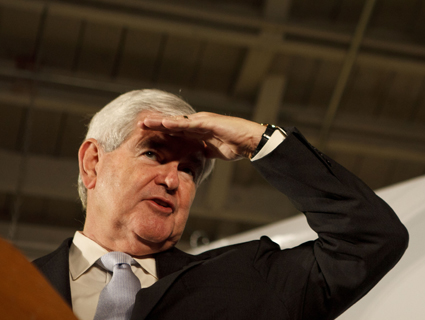

Hipster Newt Gingrich was into protesting banks before it was cool.Robin Nelson/ZumaPress

As a service to our readers, every day we are delivering a classic moment from the political life of Newt Gingrich—until he either clinches the nomination or bows out.

Newt Gingrich won the gratitude of the tech world—and smut-loving Americans everywhere—when he fought against an Internet censorship provision in the 1996 Communications Decency Act. But his career as a free speech activist actually began some 28 years earlier, when the former speaker launched a campus occupation in defense of the student newspaper’s right to publish nude photos.

Although he had refrained from partaking in the counter-culture movements of the time, young Gingrich, while a graduate student at Tulane, became a rabble-rousing activist when the school administration censored two sexually explicit photos from a student newspaper. (One image depicted a nude male art professor standing in front of a sculpture of two figures engaged in intercourse). Gingrich denounced the administration for unfairly censoring materials that had been produced by students and funded by student activity fees. To correct the injustice, he formed a new activist organization, Mobilization of Responsible Tulane Students, to force the powers that be to step back.

With MORTS, which included members of the more radical Students for a Democratic Society, Gingrich led a march of 700 students to the school president’s house—where, according to Tim Wise’s account, Tulane president Howard Longenecker was hanged in effigy. He followed it up by leading boycotts against a number of local businesses whose executives sat on the Tulane board of trustees, among them Merrill Lynch and another local bank. When he secured a meeting with Longenecker, Gingrich played hardball:

He threatened the university president with disrupting campus life for weeks if he did not relent. “It is now a question of power,” the brash young man told university president Herbert Longenecker, according to minutes of the meeting that NEWSWEEK discovered in Tulane archives. “We are down to a clash of wills.”

As Gingrich explained to the alumni magazine Tulanian in 1995, “Our argument was that it ought to have intellectual freedom because it was a student newspaper…I told [the school president] that we were paying for it and had a right not to be censored by the people who were not paying for it.” MORTS’ agenda extended beyond nude photography. As Steve Gillon reported in The Pact, Gingrich’s followers later occupied the student center, demanding that (among other things) the administration turn the school’s swimming pool into a public bath. Gingrich also pushed to give students a role in the hiring and firing (and promoting) of faculty and all major university decisions—an assault on the Ivory Tower that’s echoed in his more recent broadsides.

Despite his feverish protests, the nude photos were ultimately not published, and Gingrich’s taste for activism was short-lived. After leaving Tulane, his views on student activists have changed considerably. In a 1984 book, Window of Opportunity, he blamed the “social decay and disorder” of the 1970s and 1980s on the Free Speech Movement. By November, he’d descended into outright hippie punching. Asked about the Wall Street Occupiers at a forum in Des Moines, he had a simple message for th 99-Percenters: “get a job, right after you take a bath.”