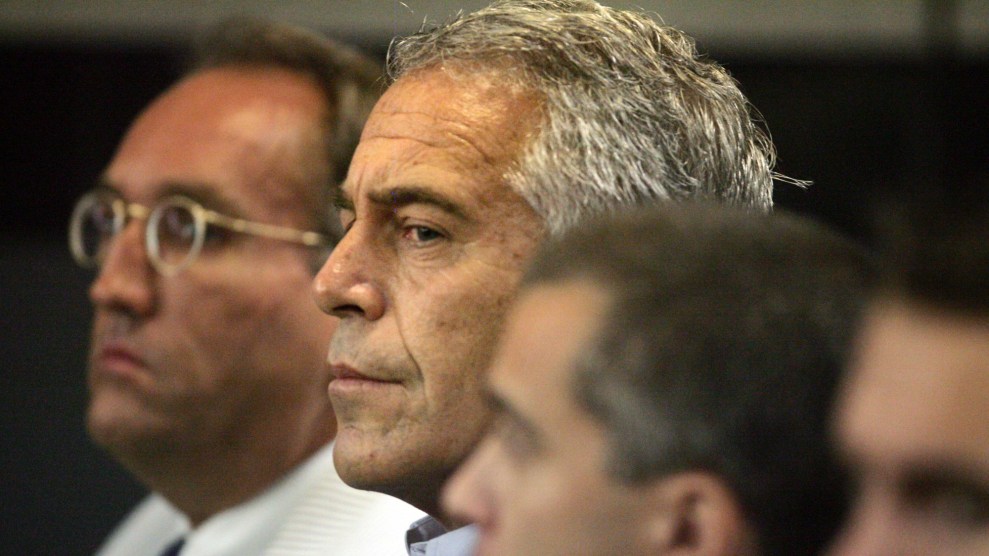

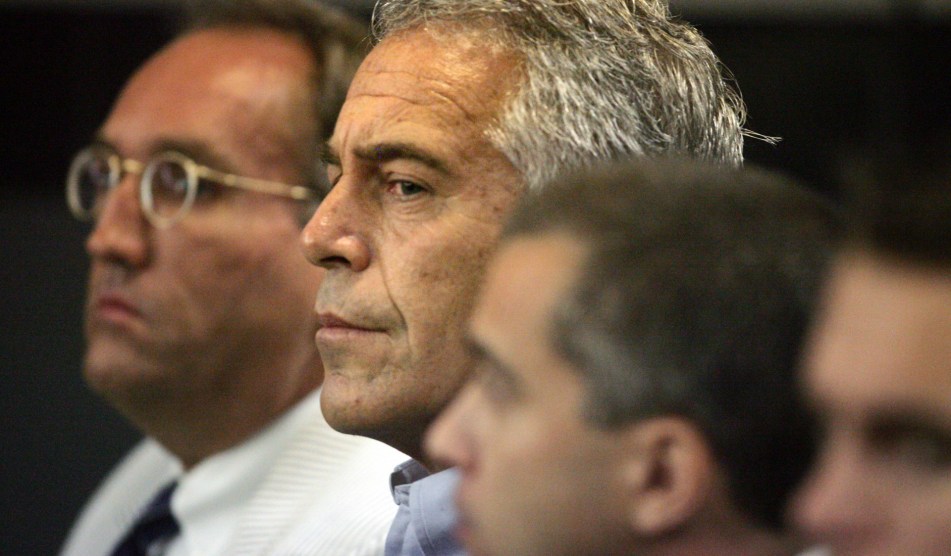

Uma Sanghvi/Palm Beach Post via AP

More than a week after Jeffrey Epstein’s shocking death, which on Friday the New York City medical examiner concluded was a suicide by hanging, it still feels somewhat unbelievable. Even if you’re not in the camp of Trumpian conspiracies, there are a slew of legitimate questions about the the negligence (or worse) on the part of the staff guarding Epstein at Manhattan’s Metropolitan Correctional Center. (The financier had been on suicide watch not long before his death, and there have been credible reports of absentee guards suspected of falsifying duty logs.) Why, for instance, was he not put under extra-close supervision given his high profile, the even-higher stakes, and the damning developments in his case? Ultimately, could his death really be as simple as suicide enabled by staff ineptitude?

The answer is yes—while hard to imagine, it’s definitely possible, according to Christine Tartaro, co-author of Suicide and Self-Harm in Prisons and Jails and a professor of criminal justice at Stockton University. Part of the reason people seem so dumbfounded at his death, she says, is that many Americans have little awareness of a widespread crisis in correctional facilities across the country, in which there are hundreds of suicides every year. And while Epstein is the most high-profile individual Tartaro can think of to die in jail awaiting trial, he is not the only one. She notes that a determined individual could find a way to make it happen, particularly given the dire circumstances in many of the facilities.

“Somebody walked up to me yesterday and said, ‘Did you hear he was murdered?'” Tartaro says. “I think we need to just take a deep breath and wait.”

Here are a few of the key takeaways from our recent conversation:

A lot can happen when the guard isn’t looking—even in just a few minutes

The fact that Epstein was no longer on suicide watch when he died has justifiably drawn loud criticism, but even if he had been, as my colleague Dan Spinelli reports, it wouldn’t necessarily have saved him.

Tartaro echoes this point. “Some suicide watches will use 15-minute supervision intervals,” she says. “Well, it’s possible to pull off a suicide attempt in less than 15 minutes.” Someone who is committed can break up the process, making a noose between inspections one time, for instance, and affixing it during the next interval, she says. Given that the guards in Epstein’s case were reportedly asleep and didn’t check on him for hours, he certainly would have had the time.

Suspicious deaths have happened in jail before

Usually, deaths in custody don’t trigger waves of conspiracy theories and public scrutiny, but one exception, Tartaro notes, is the 2015 case of Sandra Bland, the civil rights activist who was found dead in her jail cell after police took her into custody during a traffic stop. Many didn’t believe Bland would have killed herself over a traffic arrest, and some suggested Bland was killed by police before they even brought her to the jail. The media further fueled some of the more outrageous conspiracy theories. Though there has been no evidence of such foul play (the autopsy in Bland’s death officially declared it a suicide), the incident raised legitimate questions about police discrimination and violence and why she was arrested in the first place. (Footage of the incident, filmed by Bland in her car and released just this May, has renewed calls for an investigation into her arrest.)

In a somewhat similar fashion, reporting last week suggested initial autopsy findings in Epstein’s case could point to homicide due to a broken hyoid bone, further sparking outcry and intrigue. Tartaro notes that the claim was perhaps overhyped, as the broken bone is not uncommon in suicides, especially in older victims; the medical examiner ruled the death a suicide the next day.

Then there’s the 2008 case of a young man found dead in jail pre-trial after allegedly killing a cop during a car chase in Prince George’s County, Maryland. At first authorities thought his death was a suicide by hanging, but medical examiners then declared the death a homicide. A guard with access to the victim’s cell was found to have given conflicting reports on what happened. After an extensive investigation failed to determine the cause of death, the guard served time for obstructing justice.

Tartaro also points to a high-profile case from New Jersey last year, in which a doctor, James Kauffman, killed himself in his cell while awaiting trial for his wife’s murder. He had allegedly hired a hitman because he feared she would expose the pharmaceutical drug ring he was running with the Pagan motorcycle gang. Some speculated his death could make it harder to prosecute the other people involved. Investigators uncovered a plot to have Kauffman killed in jail, and for his safety he was moved to another facility where he then killed himself (and was the fifth inmate to die at the jail in eight months).

But even suspicious deaths almost never remain unresolved

Despite the case in Prince George’s County, ultimately, “there are very few situations where it’s unresolved in terms of exactly how a person dies,” Tartaro says. “The majority of these deaths that appear to be suicides are suicides.”

Resolving the remaining questions about Epstein’s death will likely hinge on video surveillance of the area inside the jail and further investigation into the staff logs, according to Tartaro. Though there is supposedly no footage of the inside of Epstein’s cell, there should be video covering the area of the facility where he was held.

“The two things that immediately came to mind when I heard about this and heard people questioning what happened was: One, the video surveillance, which would be the best indicator of what truly happened. Were there people entering or exiting the cells?” Tartaro asks. Video surveillance is often crucial in exposing the true roots of violent incidents within opaque prison and jail systems. In April, for instance, video surveillance was the key to determining how violent assaults on guards and prisoners in an Arizona prison were possible. (The locking mechanisms on the cell doors were actually broken.)

The other key piece in the puzzle should be guard logs, since “officers need to log all of their movements in all of their interactions with other inmates,” Tartaro says. “Unfortunately, I am reading reports that there’s a suggestion that the officers went back after the suicide to alter the logs.”

Chronic understaffing and prisoner overcrowding certainly make deaths more likely

According to reporting, the guards charged with watching Epstein were working overtime, one of them for at least four days. And one of the guards wasn’t even a full-time correctional officer. These circumstances aren’t unusual at this or other federal institutions; as Mother Jones reported last year, teachers, nurses, and accountants with minimal training have been standing in as substitute guards at understaffed federal correctional facilities due to budget cuts and a hiring freeze. On the night of Epstein’s death, the Metropolitan Correctional Center reportedly had only 18 guards watching over roughly 750 prisoners.

Training to recognize signs of mental illness and suicide ideation and what to do with that information is woefully lacking, as is funding for mental health professionals in jails and prisons. “There has to be clear protocol as to whose responsibility it is to do everything every step of the way,” Tartaro says. This has become an increasingly urgent gap as United States “corrections facilities now are, by default, the largest mental health facilities in the nation,” she notes.

This contributes to an environment in which suicides are rampant, though the deaths “rarely get much scrutiny or media attention,” she says. “Most of these suicides involve somebody who is poor, mentally ill, addicted to drugs, and just kind of falls through the cracks. And then there isn’t that much scrutiny in the aftermath.”

Still, we’ll need to wait for final answers in the Epstein case

“People find it inconceivable that he was actually left alone. Everybody looks at him and sees a pretty obvious threat for suicide or a homicide,” Tartaro says. “He had reason, you know, good motivation to want to end his life. He was a billionaire who owned his own island and now was living in a probably 6-by-12 jail cell. He knew that the public pressure was on so this time he was not going to be able to get a sweetheart deal. People who are facing long prison sentences are at higher risk for suicide.” But also, she notes, “it could benefit other people—and some very powerful people—if he died, so there is some possibility…There was definitely a good motive for homicide as well.”

There is certainly a need for further investigation into how Epstein’s death was allowed to happen and into how dismal jail conditions are across the country. If the public frenzy and speculation surrounding Epstein are good for anything, Tartaro argues: “It does a little bit of good in that it keeps the pressure on the government to actually conduct an investigation.” She adds, “On the other hand, I don’t think that hysteria and conspiracy theories are particularly helpful, especially in this era, where we have so many arguments about what’s fake news and what’s real news. We need to be cautious and not jump to conclusions.”