Private security firm Securitas touts the effectiveness of Segway guards in educational settings.Securitas

At a no-questions press conference in late December following the tragic shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, National Rifle Association executive vice president Wayne LaPierre announced a bold new multibillion-dollar proposal to end school shootings: Put an armed security guard or police officer in every school in the country. LaPierre commissioned a special task force to develop the plan, and deputized Asa Hutchinson, a former Republican congressman from Arkansas and director of the Drug Enforcement Agency under President George W. Bush, to head the effort.

But there’s something the LaPierre didn’t mention: Hutchinson sits on the board of directors of Pinkerton Government Services, a subsidiary of one of the nation’s largest private security contractors, Securitas. And if the NRA’s—and Hutchinson’s—proposals are enacted into law, Securitas, a firm Hutchinson once lobbied for in Washington, could stand to score big.

Hutchinson’s private security connections were first reported by Sally Jo Sorensen of the progressive blog Bluestem Prairie. As Sorensen noted, Securitas paid Hutchinson and the firm he worked for, Venable LLC, $200,000 for lobbying services in 2006. (Hutchinson also lobbied on behalf of Point Blank Body Armor in 2007 and 2008.)

Over the last three weeks, Hutchinson has made an evolving case for LaPierre’s agenda in a series of interviews and op-eds. After first suggesting that it might be possible to staff schools with armed volunteers, he offered a pricier proposal in an op-ed for the Arkansas Democrat–Gazette on Friday: “A part of this solution will be the increased presence of trained, armed and professional security officers in schools.”

Schools shouldn’t accept just anyone to keep watch, Hutchinson argued. “[N]ot every school can afford the costs, and not all armed officers are equally trained,” he explained. “That is why it is so critical to create an effective federal, state and local sharing of costs, and, most importantly, to assure a high standard of training and certification. The training of armed personnel to protect our children should not be less than those who are trained to protect our airlines or even the president.”

Hutchinson did not disclose his connections to the private security industry, but told Mother Jones his role with Pinkerton was in a regulatory advisory role. “I am not aware that PGS provides any school security services,” he said in an email. “I have no connection to Securitas as I am a proxy board member under Department of Defense guidelines to assure that there is no foreign influence or control over PGS. There are some very specific legislative and regulatory requirements in reference to my work as a proxy board member.”

Hutchinson is right about PGS. Bob Maydoney, a company spokesman, says the firm does not provide security for schools. Instead, Pinkerton Government Services specializes in security programs for government agencies and their contractors, offering, among other things, armed and unarmed security guards, EMTs, firefighters, and bicycle patrols.

But Pinkerton does have a Florida-based program, the Pinkerton Training School, developed “for the purpose of training security minded individuals and help them prepare to enter the field of professional security.” Chris Reed, a spokesman for the academy, said the program is a necessary step for armed guards of all stripes. “Before you get that license you have to take a 40-hour class,” he said. “We offer that class. And if we hear of any openings, we let them know.”

A more likely candidate for a school safety contract, though, is Pinkerton’s mother company, Securitas. According to Lynne Glovka, the firm provides security guards at “several hundred schools across the nation.” On its website, the company cites the need to prepare for “lockdown” situations.

“From weather emergencies and lockdown situations to bullying and violent assaults, educational institutions face a myriad of unique security threats,” the company explains in a brochure. “And as school officials across the country well know, high-profile incidents can happen anytime, anywhere.”

Glovka, who noted that armed security guards make up just a fraction of the firm’s 90,000 employees in the United States, could not definitively say whether Securitas would be able to fill the kinds of positions outlined by Hutchinson: “There are lots of hypotheticals involved—state licensing requirements, contractual issues, etc.”

Private security is a $66 billion industry in the United States. After LaPierre’s December address, The Atlantic‘s Matt O’Brien estimated that putting armed guards in the 76,000 public schools that currently lack them would cost about $4 billion. Hutchinson offered a lower figure, between $2-$3 billion. Either way, that’s a lot of cops—or a potential boon for private security providers and those who train them.

This isn’t Hutchinson’s only connection to a private security firm. His consulting firm, the Hutchinson Group, has also done work for Xe Services, the reincarnation of the infamous private security firm, Blackwater.

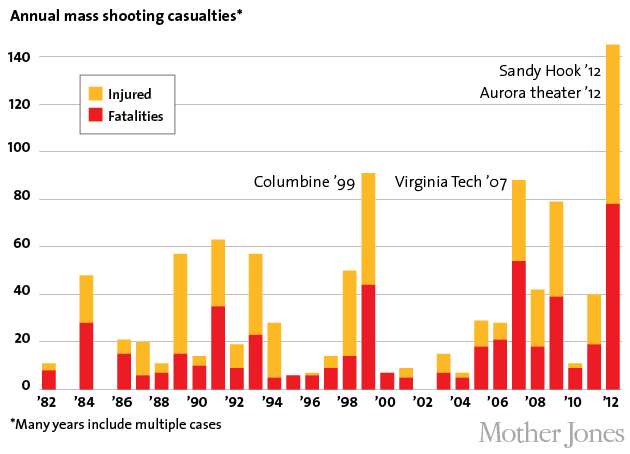

Potential conflict of interest aside, there’s also little evidence that armed guards are an effective deterrent to school shooters. Columbine High School had an armed guard in 1999 when two shooters murdered 12 students and a teacher. Virginia Tech had the equivalent to a SWAT team on campus in 2007, when a gunman killed 32 students and injured 17 others. The NRA has also run into opposition from unlikely allies like the American Federation of Teachers and NRA-endorsed Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.).