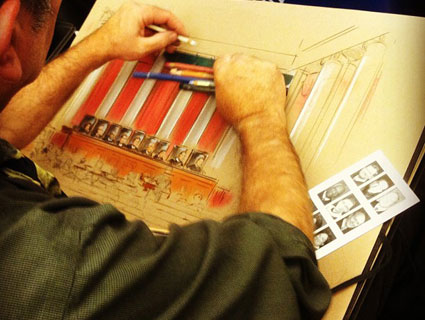

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/22417710@N00/359348158/">(a)artwork</a>/Flickr

Marla Tipping’s 14-year-old son, Cam, has to have his blood cleaned every two weeks. He has a rare condition that makes his body produce too much cholesterol.

Tipping says her family has had “to be absolutely vigilant in never having a lapse in coverage…because many carriers would never carry you with a preexisting condition again.”

That was the case before the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Now, children like Cam cannot be denied coverage because of a preexisting condition. (Similar protections for adults are set to start in 2014.) While Tipping says she and her husband still pay between $20-25,000 out of pocket every year for costs their insurance won’t cover, the ACA at least guarantees that they’ll be able to find some kind of policy for Cam, even if they are forced to leave their current plan.

Likewise, Stacie Ritter, a mother who participated in protests supporting the ACA’s passage, no longer has to worry if her twins, who have a rare form of leukemia, will be denied coverage if they have to change insurance providers.

“This law protects them from being discriminated against if my husband lost his job,” Ritter says. “Right now what’s protecting us is the fact that my girls can’t be discriminated against; we don’t have to fear that we don’t have access to insurance. That’s a really scary thought if the law is repealed.”

Most of the speculation over the fate of the Affordable Care Act has focused on the individual mandate and what the decision could mean for the 2012 presidential election. However, if the Supreme Court decides to throw out large parts of the law along with the mandate, Tipping’s family is one of millions that could lose the benefit of provisions that are already in place.

When it issues its decision, the Supreme Court has a handful of options: It could uphold the law, strike it down, or allow only certain portions to stay on the books.

“There are basically five ways this could come out. None except upholding the law are good,” says Donald Berwick, who until December 2011 served as administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, where he helped implement early provisions of the Affordable Care Act. “The implications of the law going away are dire for millions of Americans.” Given all the provisions already in place, any changes spurred by the court would also be an administrative nightmare. “It would be logistically very, very difficult,” Berwick adds.

The high profile parts of the bill, like the mandate, don’t kick in until 2014, but defenders of the law point to several parts that are already active that would be taken away if the Supreme Court struck the entire law down. Aside from banning discrimination against children on the basis of preexisting conditions, the National Center for Health Statistics estimates that about 2.5 million young Americans have benefited from being able to stay on their parents’ health insurance until age 26. Seniors no longer have to spend thousands of dollars out of pocket before qualifying for assistance paying for their prescription drugs—help that fills the so-called “doughnut hole.” The Affordable Care Act has also eliminated the cap on lifetime benefits, which means people with serious health problems won’t find themselves overwhelmed with health care costs because their insurance company no longer wants to help pay the bills.

Jeremy Aylward, who now works as an accountant for a hospital, was 12 years old when doctors discovered he had a congenital heart defect. At 22, he was booted off his father’s insurance.

Aylward says he was unable to find a workable insurance plan given his preexisting condition. “[I had] no affordable, realistic insurance coverage options,” Aylward remembers. Had the Affordable Care Act been in place, he would have been able to stay on his father’s plan, and wouldn’t have had to go without health insurance and pay out of pocket until a year later, when he found a job. Even then, his employer’s health insurance plan still kept him off for a year because of his preexisting condition and the fact that he had “allowed” his coverage to lapse.

It might seem extreme for the Supreme Court to throw out the entire law if they find only one part of it unconstitutional. But at least one of the justices has already explicitly endorsed the idea. During oral arguments over whether or not the mandate could be overturned separately from the rest of the bill, Justice Antonin Scalia said, “My approach would say if you take the heart out of the statute, the statute’s gone.” Opponents of the law are justifiably concerned about the infringement on individual freedom the mandate poses. But they neglect the very real restrictions on freedom that the law rectifies by ensuring and extending health care coverage.

The Affordable Care Act remains unpopular, despite the provisions already in place. Even some of those benefiting from the bill think it’s not an ideal piece of legislation. Ritter, who followed the oral arguments at the Supreme Court, simply wishes for a single-payer system.

“I don’t believe our health should be a product. I don’t believe we should be a commodity. I don’t think my life and well-being should be for sale,” Ritter says. “It’s big business playing with people’s lives. I can’t understand why [Obamacare opponents] are not angry about that.”