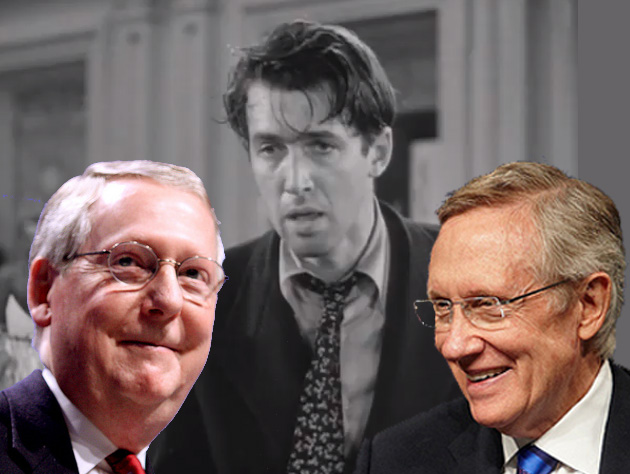

From left: Mitchell McConnell, Jimmy Stewart filibustering in "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," and Harry Reid. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/5437433261/sizes/z/in/photostream/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr, Columbia Pictures /<a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BL-Jg7CyqLQ">movieclips</a>/YouTube, <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/americanprogressaction/4972157648/sizes/z/in/photostream/">americanprogressaction</a>/Flickr

After more than a week of negotiations, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) cut a deal for the filibuster reform package that sailed through the Senate on Thursday. Unfortunately for fans of real filibuster reform, who expected Reid to win at least some GOP concessions—like a proposal by Sen. Al Franken’s (D-Minn.) that would force the minority party to muster at least 41 votes to continue a filibuster, rather than force the majority to find 60 to end it—the final package looked strangely like the minority-friendly one proposed last month by Sens. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Carl Levin (D-Mich.).

The first part of the Reid-McConnell deal, Senate Resolution 15, creates a temporary “standing order” that will expire with the end of the current Congress in 2015. The second part, Senate Resolution 16, is a permanant change. Here’s a breakdown on what it accomplishes—and doesn’t.

Motion to Proceed

The package offers the majority two ways to address a filibuster of the “motion to proceed,” which precedes the actual consideration of any given bill, as follows:

1) The standing order says that if the majority party guarantees the minority party two amendments, then the filibuster is dead. (However, “non-germane” amendments—amendments deemed not directly relevant to the bill—would require 60 votes to pass.)

2) With the new permanent rules, majority and minority leaders could simply agree to ditch an early filibuster and move on to the motion to proceed. The change will speed things up a bit in other ways, too: To end a filibuster, the majority must submit a “cloture” petition to limit debate. But the old rules don’t allow a vote on a cloture petition until after an entire business day has passed. Under the new rules, a petition signed by both leaders and seven members of each caucus can be voted on the day after it is submitted. As one of Reid’s aides admitted to me, this change is almost identical to what McCain and Levin proposed, only weaker: McCain-Levin would have required just five members from each caucus, plus the leaders, to green-light these super-petitions—and under their proposal a vote could occur after just two hours of debate.

Presidential Appointments

Each party has accused the other of holding up its nominees, and these changes are designed to keep the process moving along. The standing order limits debate following a cloture vote on Level I presidential appointments and judicial nominees to 8 hours (as opposed to the current 30), and 2 hours for district court appointments. This is stronger than the McCain-Levin package, which didn’t change post-cloture debate time on “Cabinet Officers, Cabinet-level Officers, or Article III judges.”

Number of Motions

The Reid-McConnell package changes, from three to one, the number of motions necessary for a bill to make it to conference committee, but it still allows a filibuster on that motion. It also allows a vote on a cloture petition two hours after it is filed. In these ways, it is identical to the McCain-Levin proposal.

Dial-in Filibusters

The leaders reached a sort-of “gentlemen’s agreement” that senators must make the effort to show up on the Senate floor if they want to filibuster. They won’t have to stand and talk, like some reformers wanted, but they would at least have check in personally at the start of the process.

While both Senate bills passed with strong bipartisan support (78-16 and 86-9), not everybody was pleased with the result. Sens. Mike Lee (R-Utah) and Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) each proposed amendments, but they were shot down.

In the end, the Senate is heading into another session relatively unchanged, with the minority as powerful as before, and McCain and Levin getting almost everything they wanted. While observers say that Reid could have easily gotten a better compromise package by pushing a bit harder on some elements, he didn’t. Now we’ll have to wait two more years, most likely, for this debate to resurface in the next Congress.