<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/18003921@N08/4991248948/sizes/z/in/photostream/">soksia</a>/Flickr

You—the public—once essentially owned the Sergei Prokofiev classic Peter and the Wolf. You could play it for your friends and charge admission. You could remix it with other music. You could write a book called Peter and the Wolf and Zombies. You didn’t have to worry about getting sued because the work was in the public domain.

Then, in 1994, Congress suddenly snatched Peter and the Wolf and millions of other works out of the public domain. The move was part of a deal to secure broader copyright protection for American works in foreign countries. (Not that it worked very well: As anyone who has ever been there knows, it’s not exactly hard to find DVDs of newly released Hollywood movies on the streets of Moscow.)

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Golan v. Holder, a case that addresses whether it was constitutional for Congress to remove Peter and the Wolf and other works from the public domain. The case was brought by University of Denver professor Lawrence Golan, a conductor who loves Peter and the Wolf but can no longer afford the fees the copyright holders charge for the sheet music. I listened to David Bowie’s narration of Peter and the Wolf (something that may have not even been created if Peter and the Wolf hadn’t been in the public domain at the time) about 100 times growing up, so the prospect of not being able to take my children to see a live performance of the piece is a real bummer.

The legal fight centers on the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreements Act, an international trade deal that gave a slew of foreign creative works new copyright protections in the United States. University of Pennsylvania film professor Peter Decherney took to the New York Times op-ed page this week to outline some of the works affected by the law:

Among the potentially millions of creations that lost their public-domain status were Sergei Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf,” Picasso’s “Guernica,” the British films of Alfred Hitchcock, Astrid Lindgren’s earliest Pippi Longstocking books, stories by H. G. Wells, the drawings of M. C. Escher, Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis,” Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” and Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will.”

Instead of being able to use and adapt these works at will, Americans now often have to pay high fees to the individuals and businesses that have claimed the long-public works (some by long-dead authors) as their own.

The Constitution allows Congress to establish copyrights for “limited terms” to “promote the progress of the useful arts.” But Golan and his supporters argue that once terms end—and if they’re set at zero, as they were for many foreign works before the law changed, they end immediately—Congress can’t just go back and retroactively assign copyrights to public works.

The plaintiffs also argue that the 1994 law presents a First Amendment problem. As Chief Justice John Roberts put it during the oral arguments, “One day I can perform Shostakovich; Congress does something, the next day I can’t. Doesn’t that present a serious First Amendment problem?” Don Verilli, the new solicitor general, longtime foe of copyright reformers, and a damn good lawyer (he’s been on the winning side of most of the most important copyright cases of the past decade or so), argued it didn’t—and in any case, Congress has done similar things in the past. (In 1897, for example, Congress created an exclusive right for the public performance of music, and made it applicable to previously existing copyrights. One day you could perform other people’s music in public without fear of retribution, and the next day you couldn’t.)

Verilli seemed to get the upper hand in the oral arguments, but the final outcome of the case is a mystery—even more so than usual with the Supreme Court. Only eight justices are hearing the case; Justice Elena Kagan recused herself since she was involved with the case as soliticitor general. Justice Clarence Thomas, as usual, didn’t say a word or give a clue about his position on the case. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg seemed like a sure vote for removing Peter and the Wolf from the public domain, and Justice Stephen Breyer seemed like a sure vote against it. But the Chief Justice only flirted with the First Amendment argument, and Justices Alito, Kennedy, and Sotomayor were hard to read. Whatever happens, the final decision is unlikely to split along traditional ideological lines. (In the case of a 4-4 tie, Golan would lose and the law would stand.)

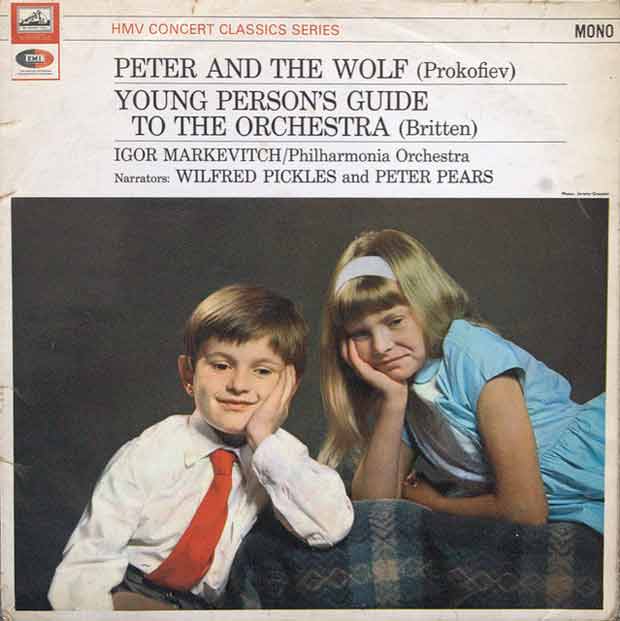

If you want more on this case, the Washington Post‘s Robert Barnes has a good roundup of the background, and you can many of the legal briefs on the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s web site. Bowie’s version of Peter and the Wolf is available on YouTube, but I can’t embed it. It won’t play unless you click through. Here’s a photo of a hilarious album cover for a (non-Bowie) version, though:

DaveBleasdale/Flickr

DaveBleasdale/Flickr