historical precedents Americans are only too familiar with.

Still, when I asked a range of legal and political experts about the prosecution option, few seemed to consider it worthwhile—at least at this point. “We need some sort of accountability,” Georgetown law professor Marty Lederman told me, “but it won’t necessarily be by prosecutions.” The reasons are practical as well as philosophical. Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz explained that “the real question is whether investigating one’s political opponents poses too great a risk of criminalizing policy differences—especially when these differences are highly emotional and contentious.” Others, including nyu law professor and former aclu president Norman Dorsen, who chaired two investigative commissions for the Ford and Clinton administrations, warn of the dangers of appearing vengeful, or even creating sympathy for those under scrutiny. After all, some argue, John Yoo, Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, and the lot are already persona non grata; though they’ll likely do fine in the private sector or academia, their reputations are indelibly tarnished and their political careers effectively over.

Perhaps the biggest question, though, is one of political will given that Americans, it seems, really aren’t that upset about what has happened. A recent University of Maryland poll found that tolerance for torture of suspected terrorists has actually risen in recent years, from 36 percent in 2006 to 44 percent last June.

Barack Obama’s campaign message reinforced this reluctance to prosecute. In essence, he has promised to create a national unity government, a notion that doesn’t square with criminally charging one’s predecessors. As Obama put it last April, “I would not want my first term consumed by what was perceived on the part of the Republicans as a partisan witch hunt, because I think we’ve got too many problems we’ve got to solve.” Obama’s advisers, too, have let it be known that prosecutions are not on the agenda except for “egregious crimes,” a term that seems purposely vague. Only Joe Biden, perhaps straying from his talking points (again), has seemed open to the possibility. “If there has been a basis upon which you can pursue someone for a criminal violation, they will be pursued,” he said last fall, “not out of vengeance, not out of retribution—out of the need to preserve the notion that no one, no attorney general, no president, no one is above the law.”

But it is not just political caution that stands in the way of prosecution. It is also the fact that torture and other alleged crimes were sanctioned by legal advice within the administration and, in some cases, by Congress. The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel has the authority to interpret the law for the executive; these interpretations—including the “torture memos”—are considered binding until they are reversed or disavowed.

In addition, the Military Commissions Act of 2006 limited the abuses that can be prosecuted under the War Crimes Act to only the most extreme violations of the Geneva Conventions (thus codifying the distinction between “torture” and “degrading treatment”); the changes were made retroactive to 1997, creating what Garth Meintjes, a noted authority on transitional justice and amnesties, has called “quasi amnesties.” These changes are one reason why the Senate armed services and judiciary committees, in their hearings on torture last summer, seemed to focus on proving perjury as much as substantive violations of law.

With impeachment out of the picture and prosecution receding as a possibility, attention has turned to an investigative commission along the lines of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that followed the end of apartheid in South Africa, the 1967 Kerner Commission on race, or the 9/11 Commission; the best model may be the Church Committee, Congress’ response to the 1970s revelations on Watergate, cia destabilization programs abroad, and surveillance of Americans. (The Church hearings led to creation of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court.) Perhaps recognizing that his impeachment bill is past its sell-by date, Kucinich has cottoned to the commission idea, announcing in September that he was looking to introduce legislation to launch just such a body.

As Walter Lippmann once wrote, congressional commissions can turn into a free-for-all as politicians, “starved of their legitimate food for thought, go on a wild and feverish manhunt, and do not stop at cannibalism.” Accordingly, some favor the idea of an independent commission, run by someone of the stature of Plamegate prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald or former New York US Attorney Mary Jo White, in the hope that this format would be less politically charged. The goal would be to prove Lippmann wrong and establish the facts in a reliable, nonpartisan fashion—to create an authoritative narrative that the nation could share.

But what kind of commission makes all the difference. Truth and reconciliation commissions, which the United States has never had at the federal level, are for healing. Watergate-style commissions bear the prospect of condemnation, exposure, and punishment. Then there is the question of just what is to be found: Much of what happened in the run-up to the war, the torture scandal, or the National Security Agency wiretaps has already been documented in news articles, books, and congressional probes; what is missing, though, is the full story about who knew what and when. Perhaps a commission could get members of the Bush administration to reveal these details. Perhaps there are other skeletons to be unearthed. The best hope, Meintjes ruefully acknowledges, is for a “negotiated truth” along the lines of the 9/11 Commission. As attorney Scott Horton has pointed out in Harper’s, “Investigative commissions can provide truth…but they cannot provide justice.”

Yet it’s also true that once a commission begins, it is hard to control just where it will go. Although many who embrace the idea of a commission have disavowed prosecution, once the facts are out, criminal charges may yet follow. If prosecution looms as a possibility, testimony may be difficult to obtain. But if immunity is offered—a common element in truth and reconciliation commissions—prosecutions may prove problematic.

To be sure, any commission would be time-consuming and could distract the new administration from the urgent work of addressing the war in Iraq and the financial crisis. And there’s the problem of potential complicity among those charged with the investigation. Members of Congress who voted for war, for example, would rather not revisit that moment; ditto those who were briefed on the wiretaps and the cia interrogation techniques.

Yet the downside of not addressing crimes of power is immense. It creates a space for lingering suspicion that the new president might want to keep some of the excessive authority Bush carved out for himself. What’s more, signaling a new way forward in the matter of torture could go a long way toward reestablishing the government’s credibility at home and abroad. One possibility, suggests Dorsen, is for Congress or a blue-ribbon citizens’ commission to hold investigative hearings; only if crimes are revealed would the attorney general consider (very carefully) what the consequences of prosecution would be.

Whatever form it takes, the accounting will not be easy. As one close observer has put it, “Who would want the job of cleaning the Augean stables anyway?” Congress may not be able to redirect the rivers as Hercules did to wash out the accumulated filth, but it can go a long way in that direction. Accountability is a worthy goal even if incomplete. To borrow a phrase from Chile’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the best we can hope for is “all the truth and as much justice as possible.”