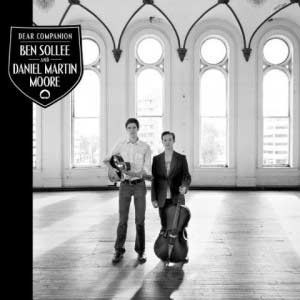

Photo by Liz Linder

Onstage at the Telluride Bluegrass Festival, Ben Sollee paints an unassuming portrait. He’s small in stature, with the baby face of a teenager—despite being in his twenties and married, with a son. He sits on a low stool with only his cello as a companion. But as soon as he starts singing, his voice, silky with a touch of smokiness, fills the field where we sit and slides up the sheer peaks behind us, quieting the chatter of the crowd until all eyes are upon him.

A Kentucky native—his father a guitarist and grandfather a fiddler—Sollee was raised amid the musical traditions and culture of Appalachia. He studied classical cello and then teamed up with three musicians, including the legendary banjo player Bela Fleck, to form The Sparrow Quartet in 2005. Two years later, NPR’s Morning Edition named him one of the “Top 10 Great Unknown Artists of the Year.”

Sollee’s original, rhythmic plucking, bluesy angelic vocals and unencumbered lyrics make for mellow listening. But his songs often carry the weight of incendiary protest. His latest album, Dear Companion, a collaboration with guitarist/singer Daniel Martin Moore, aspires to alert people to the devastating practice of mountaintop-removal coal mining. (For more on this, see “Razing Appalachia.”) Jim James of My Morning Jacket signed on as a producer, and the artists plan to donate all of the proceeds to iLovemountains.org, a nonprofit that aims to put an end to mountaintop removal.

But you can admire Sollee simply for his musical innovations: A new documentary, Wooden Box, focuses on how he has set out to demystify the cello—transforming it from stuffy classical instrument to a chameleon-like accoutrement. At the show, he gave a talk about it.

Lately, he’s taken the unlikely—some might say crazy—step of touring by bicycle. He totes his cello by way of an Xtracycle—one of those extra-long bikes surfers use to haul their sticks to the beach. “First bicycle tour through Appalachia—maybe not the best idea I’ve ever had,” Sollee says with a laugh as we sit in the shade after his set. “But something clicked, and I was like wow! This is beautiful.” He’s now embarking on a national bicycle tour.

Mother Jones: Whatever possessed you to tour by bicycle with a cello?

Ben Sollee: I saw an advertisement for an Xtracycle, and I was like, “I could actually ride with my cello on that!” So we tried out a tour to Bonnaroo. There was something very human about it, and the fact that I needed a lot from the community—not only from the venues, but places to stay near the venues and support from bike shops. It’s not always easy to convince managers and booking agents: Their interest really is in raising your economic wealth up, and you’re like, “I want to go to this place where there’s this really cool bike shop.” You have to really be in areas where the towns are close enough together and vibrant enough to put on small, central shows. Really, what you are talking about is limitations. Limitation number one is the bicycle, because you can only go so far so fast. And it becomes this really beautiful limitation because you get to justify playing in all these small communities along the road that you would never be able to justify stopping in from the perspective of a nationally touring artist.

MJ: You studied classical, which is largely bowing, but I notice you do an awful lot of plucking up there.

BS: Playing with a vocalist or a banjo or a fiddle player—they all require different things of you as a cellist, especially within the vernacular of the music. So I would just pick up all these other techniques that made sense for the cello and just develop them. There’s nothing original there; it’s all stolen from other instruments. It’s just that the cello really lends itself to having those techniques transposed to it.

MJ: In “Only a Song,” you write, This is only a song, it can’t change the world. Given your own activism, how do you view music as a tool to affect change?

BS: I think music can serve as a point of conversation, just like any other artistic medium. But music has a special way of making its way into people’s personal lives. As opposed to just viewing a piece of art and being affected there, a song can be carried with people, whether they sing it or listen to it in all the time. But I don’t think any protest song was ever written to be a protest song. Historically, songs have found their place in movements because the audience makes it that way. The artist writes in a really small world, and people propagate it. It’s a lot like the idea of phenomenology that Shepard Fairey preaches about with all his images. It would be impossible for me to write a song if I knew I were writing it for masses of people to be a protest song.

BS: I think music can serve as a point of conversation, just like any other artistic medium. But music has a special way of making its way into people’s personal lives. As opposed to just viewing a piece of art and being affected there, a song can be carried with people, whether they sing it or listen to it in all the time. But I don’t think any protest song was ever written to be a protest song. Historically, songs have found their place in movements because the audience makes it that way. The artist writes in a really small world, and people propagate it. It’s a lot like the idea of phenomenology that Shepard Fairey preaches about with all his images. It would be impossible for me to write a song if I knew I were writing it for masses of people to be a protest song.

MJ: What are some of the most memorable responses to your effort to draw attention to mountaintop removal?

BS: There’s a fellow on Kayford Mountain—they call him “the keeper of mountains“—Larry Gibson. He’s been fighting this stuff for about 25 years. He’s got a small piece of land that he’s protected, but they’ve ended up mountaintop-removal mining all around it. So his water table’s dropped out. He’s huddled up there on the mountain; the electricity is shaky at best. He’s constantly getting harassed by coal miners and even police officials. You get a lot of people coming through there, and I played at a festival and he was there. And he said, “You know what, your music gives me hope.” That was a really deep response for me. That meant a lot from somebody who has been struggling for so long.

For the music, I’ve had really strong good reactions, but with the message, sometimes people are like, “What’s the big deal?” People a lot of times point and say, “Well that’s just the way it is there.” Well that’s not the way it is here. We’re sitting in Telluride, Colorado, where all kinds of stuff was mined. But it was never worth so much as to actually tear down the mountain. How do you value an untouched mountain? I think that’s something that lawmakers and environmentalists are working really hard to try to figure out. Because how can you put a value sign on not only the actual physical mountain, but also the trees above it, the fact that it wicks all this water through, and all the culture that surrounds it?

MJ: What’s the best part about playing at Telluride?

BS: Oh, wow. Probably the community. It’s been going on for a long time, so it’s very established, they’ve got all the intricacies figured out. So at this point they are just here to collect. And they gather and they love the music and put it out. It seems like there is such a sense of awareness about issues, about the artists. People love telling stories to each other.

Below: A couple clips of Sollee in action.

Click here for more Music Monday features from Mother Jones.