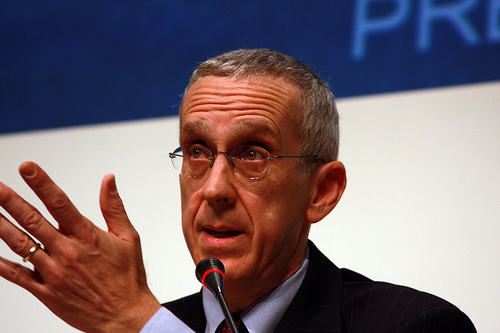

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/oxfam/5242221997/">Oxfam International</a>/Flickr

Pablo Solon, Bolivia’s ambassador to the United Nations, might be the world’s most ambitious climate negotiator. But his reputation is more notorious than renowned. In 2009, when Bolivia (with one other country) boycotted the Copenhagen Accord, Solon said his country would not support a proposal based on voluntary carbon emission reductions rather than legally binding targets. A few months later, the US denied climate aid to nations that did not support the accord, including the $3 million Bolivia requested. By the time negotiators reconvened in Cancun last December, Bolivia was the only country to oppose the proposed global deal.

While the Cancun Agreements have since been applauded as pragmatic (if modest) for focusing on country-specific targets and zeroing in on tangible mitigation efforts like combating deforestation, Bolivia has continued its unlikely campaign for stringent and binding targets. The next round of talks in Durban, South Africa is just six months away, and some pundits are arguing that mandatory targets are not only unrealistic but also akin to climate diplomacy suicide. With the existing Kyoto Protocol set to expire next year, there is no comprehensive replacement in sight. “In Durban it’s almost impossible to see a legally binding agreement,” Japanese delegate Akira Yamada told Reuters last week. (Read MoJo reporter Kate Sheppard’s analysis for more on the international negotiations.)

But Solon remains determined, because he has to. More than 40 percent of his country has been affected by desertification due to climate change, and its glaciers are disappearing at unprecedented rates, threatening the country’s long-term water supply (PDF). Before heading off to the ongoing climate summit in Bonn, Germany, Solon* talked to Mother Jones about how the Cancun Agreements set a destructive precedent for addressing climate change, why the US is the real obstructionist, and why he’s hopeful that more countries will start to see things his way.

Mother Jones: What does Bolivia want to see come out of the Durban climate summit?

Pablo Solon: The key issue is, are developing countries going to present in Bonn [reduction targets] that are higher than the ones they presented in Cancun? If we don’t reduce more, then we have done a very, very, very bad deal. I don’t see the US moving its targets. That is a very bad sign because the US is a key player in this. If the US would move, others would move. But because the US has a very low pledge, that’s a very big problem. I suspect that by Durban we will have a second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, maybe not of everybody, but at least with key players. This will be a step forward that will put more pressure on those countries that have very low pledges of emission reductions.

MJ: Even with a more ambitious target, how do you foresee that being implemented?

PS: There is a problem here. In some cases there have been concrete emission reductions. In other cases, there were just new ways of calculation that in reality didn’t mean real emission reductions. In order to stick to our commitments, Bolivia proposes developing a new compliance mechanism.

MJ: What’s that?

PS: An international court of climate justice, where when you make a commitment, you are accountable. You cannot play around with the future of other nations and of humankind as a whole, because many small island states are going to disappear beneath the water if the temperature increases and the sea level rises. The court would be like the International Court of Justice, where if you sign an agreement but you don’t comply with it, then you will be subject to a process of demand. This will be specifically a court that deals with climate change and commitments of emission reductions.

MJ: Let’s assume we can’t get countries to sign on to legally binding targets, and then Kyoto expires. What then?

PS: The problem is that if you stick to the present pledges, we are going to have a scenario where global temperatures increase by 4 degrees Celsius. That is not acceptable. If there is not huge social pressure, we are not going to be able to change the course of negotiations. We need to have pressure like we had in relation to nuclear plants in Germany or movements like the one we are seeing in Spain, where civil society really takes to the street and puts a lot of pressure on government.

MJ: How far or close are we to getting there?

PS: I would say more and more. Next month you’re going to see a new natural disaster that is because of climate change. And you will see another one. Until when? Until you have a reaction from the people. Look at nuclear energy. Five months ago, if somebody would have told you there would be a massive protest in Germany against nuclear energy, you’d have said, why? What is going to happen with relation to climate change is the same but on a much broader scale. Sooner or later, there is going to be a reaction, and the mobilization from the people is going to shift the course of these negotiations.

MJ: But by the time there is enough social pressure on governments to act, won’t certain countries already have disappeared off the map?

PS: It is possible. In the case of my country, a country that has mountains with glaciers, we have lost, already, one third of the glaciers. In the next decade we [may] lose another third of our glaciers, which will have a terrible impact on biodiversity, access to drinking water, agriculture, indigenous peoples, communities, and so on.

MJ: What do you say to other countries that don’t think a binding agreement is realistic?

PS: The problem is you cannot sign an agreement that will condemn 350,000 to die because of natural disasters that are related to climate change. Would you sign on to that? Would you be responsible for that? This is not a trade negotiation, you know? When we speak about trade we say ‘Let’s find a middle point where you win and I win.’ In climate change, we’re not negotiating markets or commodities. We’re negotiating how we are going to save humankind, life, and nature. And in that sense there is a limit. So what is it to be realistic? That only 20 percent of the world population is going to see the future at the end of this century? No. When I go to negotiate I say, ‘I have a red line. My red line is that I don’t want to see any state sitting at this table disappear.’

In the Cancun outcome, they say 2 degrees Celsius. But even the pledges that are on the table are not consistent within this scenario. So this has to end. Three degrees means how many people are going to die? How many people are going to have to migrate? One-hundred, two-hundred million? What are the consequences of that? Think what would happen if I told you, as an American, ‘Yeah, don’t worry, we’re going to find you another place to live. You know, be realistic.’

MJ: What do you see as the role of large emerging economies, which have grown significantly since Kyoto was signed? Are they doing enough?

PS: If you summarize all the pledges of the developing countries, in the low end, the developed countries are going to reduce 3 gigatons. And developing countries are going to reduce 3.8 gigatons. With their best effort, developed countries are going to reduce 3.6 gigatons and developing countries are going to reduce 5 gigatons.

All of the developing countries, without any kind of binding agreement, are already seeing what they can do. We said in Bangkok, stop saying that we’re not doing this because China, India—look at the figures. They are doing more than what you as developed countries, who have historical responsibility, are doing. We’re not saying that developing countries should not do it. We’re already doing it, and we can do even more. But it’s absolutely unfair that developed countries, that are mainly responsible, are doing so little.

*Solon was in San Francisco to receive Global Exchange’s 2011 Human Rights Award. Special thanks to John Wilner.