Photo courtesy of Flickr user <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/dvids/" target="blank">DVIDSHUB</a>.

A Western official knowledgeable about Afghanistan’s private security scene pointed me to this letter to the editor from the Afghan ambassador to the US, Said Jawad, that ran in the New York Times earlier this week. Jawad is responding to a recent Dexter Filkins piece about Matiullah Khan, a provincial powerbroker in Oruzgan. Khan, once a highway patrol commander, heads a paramilitary force said to be 2,000 men strong, which protects NATO convoys on a particularly dangerous stretch of road between Tirin Kowt and Kandahar. His men also take part in operations with US Special Forces soldiers. It’s very lucrative work. He brings in an estimated $2.5 million per month.

The gist of Filkins’ story—which is well worth reading in its entirety—is that while Matiullah’s services may be helpful in the short-term, empowering him and other local strongmen (there are many) come at the cost of NATO’s long-term objectives. For instance, as Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.) pointed out this week, building up a capable national army and police force is made even more difficult by the fact that local security operations, which pay better, are recruiting directly from the ranks of the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police. There’s also the fact that Matiullah may be engaging in criminal activity on the side, conniving “with both drug smugglers and Taliban insurgents”—reports of which military commanders apparently ignore in order to justify relying on his services.

The questions Filkins raises in his story are legitimate and troubling, but his characterization of Matiullah rankled the Afghan ambassador. Jawad writes that the story “left the impression that an effective founder of a private security firm is somehow a ‘semiofficial warlord,’ undermining government institutions in Oruzgan Province.”

The Taliban regularly attack supply caravans. NATO cannot secure the safety of its own transports, and because the Afghan Army is deployed in the battle with the Taliban, adequate police officers cannot protect remote highways. Yet risk-taking entrepreneurs like Matiullah Kahn have filled this security vacuum.

First, I’d say Jawad’s impression was precisely the one that Filkins was trying to leave. Second, I actually think Filkins was being somewhat charitable when he referred to Matiullah as a “semi-official warlord.” If there’s even such thing as an “official” warlord, Matiullah is a member of the club. Also, Matiullah doesn’t run a “firm” per se. It’s basically a militia, which goes by the name Kandak Amniante Oruzgan (or Highway Police Oruzgan). What Jawad conspicously fails to mention is that Matiullah’s operation is considered illegal by the government he represents, which requires security outfits, local and international alike, to be licensed through the Ministry of Interior.

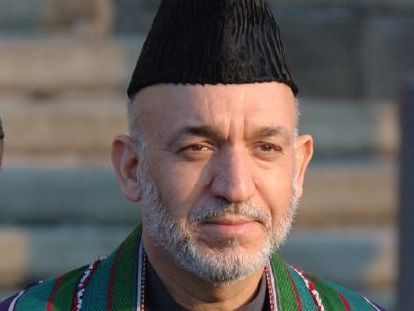

In the past, the ministry has even offered Matiullah a license and a government contract, according to Hanif Atmar, who served as Afghanistan’s Interior minister until earlier this month, when he was forced to resign by Afghan president Hamid Karzai. But Matiullah has refused to come under government control—which doesn’t bode well for any potential efforts in the future to integrate his militia into the Afghan security forces, let alone disband his private army. (And let’s not forget that in November Karzai vowed to phase out all private security operations within two years. Good luck.) “Parallel structures of government create problems for the rule of law,” Atmar told the Times.

Creating a stable society and a strong central government are, above all else, the Afghan president’s main objectives. So why would Karzai’s man in Washington go out of his way to defend a warlord—or entrepreneur, or whatever you want to call him—who is confounding these goals?