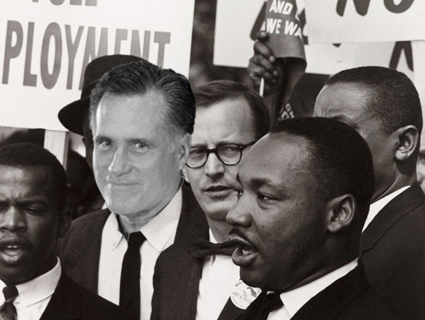

Mitt Romney says he watched his dad march with Martin Luther King Jr. He later clarified that he had done no such thing.Photo Illustration: Michele Eve Sandberg/ZumaPress; Courtesy National Archives

On Monday, the five remaining GOP presidential candidates will celebrate Martin Luther King Day by gathering in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina and debating Rick Santorum’s thoughts about Mitt Romney’s response to Newt Gingrich’s condemntation of Newt Gingrich’s super-PAC’s attack on Mitt Romney’s record at Bain Capital. Or something like that. The timing of the Fox News debate hasn’t been lost on folks like South Carolina Democratic Party Chair Dick Harpootlian, who suggested on Thursday it showed a lack of regard for the life of the Civil Rights icon.

The other, probably more plausible explanation is that, with the primary scheduled for Saturday, Monday was just an obvious date to hold the first of two debates. But it does raise the question—one that could come up in some iteration during the debate: How do the GOP candidates feel about Dr. King and his civil rights legacy? Here’s a quick guide:

Mitt Romney: It was at a Martin Luther King Day parade in Jacksonville, Florida in 2008 that Romney made the ill-considered decision to chant the lyrics to the Baha Men’s hit single, “Who Let the Dogs Out?” Except instead of posing it as a question, he seemed to supply the answer: “Who let the dogs out. Who. Who.”

His attempts to discuss King’s legacy have gone about as smoothly. In 2007, the former Massachusetts governor told an audience in College Station, Texas, “I saw my father march with Martin Luther King.” But as David Bernstein reported, that wasn’t quite right. There was no evidence of Romney’s father, George, marching with MLK at Grosse Pointe, Michigan, as the campaign had claimed; for one thing, MLK had never been to Grosse Pointe. The campaign later clarified that George Romney and MLK had marched together in a metaphorical sense—they were in different cities, and the marches took place on different days—and that Mitt (who was not present for either event) had seen his father march in a metaphorical sense as well. Romney’s justice advisory committee includes failed Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, who has written that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 established “a principle of unsurpassed ugliness.”

Ron Paul: The Texas congressman called King “one of my heroes,” but his record on the subject is a fair bit murkier. The Ron Paul Survival Report, published under his name at a significant profit, refers to MLK Day as “Hate Whitey Day,” and describes King himself as a “pro-communist philanderer” who “seduced underage girls and boys.” Although he has disavowed the contents of the newsletters, Paul did, as the newsletter proudly reported, vote against the bill establishing a holiday celebrating the civil rights icon—twice. Paul’s supporters contend that the candidate really did support the holiday and tout a 1979 floor vote to prove it, but as Ta-Nehisi Coates explains, the vote they point to as evidence was not a vote to create the holiday.

Paul is also opposed to one of King’s signature accomplishments: The Civil Rights Act of 1964. He cast a symbolic vote against the law in 2004, and told CNN’s Candy Crowley in January that, while he abhorred segregation, the landmark legislation “destroyed the principle of private property and private choices.” That’s the same argument made in the newsletters, where Paul (or his ghostwriter) explained that King “replaced the evil of forced segregation with the evil of forced integration.”

Newt Gingrich: Gingrich voted to make MLK Day a federal holiday in 1983 and broke into politics as a Nelson Rockefeller-style moderate, one who was conscious of Southern conservatives’ nasty record on civil rights and who seemed determined to move beyond it. He also voted for the 1984 Civil Rights Act extension, albeit somewhat grudgingly. In 2010, he warned that the Affordable Care Act was the most radical piece of legislation since the 1960s, and gloated that: “They will have destroyed their party much as Lyndon Johnson shattered the Democratic Party for 40 years” by signing the Civil Rights Act.

In May, Gingrich, who has lavished praise on King, proposed reinstating literacy tests for voters—an impediment to the democratic process that’s prohibited by the Voting Rights Act because it was specifically used to disenfranchise black voters. In January, he took heat for promising to go to the NAACP convention and speak truth to power on what he perceives to be the debilitating influence of social welfare programs like food stamps. Although for very different reasons, a long-standing beef with the NAACP is, at least, one thing that Gingrich and King had in common.

Rick Santorum: Santorum cites King as a model for how faith can inform policy debates. “Did Kennedy reject desegregation because black ministers like the Rev. Martin Luther King arguing from a Biblical premise advocated it? Thank goodness he didn’t,” he said in a 2010 address in Houston. He went on to quote extensively from King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” But for the former Pennsylvania senator, King’s defense of basic human rights went well beyond segregation; in an interview with CNS News last January, he used King’s defense of natural law to argue that we have an obligation to impose moral values on public policy issues like abortion. That line of argument led to this bomb, in reference to President Obama: “I find it almost remarkable for a black man to say ‘now we are going to decide who are people and who are not people.'”

Rick Perry: In August, Perry caused a minor outcry when he told reporters in Rock Hill, South Carolina that the fight against government regulation and taxation was the civil rights struggle of our time. In his book, Fed Up!, he seeks to preempt a “supernovel” gotcha question about his states-rights views by heaping praise on the Civil Rights Act of 1964: “The Civil Rights Act, which, among many things, prohibited private discrimination in so-called public accommodations, such as hotels and restaurants, was the glorious fulfillment of the principles of the Declaration of Independence and, ultimately, the intent behind passage of the Reconstruction Era amendments. I believe there was ample basis for the establishment of that law in that following the Civil War the people ratified three amendments, the purpose of which was to give the federal government the power to fight racial discrimination.” When he was still considered a viable candidate, the Washington Post reported that Perry’s family had for years rented a West Texas property known as “Niggerhead” Ranch.