Samuel D. Keenan/Planet Pix via ZUMA Wire

Reported suicides in Puerto Rico jumped more than 50 percent in the months after Hurricane Maria ripped through the island, according to a recent report from the local government’s department of heath.

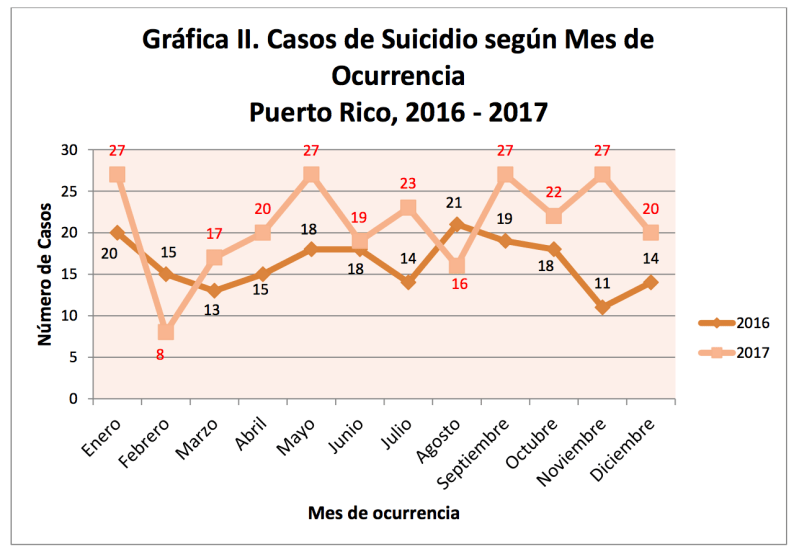

The report counted 27 suicides in September 2017 compared to 19 in September 2016. It also counted 22 in October 2017 (up from 18 the year before), 27 in November (up from 11), and 20 in December (up from 14).

The report, issued by the health department’s suicide prevention office, does not attribute the additional suicides to Hurricane Maria, which killed dozens and caused $95 billion in damage, according to the island’s government. While the official death count from the storm remains at 64, reporting by the Puerto Rico Center for Investigative Reporting (CPI), the New York Times, and others suggest the true figure could be more than 1,000. The Puerto Rican government has stopped issuing monthly updates to the death count, but has promised that a working group will issue conclusive data by April. CPI recently filed a lawsuit demanding data the island’s government has already collected, including death certificate information, and burial and cremation requests.

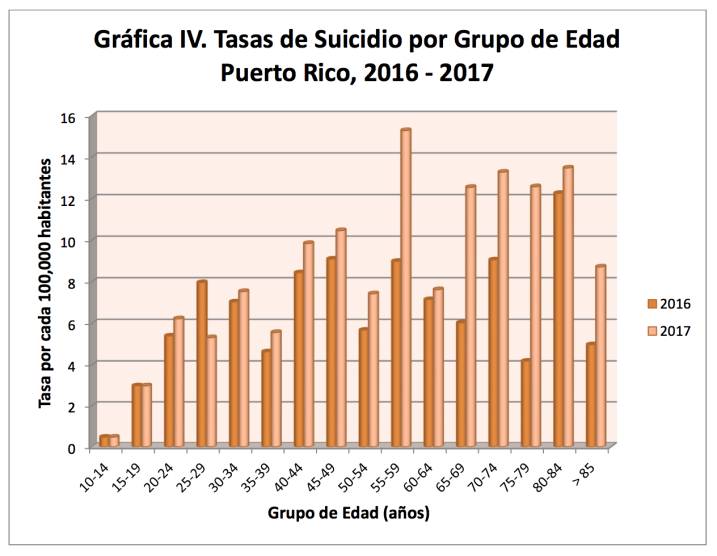

The report not only lays out the numbers of suicides, but breaks them down by age group, gender, and region. Among the various age groups, those older than 55 appear to have the biggest increase in numbers.

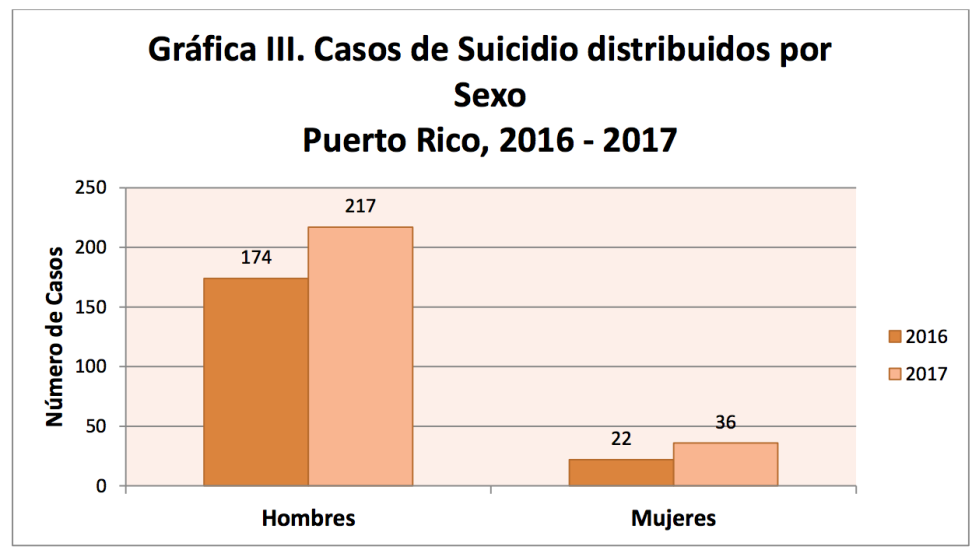

The total number of men who took their own lives in Puerto Rico saw a jump from 2016 to 2017 (174 to 271), and the number of women did as well (22 to 36):

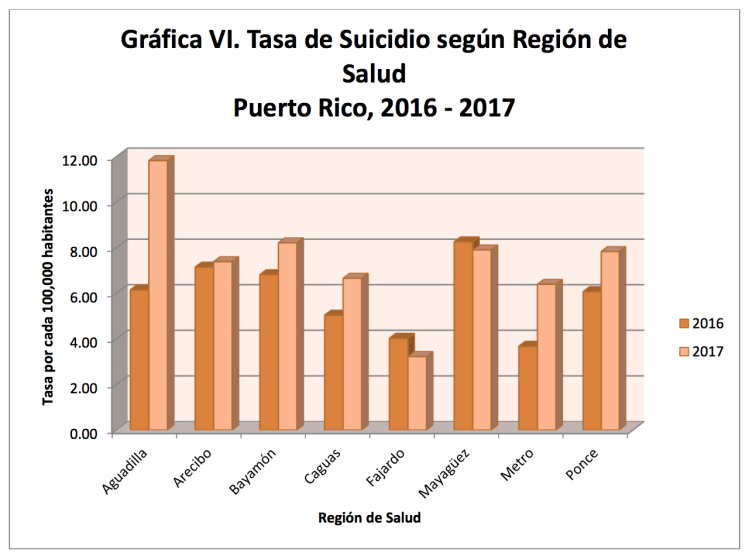

When broken out by region, the biggest jump was in Aguadilla, an area on the island’s northwest corner, which saw its total nearly double from 2016 to 2017:

The storm’s effect on mental health was the subject of a poignant New York Times mini documentary released late last year, which itself followed a separate Times piece examining the mental health crisis predicted after the hurricane. The damage caused by the storm—which included destroying much of the island’s electrical grid, wiping out communications infrastructure, and knocking out water supplies for months (in some places it’s still out)—effected an island already dealing with a decade-long economic crisis and high unemployment, the Times noted.

“And this is all happening at once,” Dr. Domingo Marqués, the director of clinical psychology at Albizu University, a prominent graduate school of psychology, told the Times’ Caitlin Dickerson. “What we have lost is the foundation that holds a society together.”