Neal Jorgensen testifies on April 28, 2010, before the House Subcommittee on Workforce Protections.

A version of this story first appeared at FairWarning.org.

Neal Jorgensen’s mistake was taking the government at its word.

In 2004, after he reported hazards at his job with a plastics recycling firm in Preston, Idaho, two things happened right away. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) cited the plant for multiple violations, and Jorgensen got fired.

It’s illegal to fire someone for blowing the whistle on safety violations, so he complained of retaliation, and an OSHA investigation backed him up. At that point, Jorgensen’s bosses could have settled his complaint for a paltry amount of back wages, but they refused. So OSHA referred his case to lawyers at the Department of Labor.

Federal law dictates what should have happened next: The secretary of labor is supposed to sue the employer. But the department’s lawyers refused. “My employer got away with firing me without any consequences,” Jorgensen, 58, told me recently.

Jorgensen’s wasn’t an isolated case. Over the past 14 years, scores of whistleblowers have seen their claims fall into a black hole because the Office of the Solicitor, Labor’s legal arm, wouldn’t go after their bosses in court—no matter that OSHA found that these workers had been illegally demoted or fired. From 1995 to 2009, according to government figures, regional solicitors filed a mere 32 whistleblower lawsuits, rejecting 279 other cases referred to them by OSHA.

These workers aren’t the only losers in all this. Current and former OSHA investigators say it’s harder for the agency to settle ongoing complaints because employers know they won’t be sued. The solicitors “want cases that are slam dunks,” said a frustrated investigator who, like several others I interviewed, spoke on condition of anonymity. “They don’t want a case that we could possibly lose…That’s just a ridiculous standard.”

Another investigator told of being laughed at when he asked a company’s lawyer to produce a document in a whistleblower case. “‘What are you going to do, take us to court?'” the lawyer asked. “And we both laughed,” the investigator said, “because the odds of the solicitor taking the case to court are slim to none.”

Representatives from the solicitor’s office would not consent to an interview, but insisted via email that the office’s record is better than how critics portray it: Beyond the 32 lawsuits filed during that 14-year period, the office reached settlements in 156 other OSHA cases, they noted; solicitors have litigated or settled about 40 percent of OSHA referrals since 1995—more than 50 percent over the past five years. “These are not numbers that should cause employers to feel comfortable engaging in safety-based retaliation,” the email reads

OSHA and the solicitor’s office are backing legislation that would let whistleblowers pursue their own retaliation complaints if government lawyers refuse to do it for them. “We are enormously frustrated when we find merit in a case and the solicitors decide not to take that forward,” said Jordan Barab, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Labor for OSHA. “We also understand that the solicitors have the same resource issues that we have, and that’s why we need a change in the law.”

But given the magnitude of its staffing problems, bulging caseloads, and investigative delays—some critics say the whistleblower program is broken and cannot be fixed by tweaks to the law.

The parent agency is itself spread so thin that, by the AFL-CIO’s estimate, its inspectors would need an average of 137 years simply to check each workplace under their jurisdiction once. Back in 1970, hoping to encourage workers to serve as extra eyes and ears, Congress wrote protections into the Occupational Safety and Health Act that make it illegal to fire, demote, or harass employees for reporting safety violations.

It seemed such a good idea that Congress began adding whistleblower protections to myriad regulatory measures—laws involving air and water quality, airline and trucking safety, even accounting fraud. The portfolio of complaints expanded rapidly to accommodate what was a largely unfunded mandate.

Today, the Whistleblower Protection Program is responsible for enforcing the anti-retaliation provisions of 17 separate laws, most of which have nothing to do with OSHA’s core mission of reducing workplace injuries and deaths. Investigator training has lagged far behind. Consider two of the most complex statutes in question—the Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment and Reform Act and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. They became law in 2000 and 2002, respectively. Yet in 2008, when the Government Accountability Office surveyed OSHA’s whistleblower investigators, one-third to one-half said that they had not received specific training in these laws.

“The resources don’t match what we say—how much we respect whistleblowers,” said Celeste Monforton, a former OSHA official who is now assistant research professor of environmental and occupational health at George Washington University.

Indeed, at an agency long saddled with austere budgets, the whistleblower program was never a priority—some critics call it an unwanted stepchild. Which means that employees anxiously awaiting the results of an investigation are typically left hanging for months.

Given the program’s chronic shortages of manpower, training, and equipment, some demoralized whistleblower staffers have become whistleblowers themselves, venting their frustrations to congressional aides and others. “We try to do the best we can, given what we have to deal with,” offers Labor’s Barab, “but we have a lot to deal with.”

Advocacy groups have weighed in on the issue as well. Calling OSHA “resource-starved even for its primary activities,” the Government Accountability Project has described protecting whistleblowers as “a mission conflict” for the agency. Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, recently charged that whistleblower protection “is not just on the back burner; it has fallen off the stove.”

The whistleblower program has its own dedicated corps of investigators, distinct from the larger force of OSHA inspectors who check job sites for health and safety compliance. Over the past decade, the number of investigators has hovered between 70 and 75, despite the new laws they’ve been asked to deal with. A whistleblower investigator can realistically handle six to eight cases at a time, OSHA says. But in several regions of the country, they average 20 or more. In one region, the average is a whopping 32 open cases—and one investigator had 69, according to data obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

At least twice in recent years, funds meant for hiring new investigators for the whistleblower program were instead used to plug the parent agency’s other shortfalls. Earlier this year, OSHA began hiring 25 new investigators in what Barab calls “the first semi-significant expansion in many, many years.”

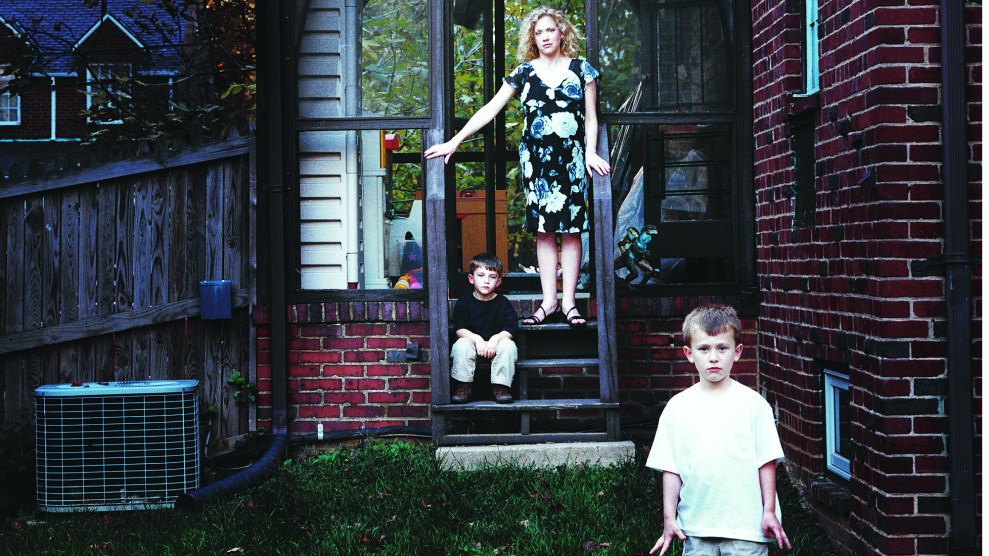

Whistleblower laws require that investigations be completed in 30 to 90 days. But from November 2009 through May 2010, the average case took 174 days to complete, according to OSHA stats. Employers can handle that delay—workers less so. “The deck is stacked against the whistleblower,” an investigator told me. “Some of them just can’t wait that long. They lose their houses. They end up getting divorced over the financial woes. And, of course, their wife doesn’t understand why they didn’t keep their fucking mouth shut and keep their job—why they had to blow the whistle in the first place.”

Pressure to keep up with heavy caseloads can also lead to a subtle bias in the employer’s favor, some investigators admitted. That’s because it’s faster and easier to dismiss a complaint than to marshal the evidence needed for a merit finding. Last year, Jason Zuckerman, a DC lawyer who represents whistleblowers, wrote a letter to OSHA officials complaining that some investigators “look for any reason they can find to dismiss a complainant’s claims. This is often done by questioning every factual assertion a complainant makes while unquestioningly accepting the employer’s justifications.”

The numbers confirm that whistleblowers fare poorly. Of some 2,000 annual complaints, about 1,600 are withdrawn or dismissed by OSHA. The remaining 20 percent, known as “merit” cases, are usually settled with the employer—relatively few result in a finding against the company.

Under the laws of some states, a whistleblower can file a wrongful termination case in court rather than trust the OSHA process. As a practical matter, though, the modest damages available in such cases make it hard to find a lawyer who will take them. Some of the newer federal laws that OSHA administers let a whistleblower appeal his case to an administrative law judge if the agency dismisses it—but the 1970 OSHA act leaves no such recourse. If a case filed under its provisions cannot be settled, or OSHA finds it lacks merit, or solicitors refuse to take it to court, the worker is out of luck.

That’s what happened to Neal Jorgensen.

In April 2004, after a fellow worker at Plastic Industries was cut by a bandsaw, Jorgensen cosigned a complaint to OSHA’s Boise office. The agency inspected the shop and issued several citations, including “serious” ones for lack of a guard on the bandsaw and inoperative safety features on other machinery.

With the plant abuzz over who had dropped the dime, suspicion quickly focused on Jorgensen. A few days after the inspection, he reported for work and was abruptly sent home. He was told that the baling machine he would have operated that day had been found in violation by OSHA and was unavailable for use. (OSHA later determined that other workers had run the baler that day.)

Jorgensen was fired the following day—allegedly for poor performance. But company managers were inconsistent about the reasons for his firing. Also, when an OSHA investigator showed a letter critical of Jorgensen to the foreman who supposedly wrote it, the man said he’d been asked to write it, and that the original had included positive statements about Jorgensen that someone removed before faxing it to OSHA. “In conclusion,” the investigators wrote, “there is a preponderance of evidence that a prima facie complaint of discrimination has been established.”

The agency calculated that Jorgensen was due a little under $3,000 in lost pay—peanuts, really. But the company balked, and OSHA referred Jorgensen’s case to the Department of Labor solicitor in Seattle. The following April, Jorgensen received a letter from the solicitor, calling the case “unsuitable for litigation” due to “insufficient evidence.”

A cruder explanation emerged at an April hearing of the House Subcommittee on Workforce Protections. Jorgensen read to the legislators from an internal solicitor’s memo discussing his case: “We believe we have an approximate 25 percent chance of success,” it read. “There are two US district Court judges in Idaho, one of whom is routinely not well disposed towards the government’s cases, and the other who can go either way.”

The Protecting America’s Workers Act, currently in committee, proposes to update provisions in the 1970 OSHA law. It would let workers appeal to an administrative judge if OSHA rejects their case or the solicitor refuses to pursue it. It would also extend the deadline for filing a retaliation complaint from 30 days to 180 days after the incident. Introduced last year by Rep. Lynn Woolsey (D-Calif.), the bill now has more than 100 cosponsors. Similar legislation is pending in the Senate. “There’s a lot of accidents that could be prevented if workers weren’t afraid to call the situation to the attention of somebody above their bosses if their bosses won’t pay attention,” Woolsey told me. “But they’re afraid for their jobs.”

Lloyd B. Chinn, a partner with Proskauer Rose LLP who specializes in defending companies in employment matters, told me that diverting cases from regional solicitors to administrative judges may simply mean routing them from one understaffed bureaucracy to another. “I’m not sure there is proof that the system doesn’t work,” Chinn said, “and if it doesn’t work, I’m not sure this fixes it.”

As things now stand, Jorgensen would not advise anyone to file a whistleblower complaint. “Absolutely not!” he said. “The way the law is written—no chance.”