John Dean, a principal in the Watergate scandal, in 1975Ken Stewart/ZUMA Press

This is interesting. John Dean, Richard Nixon’s White House counsel and a star Watergate witness, has weighed in on the McConnell tape controversy. His take: This ain’t Watergate, and the making of the tape probably wasn’t illegal.

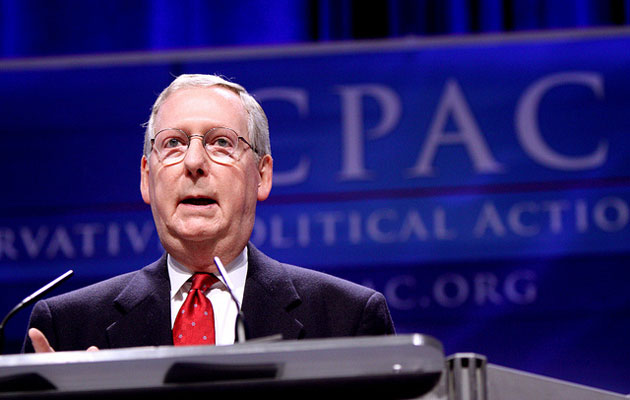

After Mother Jones and I disclosed a secretly recorded tape capturing Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and campaign aides discussing using actor/activist Ashley Judd’s past struggles with depression and her religious views as political ammo (should she challenge McConnell), McConnell and aides claimed the minority leader was the victim of a Watergate-style operation and called on the FBI to investigate. McConnell’s campaign manager, Jesse Benton, also played the Hitler card and compared the taping to “Gestapo” tactics. At the end of last week, local Kentucky media reported that two local Democratic operatives linked to a super-PAC called Progress Kentucky, Curtis Morrison and Shawn Reilly, were involved in the taping, having recorded a conversation they heard in a hallway after an open house at McConnell’s campaign headquarters in Louisville. Subsequent reports fingered Morrison more than Reilly. And Morrison has set up a legal defense fund without publicly acknowledging any role in the taping. (I did not comment on the media reports naming Morrison and Reilly because I had promised my source confidentiality.)

Dean, working off the media reports, begs to differ with McConnell’s historical analysis. He writes:

McConnell and his staff’s claim that this activity was a Watergate-like event is long on hyperbole, and short on historical accuracy. The only thing that appears comparable to Watergate in this situation is that operatives of the Progress Kentucky organization, which has been described as a “gang that can’t shoot straight,” were foolish and a bit bungling. Otherwise, it is not even close.

Watergate, as all but the youngest readers will know, was the 1972 surreptitious entry and effort to bug and wiretap the Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters on two occasions. On May 28, 1972, Gordon Liddy and his army of burglars and buggers successfully wired the DNC, but they failed to bug the office that they had targeted, namely, that of DNC Chairman Larry O’Brien (they never found his office). The wiretap they mistakenly placed on another phone picked up nothing but secretaries talking to their boyfriends; and the third bug they placed did not work at all. They returned on June 17, 1972 to fix the problems—and after that, they planned to move on to bug President Nixon’s opponent Senator George McGovern on Capitol Hill. But that never happened, because they were arrested at the Watergate after conspicuously leaving electrical tape on the door locks to keep them open, which the night watchman noticed, and which prompted him to call the police…

The Watergate break-in and bugging was illegal from start to finish…To call the activities at McConnell’s campaign Nixonian, or Hitler-like behavior, is so far over the top as to make the Senator and his aides appear stupid. Unlike in Watergate, there was no reported breaking and entering by Reilly and Morrison. And based on the available information, they did not go beyond the hallway, which was accessible to anyone in the building. If it was while in the hallway that they overheard and recorded the conversation that would hardly be a violation of federal law. Nor has there been any effort, so far, to cover up what Reilly and Morrison did.

Not a violation of law? Dean explains:

The applicable federal law appears to be Title III of the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), which prohibits wiretapping and electronic surveillance of many wire, oral, or electronic communications. Clearly, Morrison recorded an oral communication. Under the law, “oral communications,” by definition, include only face-to-face conversations taking place in a constitutionally protected area, and that type or area is defined as a space where the speakers have a justifiable expectation of privacy…

The key question is whether McConnell and his staff had a reasonable expectation of privacy. Merely the fact that they were behind closed and locks doors will not be determinative.

Dean writes that a quick review of case law he conducted “indicates that a conversation that could be heard in a public hallway would not be a protected oral communication under Title III of the ECPA.” He notes that the “expectation of privacy” standard was defined by the Supreme Court ruling in Katz v. US. In that case, a suspect was recorded in a telephone booth by the FBI and the court ruled, “What a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of [Fourth] Amendment protection.” Lower federal courts, Dean says, have found no privacy expectation in a lobby or in common areas of an apartment building. But here’s perhaps the most relevant citations:

Regarding overheard conversations in U.S. v. Llanes (1968), a federal court found no reasonable expectation of privacy for a conversation conducted within a home that was audible in a hallway. More strikingly, in a Pennsylvania case, Commonwealth v. Loude…the court found no justifiable expectation of privacy even within a home where the conversation was audible through the walls. (I noticed, when checking for additional facts, that George Washington Law Professor Orin Kerr has blogged on this subject, and he located federal cases with even closer factual situations, see, e.g., United States v. Carroll (1971), where a conversation was overheard and recorded through a hotel-suite door and the recording was found not to violate the federal statute.)

Dean sums it up this way: “It appears that a conversation that was overheard and recorded in a public hallway of the building where McConnell has his reelection headquarters is not covered by the federal statute.”

But what about state law? Dean points to a posting by Kerr at the Volokh Blog. Kerr notes that the Kentucky Crime Commission states that “[a] conversation which is loud enough to be heard through the wall or through the heating system without the use of any device is not protected by KRS 526.020. A person who desires privacy of communication has the responsibility to take the steps necessary to insure that his conversation cannot be overheard by the ordinary ear.” Dean observes: “Kerr suspects, as do I, that this state law is not any more restrictive than the federal law on this subject. (Kerr also found federal cases with even closer factual situations than the ones I have cited above.)”

Are Dean and Kerr correct? No doubt, other lawyers will see it differently. But their analyses at least suggest that this case (if the media reports accurately describe the taping) could fall into a gray area open to interpretation. Dean contends that the FBI is now involved because McConnell “wants the FBI there investigating to scare the hell out of those involved and local FBI Agents like to help out members of the US Senate.” He recalls that Nixon “would use any and all efforts and tactics to attack his enemies by any and all means that he could employ. Unfortunately, I suspect that is the same strategy that we will see from McConnell—and that, in the end will be the true Nixonian connection to this case.”