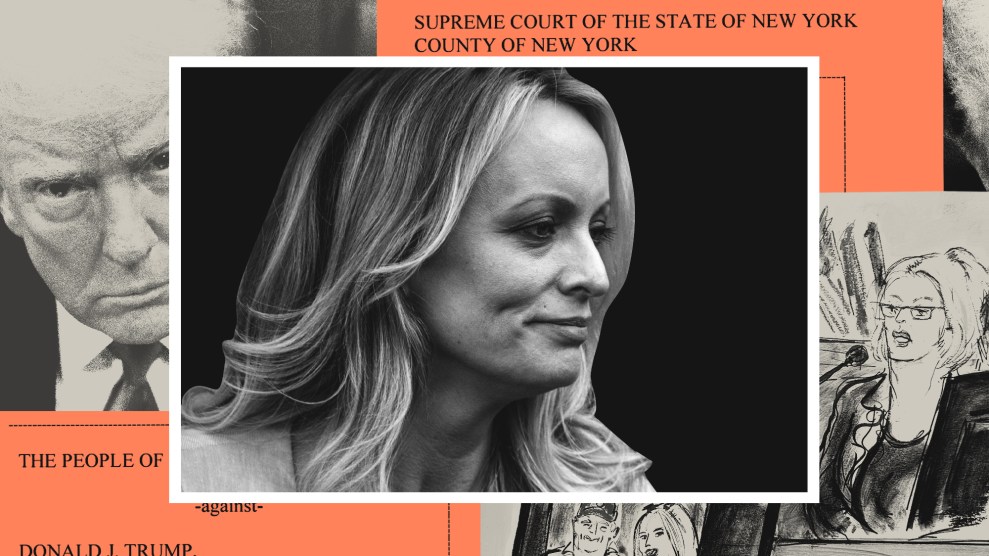

David Barron, ICCF founder<a href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LTan1EKVU2I">ICCFoundation</a>

Mother Jones insisted that before my investigation of congressional conservation junkets went to print, I try everything I could to get a response from the colorful figure who launched and then left the shadowy foundation at the center of the story. So, after spending over four months reporting on ethically questionable trips arranged by the International Conservation Caucus Foundation, I got a hold of a man with a deep Southern drawl and—if he was who I thought he was—first-hand knowledge of ICCF’s junkets.

“Is this David Barron?” I asked.

“This is,” he said.

After that came a long series understatements, the first of which was my own: “I’ve been trying to reach you in regards to your involvement with the International Conservation Caucus Foundation.”

My previous attempts to contact Barron had entailed, among other things, emailing several addresses I had for him and calling a series of listed and unlisted phone numbers associated with him using my Brooklyn cell phone number, blocked numbers, and my roommates’ phone at all hours of the day and night. He did not respond to any of the emails and did not answer any of the calls. He didn’t have a voicemail.

Then—calling on my girlfriend’s phone one January morning four days before the story was set to print—I got lucky.

“Do you have a moment to talk?” I asked him.

“Corbin, I’ve got a lotta of time. But I don’t want to participate in this interview,” Barron said. For some reason, though, he did anyway.

At multiple points in our polite but confrontational conversation, Barron said he’d had enough and would only sit down for a future interview if it was published in full. But Mother Jones enjoyed this one so much that it decided to honor his request.

The transcript of the 40-minute talk that follows opens with me trying to convince Barron to stay on the line or at least agree to schedule a meeting. It has been only lightly edited, with just our ums, ahs, ya knows, and unintelligible crosstalk removed and missing words added in brackets. I’ve also added occasional footnotes to explain why I asked what I did—and how Barron’s answers didn’t always tell the whole story.

Corbin Hiar: When would you be available to sit down then?

David Barron: Well, I come and go from Washington occasionally.1 I don’t think I’m going to be there any time soon.

CH: Well. that doesn’t really work for us because we’re going to be publishing this story—we’re finishing it up this week.

DB: Well Corbin, listen. I was very much part of getting the ICCF started, and it’s a wonderful organization, and they’re doing a great job with it. I’m delighted to offer a little advice and support occasionally. But I’m doing other things. It’s their story now, it’s not mine.

CH: And what are you doing now?2

DB: I’ve got a lot of other interests, including in conservation. I’m in business, and I’m still doing other conservation work. But I’m very happy to be living in South Carolina. You know, I’m spending time in Latin America and Africa—doing conservation work in other places. And I think [ICCF president] John Gantt and his crew are doing a great job with that organization. But I’m just not ICCF anymore. It’s a great organization—

CH: If that’s the case, then why do you still go on the trips with them?

DB: I very rarely—when our schedules overlap, it’s nice to be able to spend a little time with them. But I do very little of that. I have done very little of that for some time.3

CH: And when you go on those trips, who pays for your attendance?

DB: Corbin, ya don’t get it. We’re not gonna do this this way.

CH: I’m just, I’m working with a deadline—

DB: Corbin! Corbin, listen. Corbin, you’re a smart guy, okay? I come from a media family. I understand how it works. You know that you ask a question, you get a long answer, and then you take a piece of it and do whatever the hell you want with it to create whatever the hell your perception already was. I’m not going to play that game. I’m not a damn fool.

CH: Sir, I’m going to take what you say and compare it with the documents that I’ve assembled—

DB: Corbin, Corbin, listen. I don’t want to be rude to you, but we’re not going to do this. I’m happy to have a full, long discussion with you, at some point, under certain conditions, in writing. And that is: You ask questions, I answer questions, my entire [answers] are printed.

CH: We can possibly work that out, after the story runs. It’s going to run both printed and on the web—

DB: I’d be delighted to do that. But listen, it’s your story, and it’s their story—it’s not my story.

CH: Well you play a pretty significant role in it. And I’d like to get your take on it, to the extent that that’s possible.

DB: I hope you shoot straight. But I don’t even intend to read the article. I’m just not that interested, frankly.

CH: Do you want to comment on your previous work for General Sani Abacha?4

DB: [Silence.] Corbin, I never worked for General Sani Abacha. John asked me that question, I answered the question, he gave you the answer.5 I worked for Nigeria, as I did other governments, for several times. The presidency of Nigeria changed hands four times while I was working for other officials in Nigeria.6 I never met the man, I never talked to the man, I never liked the man. I was sorry as hell he took over when he took over. It was a power grab and throughout the entire process—before, during and after—I was supporting good, center-right democrats in the country, trying to do the right thing.

CH: Okay. I also—

DB: You asked the question—you actually told somebody on Capitol Hill, who reported it back, that I had worked for Charles Taylor, which is a damned lie. I not only never worked for him, I volunteered against the son of a bitch. Now you gonna call them back and tell them that was a damn lie?

CH: The folks who I’ve contacted on Capitol Hill have not responded to my inquiries.

DB: You told somebody on Capitol Hill I worked for Charles Taylor.

CH: And they proceeded to—

DB: Who told you that?

CH: That was a mistake on my part, sir.

DB: Who told you that?!

CH: That was a mistake.

DB: Well, whoever told you that’s a goddamn liar! It’s so absurd it shows that absolutely no damn work was done! There’s nobody that knows of my involvement in Liberia that doesn’t know that that’s a goddamn lie! It’s the complete opposite of the truth!7 Call President Amos Sawyer. He’s still available. I called President Sawyer, who I did work for—the wonderful democratic hero in Liberia, who hired me and for whom I worked. When he was gone, I volunteered for him and his followers for years to try to throw that son of a bitch Charles Taylor out. I’ve done far more pro bono work trying to help democrats in Africa than I have anything else. And Charles Taylor was a bloody monster.

CH: And that absolutely—

DB: I’m the one who released the story8 when he murdered Catholic nuns and left them in the damn swamp—

CH: That absolutely will not be in the story—

DB:—getting funding out of the Defense budget into the State budget to shore up our bloody embassy there. Listen…Corbin. I’m sure you’re a wonderful young guy. I hear you’re getting into the energy business. It’s wonderful. Energy management is one of the most important things we can be doing in this country. But my involvement in the ICCF was a passion of mine—to help get that organization going. And now my involvement is in other parts of the world doing other things. It’s not in Washington. I left Washington. I’m very happy to have left Washington over three years ago. I’m living back in the South where I belong. And there’s an extremely capable staff there doing wonderful work—not under the easiest circumstances. And a lot of it is because they’re being accused of things that they’re not doing. And I hope that you’re not—I hope that you’re doing something constructive and not destructive. Because it would be a bloody crime.

CH: I’m asking questions. And there’s a lot of things they haven’t been very forthcoming about. There’s—it specifically says on their taxes that audited financial statements are available. They’ve not been willing to turn those over. I’ve spoken with the former IRS director for tax-exempt organizations, and he’s raised some serious red flags about their taxes. They’ve proceeded to amend their taxes. I mean, this is not—I’m not creating something out of nothing here. So I’m just trying to ask the questions—

DB: Corbin, you’re trying to. You’re trying to—

CH: No, I’m absolutely not—

DB: They’ve never hidden a damn thing. They’ve never hidden a damn thing; they’ve never attempted any damn thing. They’ve got very good lawyers, they’ve very good accountants that do all of their legal and all of their accounting work for them.9 There are no lawyers and accountants on that staff. Everything they can to be as transparent as possible—they don’t print the names of their donors, because why the hell do that? So everybody else can beat their damn door down? I mean, it would be an absurdity. Nobody does that. It would be stupid to do that. They’ve gone to extreme lengths, not only to comply with the letter of the law, but to comply with the intent of the law in all of these things. Almost all of the conservation partners over the years—wonderful partners—would like the organization to have done more in the way of influencing policy. And the ICCF just says: “No, we don’t do that. You can do that. We don’t do that.” And the ICCF model is a wonderful model. It’s an educational foundation. It’s a great resource. It’s a collaboration of Audubon to Exxon.10 It’s organizations from all over the country, all over the world,11 and all over the political spectrum that provide awfully good information in various fora, in which policymakers can get better information to make better decisions. But they’re not knocking on doors asking for votes and things. They don’t need to! Other people do that. That’s not their model. They’re not doing that. And if you’ve got some damn smarmy former IRS guy who’s saying, ‘oh well these guys are a bunch of damn crooks, and this is what they’re really doing,’ he’s a damn liar! He doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about! I mean, he’s shooting from the hip. I mean, either you are taking more from what he’s saying or—I don’t know anything about the guy. I don’t trust anonymous anything.

CH: He’s not anonymous12 —

DB: You know, if they’re anonymous that they’re cowards. But what you suspect is that they’ve probably also got some bloody agenda of their own. You probably suspect that they’re really back-biting, sniveling…ex-something or other. I don’t know anything about this guy. And I suspect he doesn’t know much about the organization. My understanding—and all I know about this is a couple emails—is that you’ve sent questions, and they’ve sent answers. But what I hope is that when you connect your dots, you’re drawing accurate conclusions. That you haven’t started out to write a story, and that you then wanted to build a little flesh around it to look like it was actually objective. I don’t know what the hell you started with. I don’t know why you started on it. But there’s a whole lot of great work being done. And I hope whatever you do helps that success for the cause of conservation globally and isn’t some damn cute shot to do damage.

CH: Well some of the dots that I was connecting were the [Justice Department] reports that you filed as a part of Barron-Birrell. I’m wondering, in particular, why you filed about a decade’s worth of them on the same day right before the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act went into effect.

DB: I suspect that that’s not correct, but I don’t have any idea what you’re talking about.13

CH: Okay. I’m also wondering —there was a $400,000 a year contract that you had with [former Gabonese President] Omar Bongo. By my calculations that means that from the 2004—2002 date?—sorry, I don’t have it in front of me—that it opened until it was closed in 2007, Barron-Birrell collected $1.4 million dollars off of that contact. Is that accurate?14

DB: I never had any involvement in Barron-Birrell after 2005—and I don’t remember whether it was early or late 2005. So I have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about now. Barron-Birrell didn’t exist after 2005.

CH: The final disclosure form was filed and, I believe, signed by you in 2007.

DB: Well it wasn’t for work done after 2005.

CH: On the form, you claimed that it closed in the end of 2006.15 [Pause] I’d be happy to send you—

DB: Listen, I don’t have that in front of me. I don’t know. The reality is that there are books that closed after a certain date because of whatever. But I never saw Omar Bongo again after early 2005. I ceased to do business with Jeff Birrell because we—he was off in another direction, and I wasn’t going in that direction. I ceased to do business with Jeff Birrell in 2005. I haven’t been in Gabon since—I don’t even remember, but I think early 2005. I had a great relationship with President Bongo from 1998 until about 2004. And I went on to do other things.

CH: Well I stopped by Jeff’s office, which is in the same place where you previously had Barron-Birrell, and the receptionist seemed to know who you were, and said that you had been by in the last year or so. So, was that not a work visit? Or…?

DB: [That] doesn’t have anything to do with Jeff Birrell. I know other people in that space too. I haven’t even had a meeting or phone call with Jeff Birrell since 2005.

CH: Okay.

DB: Nor an email.

CH: What ended up happening to him after the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations report came out? I contacted him, and he—

DB: I have absolutely no idea. I have absolutely no idea. And I’m not even particularly curious.16

CH: Okay.

DB: I’ve been sent articles by people who thought I would be, and I erased them. I didn’t want to read them. I wasn’t interested.

CH: And so, in terms of your current work right now, are you working for any African governments right now?

DB: Corbin. [Pause.] You do your work well. You make sure you can back up everything, and try to put things in perspective.

CH: We’re doing the best we can, sir.

DB: If you’re not lying about some things, that’s fine. I hope you’re not lying about them as an honest journalist. But put things in perspective.

CH: I’m trying.

DB: If good work’s begin done, recognize it. I don’t know what your intent is when you started this thing. Was this article your idea or somebody else’s idea?

CH: It was mine.17

DB: Have you been involved in conservation before?

CH: I actually, once upon a time, was an intern for the Nature Conservancy.

DB: It’s a great organization—

CH: I had a very good time.

DB: You ever spent some time in the field?

CH: I did, I was an invasive species intern in Maine.

DB: In the US. Have you ever been to Africa, Latin America, and gotten out into the wild places?

CH: I have not.

DB: Well you should sometime. It could change your life. It’s like getting religion. Especially when you visit one of these wild places—that are full of wild animals and surrounded by wonderful people with a great culture of living with those animals—that’s under terrible threat. You realize that it’s not just their livelihood—their safety—that’s at risk.You realize that it’s their very culture, it’s the history of their peoples that’s at risk in the modern era where there are not a lot of solutions, and where a lot of organizations think the answer is to remove the people. Where the answer really is to include the people. Where the answer is to release the marketplace. Where, if these people rather than competing with these animals can live complimentarily—and I mean to benefit from them. That the value of these natural resources can be unleashed so that it benefits them. And in a sustainable manner. And sustainability means that it will benefit their future generations, too. But if you can unleash the value of those natural resources for the benefit of those people—feed their children, build their economies, to create stability in their region—then you’ve created a market paradigm that will implicitly protect those animals and that habitat—at least in some manageable, viable, sizable manner. Yes the world and those on tours and that sort of thing can participate in and enjoy, but that the local people can benefit from directly, and see the value of, and appreciate a model that will allow them to extract enough enough from it—if you will, like income from an annuity—so that they benefit from it. But if they protect the—

CH: One follow up question for you on that concept: Isn’t that threatened by—

DB: I wish you’d gotten out some to see some of this—

CH: I certainly hope to. Isn’t that—

DB: I appreciate bright young kids that know everything from books. But it’s a very different world to actually get into these societies and economies and to see the challenges—the very, very complicated challenges—and yet the very important needs.

CH: Now, aren’t those societies threatened by climate change?

DB: Listen. I mean, everybody knows the climate’s changing. And there are a lot of things that cause that. And I’m sure some of it’s man-made. But you’ve got to put things in proportion. And yet, what you don’t do is you don’t shut their economies down in the meantime while you’re actually trying to approach solutions to the longer-term problems. Listen, we hear more about climate change when we visit leaders in the developing world than we do in our own country.18 They’re very well aware of these issues and most of these wonderful NGOs that are working in these communities —we don’t do conservation on the ground, but what we try to work on is the utilization of resources and the way that can provide value to the local people. And in exchange for that, to solidify their commitment to parks and protected areas and long-term planning and that sort of thing.

CH: But is part of the reason—

DB: We’re not part of the climate debate, for or against it.19 Any more than we’re debating gravity or inertia. It’s just, it’s just…natural resource management, good natural resource management, has been what that organization has worked on for a long time in Washington, and which I continue to work on in other parts of the world.

CH: And does that include, and I’ll ask you this again, working for other African governments now?20

DB: I haven’t worked for—i.e., being compensated for—any government in quite some time. I may again some day. I just happen to be very busy doing other things right now.

CH: And what does that entail? I know you’re on the board of a few conservation organizations. But beyond that, what sort of businesses are you working in, if you don’t mind me asking?

DB: I still do some work in Africa and other places, but not for governments. I’m involved in agriculture and tourism and other things.

CH: Okay.

DB: Corbin, I’m sorry we can’t meet.

CH: You know, I’d be happy to to meet with you at a later point. But I’m just trying to ask the questions that—

DB: Well, you’re gone now.

CH: Sorry?

DB: You’ve left the magazine, I’m told.21

CH: Ah, I’m a freelancer.

DB: Ah, okay. Well, I thought you’d gone to work for an energy company.

CH: That’s my day job, yes. But also in journalism.22 Yeah so, I’m just trying to make sure that I’m giving you an opportunity to respond to all the questions that we’ve raised here.

DB: Corbin, I saw messages that you were offered that opportunity. I really haven’t wanted to participate in this article. I’m former ICCF. And I applaud the organization, and I am delighted to support when I get a call from any of them, to give advice or direction or that sort of thing. I’m delighted to help. But they’ve got a great team. And they are in Washington and focused on the people who are in Washington. I stay out of Washington as much as I can. I spent thirty years in Washington, doing what I could. But I’m back where I belong, and I love being here. I love being in the low country, where I take walks in the afternoons and see alligators and great blue herons and egrets and osprey and white tail on my evening walk before the sun goes down most days. I’m glad I’m out of the jungle [laughs]. I’m glad I’m back in the marshes.

CH: All right.

DB: Listen Corbin, let me go. I’ve got things to do, and I’ve got folks waiting for me. But I wish you the best. I feel better about your tone having heard your voice.

CH: It’s good to talk to you too.

DB: I hope you get a little bit of this passion in your soul. And I hope you stay involved in the conservation world. The first thing, as they tell doctors, is don’t do any damage. I suspect your article is written, as I suspect basically your conclusion was written before your started the article. But—

CH: I’m just asking questions, Mr. Barron.

DB: The ICCF has shifted the paradigm in Washington by bringing a far wider audience into the debate, into the discussion, into the information circles to make better informed decisions. And it’s a great thing for conservation. There are a lot more policymakers and opinion leaders interested in viable solutions for good natural resource management than there were before this collaboration of a lot of good NGOs and companies and that little shop on a pretty modest budget23 does a very good job of collecting, synthesizing, and emanating good information so that audience can make better informed decisions. In the words of Bill Archer, the former chairman of the Ways and Means Committee that was the first former chairman of the ICCF, a long time ago, when the discussion was held about lobbying or not lobbying, Archer said “adequate education obviates lobbying.” And that became the mantra of that organization. It was a deliberate decision made: Don’t do it! The rules say you can do so much of it. You can count it, and you can add it, and you can track it and the rules say you do so much of it, and there was a lot of pressure from partners to do some of it, because there was very good access. The decision was made: Don’t do it—

CH: One of the pieces the questions the piece asks, though, is—

DB: It’s been continued as the mantra: Adequate education obviates lobbying. Write those words down—

CH: I wrote them down already—

DB: Adequate education obviates lobbying!

CH: But if the education doesn’t include climate change—which is, according to most government bodies and scientists—the biggest threat to conservation, is that education adequate?

DB: It’s not, it wasn’t, I guess it still isn’t, I don’t know—it could be more on the agenda now than it was. But when I left there, now more than three years ago, climate change was not an issue —more because it was polarizing than anything else —but was not an issue that ICCF dealt with, primarily. But every time ICCF invited people to participate in a conference or a briefing or a program or whatever, from whatever the spectrum was —NGO and corporate —who had this concern, tended to speak to it—even though at that time, it wasn’t our focus.24 More because there were other issues that were easier to develop a consensus on faster to get something done. The point wasn’t to avoid the debate of anything that was of concern, it was to pick some issues in which a consensus could be developed on to get something done, sooner than later—not to pass a litmus test. Have we made a statement on everything? Do we have an opinion on everything? I don’t know whether that’s true now or not. You’d have to ask [former Congressman and current ICCF Chairman] John Tanner or John Gantt or somebody else.

CH: Yeah, they’ve continued to avoid discussing climate change. The conservationists outside of the organisation that I’ve been speaking with see that as a pretty significant oversight in terms of the direction of the group.

DB: Well it become extremely polarizing—even among the NGOs. And frankly, most of the corporations that we’ve dealt with were more—at least in the early days, in the now, lord time flies, but several years ago—it was high on their priority list. This is why so many of those corporations have gone our of their way to develop their LEEDs programs, to lessen their footprint. Almost every major corporation developed some lessening of a foot print company policy. Some of course became extraordinary. I mean, Walmart was a game-changer. Walmart’s upstream-downstream impact was so dramatically shifted that they at first weren’t sure that it wouldn’t be enormously costly to the company but they said they had to do it anyhow because it was the right thing to do. Well you know what? Rob Walton’s dying brother said—literally had this as his last request—the CEO Lee Scott at the time was extremely committed to it, and what happened was, of course, they created efficiencies.25 They started making money. They realized we can do the right thing, and make it pay for itself. But now you’ve got companies like Unilever that—it’s been some time since I’ve been in one of their briefings. But go into their—research them.26 The commitments they’ve made in lessening their impact in, by 2015 in this area, and 2020 in other areas is unbelievable. You’ve gotta ask why. It’s a lot of things. Most of it comes down to what we used to call pollution. But it’s all environmental impact. And it includes all of the above. And yet, they—it also involves—it’s health and water. And it’s forest, and it’s air, and it’s all of those things. When I was involved in ICCF, the decision was made to focus on the nexus where something could be done, and that nexus was chosen as forest. Deforestation contributes more carbon emissions than the global transportation industry does. So if you’re a conservation organization, why not focus on forest? So if you’re an international conservation organization, why not focus on forest?! Where you can do something about it?27 Instead of venting your spleen and being politically correct and howling at the moon like everybody else and waiting for the government’s hind tit to fund whatever you’re going to do?

CH: Some of the organizations I’ve spoke with have said that, by assenting to avoiding the issue, conservation groups like those involved with ICCF are making it more difficult to actually pass any comprehensive climate change legislation.

DB: Well, listen. You’re getting into a whole other issue here. And that is one that you and I ought to have at a table when you’ve got a tape recorder and you promise to write everything. I’ll give you the hottest bloody damn story you ever wrote on conservation if you want to do that sometime. But it’s gonna be under my rules. And that is, that my answers are gonna be answers in total. But I’m not in that game right now. We’ll do that some time down the road. I’ll tell you when I’d like to do that. I’d like to do that sometime after you’ve visited the bush and seen the difficulty of actually applying some of these theories on the ground. I’m not involved in the ICCF. ICCF doesn’t have a media shop, but I’d be delighted to do it some time. Hell, I’ll take you on safari, and I’ll let you visit some of the communities. I’m serious! I’m serious as hell.

CH: Well, I’ll be touch after this comes out. There will probably be some follow up—

DB: In your new job, when Mother Jones is behind you, and you’re still interested in conservation—and I’m glad to hear that you did that internship at TNC, because something deep down inside must have been itching. Let me tell you something. If you could go to central Africa and spent a little bit time with [ICCF advisor] Mike Fay, the visionary, the pied piper that walked through central Africa, 2,000 miles over 15 months with not one a team of pygmies—he wore one out, and he had to pick up a second team of pygmies—and where he did a Lewis and Clark-type expedition. He collected vast data. It took seven people a year and a half to catalogue all of it at the National Geographic. And they said it would be—I can’t remember whether he said if it was 50 years or 200 years—it was gonna be decades actually digesting the data. They effectively just dumped in places where it was retrievable. I won’t go into more detail. You can read about it in National Geographic [magazine]. But Mike has a tremendous vision of not just Central Africa. Mike has a global vision. But Mike had dedicated much of his life to central Africa. And he has a vision of how the power of the marketplace can be released. You’ve never met a more dedicated conservationist in your life. But he’s got his head screwed on right. I mean Mike understands market forces. He’s an idealist. But he’s also practical. You know, Mike is one of these folks that, for instance, doesn’t hunt, hasn’t hunted, doesn’t want to hunt, not real happy about it—but he understands that hunting is an important part of the design for releasing market value in some places. And so he’s not anti-hunting.28 Listen, you’d love Mike Fay. He’s a brilliant, brilliant guy. Master’s in botany, PhD in primatology, and one of the toughest guys in the world. He has literally lived in one pair of Patagonia shorts and no top, worn out two pair of Tevas, and full of worms, and full of—I mean, more worms than you can imagine—in his nails, in his blood, in his intestines. Mike has lived under the most difficult circumstances in the world and he just thrives in it. And yet he’s so damn passionate. And he’s so extremely well educated. And even out in the middle of nowhere—thanks to satellite or whatever—he stays very well informed of what the hell’s going on in the world. If you could spend a few days—Nick Nichols, the photographer at National Geographic, and David Grummand? David? David…oh hell, I can’t remember his name. Dave spent time with Mike. Have you looked at Geographic, by the way? At some of the stories on the Congo basin and Mike? They’ve done about a dozen stories on him over the years.

CH: Yeah. Mother Jones also wrote about it a bit too.29

DB: Quammen! David Quammen. Q-U-A-M-M-E-N. Princeton grad. Brilliant guy. Brilliant writer. He’s got some books out. Quammen, doing the story and Nichols—Nick Nichols they call him, but Michael Nichols is his byline. But Geographic has done a lot of stories on Mike. You should go spend some time with Mike. Right on the front lines, where the elephants are being slaughtered, and where the oil companies are operating and where the pygmies are still hunting like their ancestors. And yet the modern world is on their doorstep—not excluding, by the way, Islamic extremists, and caravans supported by neighboring countries, invading the—taking everything from gold to ivory—be pretty damned exciting story for you.

CH: Absolutely. Well, Mr. Barron, I would like to sincerely thank you for taking a moment to talk with me here. And I am interested in sitting down with you at a future date if we can work that out—

DB: Corbin, I promise that I’ll do it. And I’m sincere about taking you into the bush. But if you misquote me or quote me out of context, don’t call me again, okay? Because I won’t trust you.

CH: I’ll tell you what I am going to do. The story is mostly written at this point because I’ve been trying to reach you through ICCF and trying to email you and call you and stuff. So at this point I can add in your perspective, which I think will make this story much more balanced and fair. But the way I’ve connected dots may not be the way that you feel about the organization. So I think the two of us—

DB: Well, you’re welcome to your opinion.

CH: Yeah, I think—

DB: And I’m not saying your opinion has to be the same as mine. But not misrepresenting the facts in order to draw a reading public to one conclusion when you know that it may not be the correct conclusion is dishonest.

CH: All I’m doing is asking questions here. And you’ve answered a lot for me, and I do really appreciate it.

DB: Thanks, Corbin.

CH: Yup. Have a good day, Mr. Barron.

DB: Take care. Bye.

CH: Bye.

1. A former GOP staffer who’s attended some of the ICCF’s DC luncheons and dinners suggested that Barron visited more often than he let on. “He is the face of the ICCF and also puts a lot of work into it,” the ex-aide told me. Jump back

2. Since 2008, Barron has listed his occupation on federal campaign contributions disclosure forms as everything from “executive” and “consultant” to, more confusingly, “farmer” and “MIII.” But who—if anyone is paying for him to interact with lawmakers is more interesting to me than what he calls himself. Jump back

3. Despite stepping down as president in 2009 and no longer receiving a salary from the organization, Barron has gone on four of five trips the ICCF has put on since then. And the one he missed only included mid-level staffers. Jump back

4. This brutal Nigerian dictator ordered the internationally condemned execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other nonviolent environmentalists activists who had opposed oil drilling in the Niger delta. Jump back

5. ICCF President John Gantt did not respond to my request for an interview with his predecessor. But he did email me detailed, second-hand responses to some of the questions that I said I needed to directly address to Barron. Jump back

6. This is surprising because Barron’s firm only registered two Nigerian contracts with the US Department of Justice during that period. The first was signed in 1992 by an official in General Ibrahim Babangida’s government and the second by an Abacha regime adviser in 1995. Jump back

7. Barron was both onto something here and justifiably upset. I had seen that his former firm filed reports for work with the Liberian government around the time Taylor’s reign began, jumped to an incorrect conclusion, and asked the offices of the three lawmakers who had travelled to Kenya with Barron to comment on it. As I later learned when I found the initial Liberian contract, Barron’s company was representing the embattled government of national unity, not Taylor’s regime. Jump back

8. Here is the one of the news reports Barron was referring to. Jump back

9. The foundation’s accountants, Berlin Ramos & Co., claim they “misinterpreted the instructions” when they filled out “incorrect” returns on behalf of the ICCF. Jump back

10. Although both organizations were members when Barron was leading the ICCF, the National Audubon Society has not been a member since 2007, according to the foundation’s annual Partners in Conservation publication. ExxonMobil is still a dues-paying member of ICCF. Jump back

11. One of these international members is the Malaysian Palm Oil Board. The industry it represents is blamed for the country’s rapid deforestation rate, which was three times faster than all of Asia combined, according to a 2011 study. Jump back

12. As the story mentions—and I tried to here—the name of the former IRS official is Marcus Owens. On the record, he alleged that “ICCF is lying to somebody.” Jump back

13. Barron was not correct. Here are the 15 biennial reports, covering a period from mid-1998 through the end of 2006, that he filed with the Justice Department on Sept. 10, 2007. The Honest Leadership Act, which barred registered foreign agents like Barron from leading congressional groups like the ICCF, was then enacted by President George W. Bush on September 14. Ben Freedman, an investigator at the Project on Government Oversight, a Washington watchdog group, told me that “filing all those supplementals late is technically illegal.” Luckily for Barron, the Bush administration didn’t audit a single foreign agent’s filings from fiscal year 2004 through FY2007. Jump back

14. According to the Justice Department filings, I was about $100,000 off. In September 2002, Barron’s firm signed a $100,000-per-quarter contract with the Gabonese government. It terminated that contract, and the firm, at the end of 2006. So Barron’s company was contractually entitled to at least $1.3 million. Jump back

15. I was correct, and it appears that Barron was not. He signed the aforementioned contract termination in May 2007, and it was received by the Justice Department that September. It claimed that his firm Barron-Birrell Inc., “was officially terminated as a corporation on 12/31/06.” Jump back

16. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations accused Barron’s former business partner, Jeffrey Birrell, of setting up shell companies to help Bongo to “purchase six US-built armored vehicles and obtain US Government permission to buy six US-built C-130 military cargo aircraft from Saudi Arabia to support his regime.” None of the people I contacted for the story said they knew what happened to Birrell after those allegations were made. But I reached him by phone, so I’m certain he wasn’t in jail as of early January: “I don’t have any comment, but thanks for calling,” he said before hanging up on me. Jump back

17. I read this story, and it got me thinking. Jump back

18. A major reason for this is because ICCF-member ExxonMobil and other polluting corporations have so lavishly supported efforts to undermine the American public’s faith in the reality of climate change and government’s ability to do anything about it. Jump back

19. Barron told the trade publication Greenwire in 2007 that he was “more scared of the globalwarming debate” than of global warming itself. Jump back

20. I kept asking about the money because I knew Barron had met with lawmakers on the Hill and hadn’t filed any foreign agent disclosures with the Justice Department since 2007, when he declared his lobbying firm was no more. If he’d acknowledged being paid by foreign governments, that could have been a violation of the Foreign Agent Registration Act. Jump back

21. I interned in the DC bureau of Mother Jones until February 2010. Jump back

22. I now report for SNL Energy, a publisher of trade newsletters. Jump back

23. The ICCF’s budget has grown from a little over $1 million in 2007 to nearly $5.5 million in 2011, according to its most recent annual tax filing. However, since the foundation is currently amending its 2011 return, these numbers may not be correct. Jump back

24. Climate change still isn’t a focus for the organization: “We’ve always been agnostic about” climate change, ICCF communications director Adam Brooks told me. “It’s just not something we do because of the sensitivity of our audience.” Jump back

25. The foundation honored Walmart Chairman Rob Walton in 2011 with its “‘Good Steward’ Award for his lifetime of personal commitment to conservation.” The retailing giant, which had supported the ICCF since 2007, is no longer listed as a member on the foundation’s website and has had its dedication to sustainability questioned in a 2012 Mother Jones investigation. Jump back

26. Here’s the “sustainability strategy” of ICCF-member Unilever. Jump back

27. The ICCF has long talked about the importance of conserving forests. But it remained silent in 2011 when nearly 20 affiliated lawmakers supported efforts to roll back the Lacey Act— a highly effective law that punishes companies caught importing illegally harvested fish, animals, or plants—after Gibson Guitar Corp. was caught violating it. Jump back

28. Barron has sat on the board of the African Safari Club of Washington, according to his ICCF bio page. Jump back

29. Barron is named as one of Fay’s “powerful fixers” in a 2009 MoJo story about how Gabon’s new national parks threatened the indigenous people living in them. Here is National Geographic‘s take on the parks. Jump back