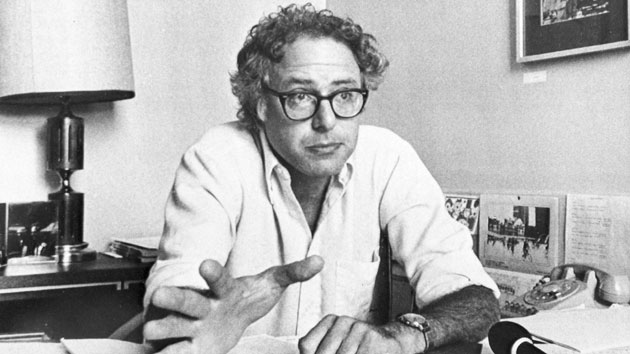

Bernie Sanders in 1981, a few months after being sworn in as mayor of Burlington, VermontDonna Light/AP

Editor’s note: Sen. Bernie Sanders jumped into the crowded 2020 race. This story was published during his first presidential bid. Click here for more Sanders stories from Mother Jones’ archives.

Sometime in the late 1970s, after he’d had a kid, divorced his college sweetheart, lost four elections for statewide offices, and been evicted from his home on Maple Street in Burlington, Vermont, Bernie Sanders moved in with a friend named Richard Sugarman. Sanders, a restless political activist and armchair psychologist with a penchant for arguing his theories late into the night, found a sounding board in the young scholar, who taught philosophy at the nearby University of Vermont. At the time, Sanders was struggling to square his revolutionary zeal with his overwhelming rejection at the polls—and this was reflected in a regular ritual. Many mornings, Sanders would greet his roommate with a simple statement: “We’re not crazy.”

“I’d say, ‘Bernard, maybe the first thing you should say is “Good morning” or something,'” Sugarman recalls. “But he’d say, ‘We’re. Not. Crazy.'”

Sanders eventually got a place of his own, found his way, and in 1981 was elected mayor of Burlington, Vermont’s largest city—the start of an improbable political career that led him to Congress, and soon, he hopes, the White House. On Tuesday, after more than three decades as a self-described independent socialist, the septuagenarian senator launched his campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in the Vermont city where this long, strange trip began. But it was during Sanders’ first turbulent decade in Vermont that he discovered it wasn’t enough to hold lofty ideas and wait for the world to fall in line; in the Green Mountains, he learned how to be a politician.

Not long after graduating from the University of Chicago, and fresh from a stint on an Israeli kibbutz, Sanders arrived in Vermont in the late 1960s on the crest of a wave. The state’s population jumped 31 percent in the 1960s and ’70s, due largely to an infusion of over 30,000 hippies who had come to the state seeking peace, freedom, and cheap land. Sanders and his then-wife bought 85 acres in rural Vermont for $2,500. The only building on the property was an old maple-sugar house without electricity or running water, which Sanders converted into a cabin.

Free-range hair and sandals notwithstanding, Sanders never quite fit the mold of the back-to-the-landers he joined. “I don’t think Bernie was particularly into growing vegetables,” one friend put it. Nor was he much into smoking them. “He described himself once in my hearing as ‘the only person who did not get high in the ’60s,'” recalls Greg Guma, a writer and activist who traveled in the same circles as Sanders in Burlington. “He didn’t even like rock music—he likes country music.” (Sanders did say in a 1972 interview that he had tried marijuana.) “He’s not a hippie, never was a hippie,” Sugarman says. “But he was always a little bit on the suburbs of society.”

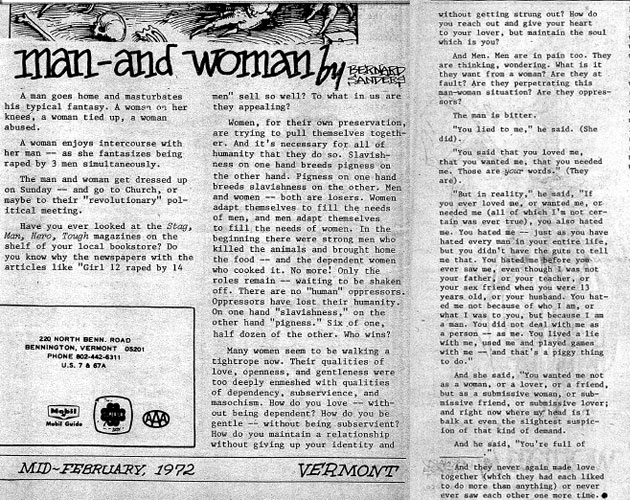

What Sanders did share with the young radicals and hippies flocking to Vermont was a smoldering idealism forged during his college years as a civil rights activist—he coordinated a sit-in against segregated housing and attended the 1963 March on Washington—but only a fuzzy sense of how to act on it. Sanders bounced back and forth between Vermont and New York City, where he worked at a psychiatric hospital. After his marriage broke up in the late 1960s, he moved to an A-frame farmhouse outside the Vermont town of Stannard, a tiny hamlet with no paved roads in the buckle of the commune belt. He dabbled in carpentry and tried to get by as a freelance journalist for alternative newspapers and regional publications, contributing interviews, political screeds, and, one time, a stream-of-consciousness essay on the nature of male-female sexual dynamics:

Sanders was aimless. Then he discovered Liberty Union.

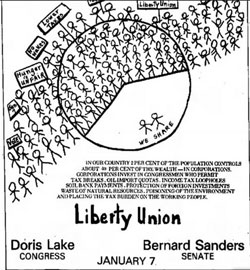

The Liberty Union Party was conceived in 1970 as part of an informal network of leftist state parties that would uproot the two-party system and help end the Vietnam War. In Vermont, the party’s leaders hoped to find a receptive audience amid the hippie emigrants. Its cofounder, a gruff, bushy-bearded man named Peter Diamondstone, had predated Sanders at the University of Chicago by a few years; Diamondstone likes to joke that they “knew all the same Communists” on the South Side.

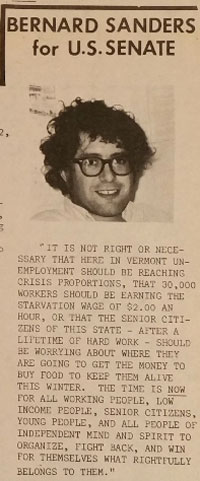

By the fall of 1971, Liberty Union was floundering. “We were lost as a political party,” Diamondstone says. That October, Sanders showed up with a friend at the Goddard College library, for a Liberty Union meeting. (The school was a favorite lefty gathering spot, and its alumni include Mumia Abu-Jamal and the members of the band Phish.) It was a large crowd by the group’s standards—maybe 30 people. The party was struggling to field a candidate for the upcoming Senate special election. Sanders, with dark hair, thick black glasses, and his two-year-old son in his arms, stood up impulsively in a room full of strangers. “He said, ‘I’ll do it—what do I have to do?'” Diamondstone recalls.

Sanders lost that race, the first of four losing campaigns over the next five years (twice for Senate, twice for governor). In addition to opposing the war, the party pushed for things including a guaranteed minimum wage, tougher corporate regulations, and an end to compulsory education. (Vermont’s schools “crush the spirits of our children” Sanders once remarked). Sanders floated hippie-friendly proposals, such as legalizing all drugs and widening the entrance ramps of interstate highways to allow cars to more easily pull over to pick up hitchhikers.

But through these campaigns, Sanders emerged as one of the leading voices within the organization and as its spokesman to the rest of the state. Within a few years, he was named Liberty Union’s chairman. “He was a mouthpiece, he was an orator—we called him ‘Silvertongue,'” Diamondstone says. During his 1972 campaign for governor, Sanders crisscrossed the state with the party’s choice for president—the child-rearing guru Dr. Benjamin Spock.

In those early years, Sanders, a member of the Young People’s Socialist League at the University of Chicago, was a true believer in what might be called small-s socialism, and had little patience for lukewarm allies. He believed in the need for a united front of anti-capitalist activists marching in step against the corrupt establishment. Guma recalled meeting Sanders for the first time at a campaign information session and asking why the candidate for Senate should get his vote. Sanders, in effect, told Guma that if he even needed to ask, Liberty Union wasn’t for him. “Do you know what the movement is? Have you read the books?” he recalled Sanders responding. “If you didn’t come to work for the movement, you came for the wrong reasons—I don’t care who you are, I don’t need you.” In interviews at the time, Sanders suggested that dwelling on local issues was perhaps counterproductive, because it distracted activists from the real root of the problem—Washington. Sanders started a small monthly zine to promote the Liberty Union’s agenda. It was called Movement.

“I once asked him what he meant by calling himself a ‘socialist,’ and he referred to an article that was already a touchstone of mine, which was Albert Einstein’s ‘Why Socialism?‘” says Sanders’ friend Jim Rader. “I think that Bernie’s basic idea of socialism was just about as simple as Einstein’s formulation.” (In short, according to the physicist, capitalism is a soul-sucking construct that corrodes society.)

Sanders built his campaigns against a theme that would sound familiar to his supporters today—American society had been pushed to the brink of collapse by plutocrats and imperialists and radical change was needed to pull it back. “I have the very frightened feeling that if fundamental and radical change does not come about in the very near future that our nation, and, in fact, our entire civilization could soon be entering an economic dark age,” he said in announcing his 1974 bid for Senate. Later that year, he sent an open letter to President Gerald Ford, warning of a “virtual Rockefeller family dictatorship over the nation” if Nelson Rockefeller was named vice president. He also called for the CIA to be disbanded immediately, in the wake of eye-popping revelations about the agency’s misdeeds.

But Sanders was beginning to question whether Liberty Union had a future. He drew just six percent of the vote when he ran for governor in 1976 (the three other campaigns didn’t fare any better), and he was drifting away from the global ambitions of Diamondstone, who was now advocating “a worldwide socialist revolution.” After the last American troops left Saigon in 1975, the anti-war party was faced with an existential crisis. And Sanders faced one of his own. Liberty Union could claim a few victories—it helped to defeat a telephone rate increase and secured more funding for state child dental programs. But he believed that absent a serious change, the party would never be anything more than symbolic.

“That’s what distinguished [Sanders] from leftists who were more invested in the symbolism than in the outcome,” Sugarman says. “He read Marx, he understood Marx’s critique of capitalism—but he also understood Marx doesn’t give you too many prescriptions of how society should go forward.”

Sanders had reason for introspection. He was struggling financially—a newspaper article during his 1974 race noted that he was running for office while on unemployment. His income came from sporadic carpentry and freelance articles, which made paying bills on time a constant struggle. Sanders, now single, was helping to raise a young son, and living in a city in which the working poor lacked access to daycare. Increasingly, Sanders’ political gaze was focusing on his own backyard.

Meanwhile, Sanders and Diamondstone clashed about the direction of Liberty Union—and pretty much everything else. “When I was on the road, I would stop at his house and I’d sleep downstairs, and we’d yell at each other all night long, and sometime around 3 o’clock in the morning, we’d say, ‘We gotta stop this,’ so we could get some sleep,” Diamondstone recalls. “Five minutes later we’d be yelling at each other again.”

Sanders quit the party in 1977, and dismissed Liberty Union’s future on his way out the door. “It certainly has not gone as far as I wanted it to go,” he told the Associated Press, “and in that sense it’s a failure.” (The relationship between Sanders and Diamondstone continued to deteriorate; when Sanders campaigned for Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale in 1984, Diamondstone followed him to every campaign stop, handing out leaflets calling the then-mayor a “quisling.”)

Sanders emerged from his experience with the Liberty Union as confident as ever of the need for radical change in the nation’s power structure, but less sure how to get there.

First, he had to get his life in order. “He was living in the back of an old brick building, and when he couldn’t pay the [electric bill], he would take extension cords and run down to the basement and plug them into the landlord’s outlet,” says Nancy Barnett, an artist who lived next door to Sanders in Burlington. The fridge was often empty, but the apartment was littered with yellow legal pads filled with Sanders’ writings. When he was eventually evicted, Sanders moved in with his friend Sugarman.

“The fact that neither of us could afford to live in the city where we worked was a source of great consternation to us and I think the beginning of a [mayoral] platform, honestly,” Sugarman says of their roommate days.

Sanders kept busy building a company he had started with Barnett called the American People’s Historical Society, which produced filmstrips for elementary school classrooms on topics including women in American history and New England heroes. It was a DIY operation—Sanders did all the male voices; Barnett did all the female ones. They used Sanders’ son’s walkie-talkies to create a beeping noise that would signal when to move to the next slide. The work took them up and down New England’s back roads, as they sold copies of the slides to school administrators. “His cars were always breaking down,” Barnett says. “He was extremely frugal. It was never important to him.” When it snowed, Sanders (or whoever was in the car with him) would have to reach into the glove compartment to pull out a spare wiper blade and clear the windshield manually.

Sanders had little interest in making a profit from his educational film enterprise. Instead, after his falling-out with Liberty Union, he poured his share of the profits into his pièce de résistance—a documentary on the life of union leader Eugene Debs, who won nearly a million votes running for president from prison on the Socialist ticket in 1920.

“We had gone to New York and lined up Howard Da Silva, who was a big Broadway booming voice actor, to play Eugene Debs’ voice,” Barnett explains. “But that didn’t quite work out, so Bernie ended up doing the narration of Debs’ voice.” Bernie Sanders is from Brooklyn; Debs was not. The movie also suffered from the filmmaker’s reverence for his subject. Sanders, one reviewer opined, seemed “determined to administer Debs to the viewer as if it were an unpleasant, but necessary, medicine.”

When Sanders tried to get the documentary aired on public television in 1978, he was rebuffed, either because of the political agenda, or because the documentary just wasn’t very good. Sanders, fearful perhaps that even humble Vermont Public Broadcasting had fallen under the dominion of corporate media, cried censorship and fought back. Eventually, the Debs documentary was aired. “That was a breakthrough of sorts,” Sugarman says. “That was actually our first successful fight.”

The incident only hardened Sanders’ skepticism of corporate power. Television, Sanders wrote in 1979, was a particularly pernicious evil, rooted in “the well-tested Hitlerian principle that people should be treated as morons and bombarded over and over again with the same simple phrases and ideas.” Television stations were “attempting to brainwash people into submission and helplessness.”

Not long after making the Debs documentary, Sanders got back in the political game. He ran for mayor of Burlington in 1981 as an independent, and he crafted a hyperlocal platform that cut across party lines—he opposed a waterfront condominium project, supported preserving a local hill for sledding, pushed to rein in utility companies, and urged bringing a minor league baseball team to town. His kitchen-table focus was underscored by his most popular campaign swag—free paper grocery bags with his name on them. Sanders was still, at heart, the neurotic socialist who picked fights with Diamondstone over Sigmund Freud’s controversial protégé Wilhelm Reich, but he recognized that voters in Burlington wanted to hear what he thought about Burlington.

He won by 10 votes out of 8,650 cast, knocking off the longtime Democratic incumbent Gordon Paquette. After a decade on the outside, Bernie Sanders finally had a foot in the door—and a steady job. “It’s so strange, just having money,” he told the Associated Press at the time.

In the mayor’s office, and later in the halls of Congress as a representative and then a senator, Sanders has followed a similar course to the one that got him to Washington. He’s unafraid to raise hell about the corporate forces he fears are driving America into the ground—replace “Rockefeller” with “Koch” and his Liberty Union speeches don’t sound dated—but always careful to keep Vermont in his sights. At times, Sanders has even showed a willingness to compromise that’s disappointed longtime ideological allies. He has supported the F-35, Lockheed Martin’s problem-plagued fighter jet that has led to hundreds of billions of dollars in cost overruns; Burlington’s international airport was chosen as one of the homes for the planes. “He became what we call up here a ‘Vermont Exceptionalist,'” Guma says, of the candidate’s pragmatic streak.

Sanders has made some cosmetic adjustments too. “He’s much more conscious of his appearance than he was,” Sugarman says. “When he was first elected mayor we had to go out and buy him a couple of ties—he didn’t own any.”

The earliest polls of the presidential race give former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton a commanding lead over Sanders, former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, former Sen. Jim Webb, former Rhode Island Gov. Lincoln Chafee, and whoever else is considering jumping into the field. But if Sanders defies the mighty odds to win the presidency, he and Sugarman may be reunited in Washington. Sanders has promised his old friend, who still teaches at the University of Vermont, the same position he held during the mayoral years in Burlington—an unpaid posting called “Secretary of Reality.”

Additional reporting by Levi Lee.

This article has been revised.