Tim McDonnell

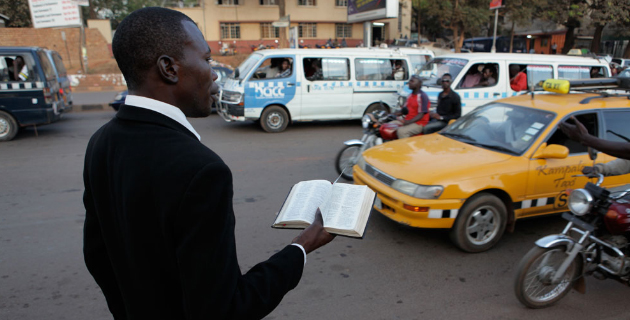

Central-West Côte d’Ivoire is a lush agricultural landscape, stuffed with rich banana, rice, and cocoa fields. The region is this West African nation’s equivalent of the corn belt of Iowa and Illinois. A long drive down stretches of road left pockmarked by the ongoing rainy season yields endless repetitions of the same scene: Tiny villages—each home to only a few dozen farmers living in thatched-roof huts—quietly tending to crops and livestock. Things are even more peaceful than usual now, as the Muslims that make up this area’s dominant religious affiliation celebrate Ramadan.

But as you arrive in Yamoussoukro, the nation’s capital, a strange monument can be seen towering over the horizon: An enormous gilded cross that adorns the top of what is, by many accounts, the world’s largest church.

Topping St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome by more than 80 feet, Basilica Our Lady of Peace in Yamoussoukro, sometimes called the “basilica in the bush,” is a jaw-dropping and bizarre monument to the end of a period only a few decades ago when Côte d’Ivoire was competing against other newly-independent African nations to become the cultural and economic powerhouse of the continent.

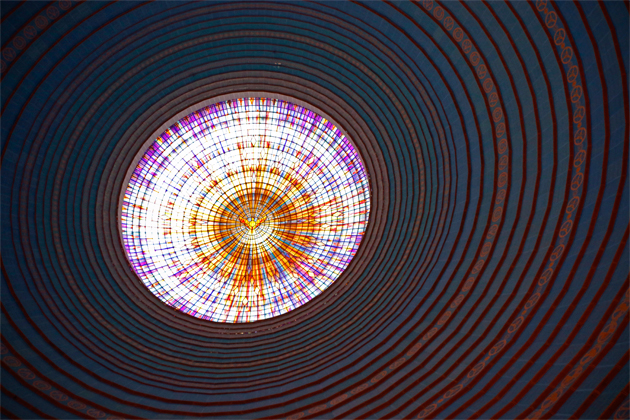

The raw numbers are stunning: Between July 1986 and September 1989, 1,100 workers cleared 178 acres of coconut grove, coated the space with 13 football fields-worth of European marble, and erected a 520-foot-tall structure, supported by 128 towering Doric columns, that can accommodate 200,000 worshippers. Inside are 24 stained-glass windows. The organ can reach volumes that lead to permanent hearing loss. The building is estimated to weigh 98,000 metric tons.

But probably the most interesting figure—how much it all cost—is shrouded in mystery: Although independent estimates pegged the price tag at about $300 million, then-President Félix Houphouët-Boigny was notoriously tight-lipped, preferring to refer to the construction as a gift from God (with help from his massive personal cocoa fortune).

“Most people think it also mostly came out of the treasury,” says Tom Bassett, a geographer and Côte d’Ivoire? historian at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne. For that reason, Bassett says, it got a second nickname: “Our Lady of the Treasury.”

The wealthy heir to one of the country’s largest cocoa operations, Houphouët-Boigny didn’t exactly choose the most opportune moment to publicly drain his nation’s cash reserves on what quickly came to be seen as less a glorification of God and more a vanity project straight from the “dictator handbook,” as the Daily Beast recently put it.

Houphouët-Boigny became Côte d’Ivoire?’s first president after the country gained independence from France in 1960 and ruled as a more or less benevolent dictator until his death 1993, overseeing what became known as a “miracle” period of economic prosperity in the 1960s and 70s. In 1983, he named his home village Yamoussoukro the new administrative capital and shortly thereafter set about planning the city’s crown jewel, the basilica. In keeping with a request from Pope John Paul II, who said he wouldn’t consecrate the building otherwise, the dome was made slightly shorter than St. Peter’s. But the addition of a towering cross atop the dome pushed the church above its counterpart in Rome.

But meanwhile, by the late 80s the country had fallen to economic ruin, hit simultaneously by a nosedive in cocoa and coffee prices, climbing oil prices, and disastrous mismanagement of state-owned businesses. Midway through the basilica’s construction, Côte d’Ivoire declared itself insolvent. At the same time, budget-resuscitation measures mandated by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank slashed basic services and key agricultural subsidies, drastically lowering the standard of living for most Ivorians—including those living on farms in the shadow of the basilica.

All this left Houphouët-Boigny wide open to scathing criticism for the unseemly contrast between the church’s opulence and the decay of the surrounding countryside; his public image wasn’t helped by a large stained-glass window just inside the dome that depicts him kneeling before Jesus on his entrance to Jerusalem. An unnamed Vatican official told Time that “the size and expense of the building in such a poor country make it a delicate matter.” Still, the Pope consecrated the basilica in September 1990, the only time the thousands of seats here have been full (and the only time a grandiose papal residence on the grounds has been occupied).

Since then, the basilica has been little more than a tourist destination; services are held weekly but are sparsely attended. In late 2002, while then-President Laurent Gbagbo was out of the country, disgruntled military leaders staged a coup that threw the nation into a bloody, two-year civil war. The basilica briefly came back into the limelight during this period, as Yamoussoukro became the heart of a UN-enforced buffer zone between rebel forces in the north and Gbagbo supporters in the south, where the country’s largest city, Abidjan, lies. Political leaders on both sides, aided by the national media, portrayed the conflict in part as one between a Christian south and Muslim north, with the basilica in the middle.

But in reality, Bassett says, demographic data never supported the existence of such a division—there are likely to be just as many Muslims in the south as in the north. And in any case, he says, “I don’t think the basilica really fits into that narrative.” So sorry, there are no heart-wrenching, The Sound of Music-esque scenes of embattled families taking refuge inside from machine-gun toting soldiers. It’s a ghost town, a highly-visible tombstone for a Côte d’Ivoire that died before it could be born.