Yosemite was one of four national parks to regularly have unhealthy air pollution levels.Gary Tognoni/iStock

It’s late summer, and Americans are flocking to the country’s national parks for some recreation and fresh air.

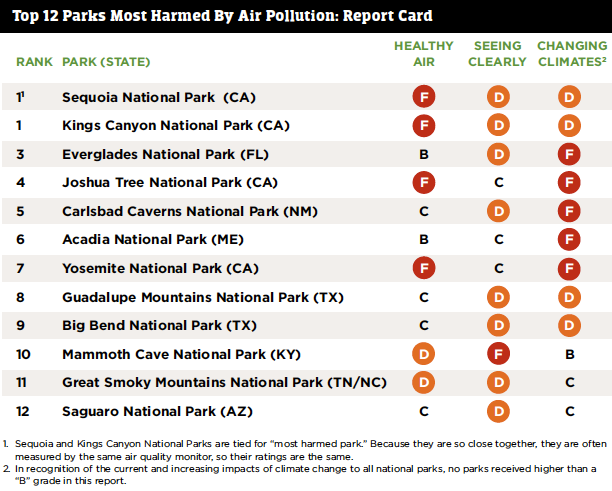

But a study released this week by the National Parks Conservation Association found that air in some of the country’s most popular parks is not so fresh—and it’s potentially hazardous. The report rated the country’s 48 parks in three categories: levels of ozone (a pollutant that can irritate or damage lungs), haziness, and the impacts of climate change on the park. Here are the 12 worst contenders (full list available here):

Ozone is a pollutant common in smog, and it’s particularly prevalent on hot summer days. Seventy-five percent of the parks had ozone levels between 2008 and 2012 that were “moderate” or worse, according to the federal government’s Air Quality Index. Four national parks—Sequoia, Kings Canyon, Joshua Tree, and Yosemite—regularly have “unhealthy” ozone levels, meaning that the average hiker should reduce strenuous activity and those with asthma should avoid it altogether. (You can see the air quality in your area here.)

Jobs at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, including those indoors, come with pollution warnings saying that at times the air quality “may pose human health problems due to air pollution,” according to the report.

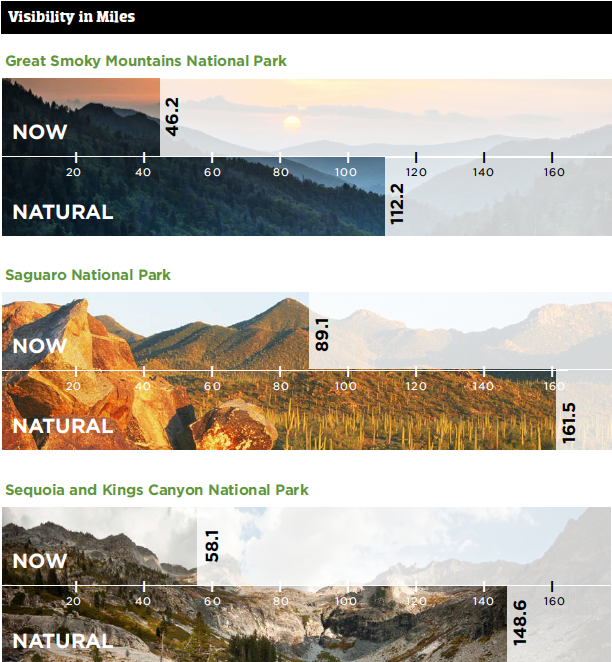

Pollution doesn’t just make visitors and employees sick; it also ruins one of the parks’ main attractions: the views. Smog affects vistas in all of the parks; on average, air pollution obstructs fifty miles from view. Here are some examples of how far visitors can see in miles today compared to “natural” levels, when air isn’t affected by human activity.

The NPCA didn’t look into specific causes of air pollution in each location, but generally, the the report attributes it to the the usual suspects: coal-fired power plants, cars, and industrial and agricultural emissions. Under the Regional Haze Program, developed by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1999, states are required to implement air quality protection plans that reduce human-caused pollution in national parks, the NPCA contends that loopholes prevent power plants and other big polluters from being affected by the rules.

Ulla Reeves, the manager of the NPCA’s clean air campaign, maintains that if enforcement for the Regional Haze Program isn’t improved, only 10 percent of the national parks will have clean air in 50 years. “It’s surprising and disappointing that parks don’t have the clean air that we assume them to have and that they must have under the law.”