<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-114467512/stock-photo-hollywood-california-september-the-world-famous-landmark-hollywood-sign-on-september.html?src=hBaRLG-Vv40avgfLhK-UFg-1-0">Konstantin Sutyagin,</a>/Shutterstock

This story was produced and originally published by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration. Subscribe to the podcast and learn more at revealnews.org.

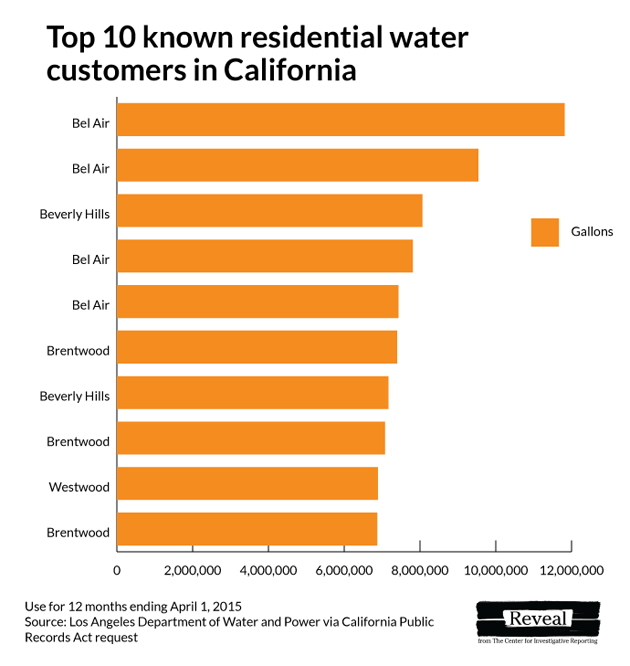

In the midst of a searing drought, one home in West Los Angeles’ exclusive Bel Air neighborhood used an astonishing 11.8 million gallons of water in one year—enough for 90 households.

A lushly landscaped, mansion-studded enclave of wealth and celebrity, Bel Air has been home to Michael Jackson, Jennifer Aniston and even former President Ronald Reagan.

Now, according to records obtained by Reveal, Bel Air has another distinction: Its 90077 ZIP code is also home to the biggest known residential water customer in California.

The city of Los Angeles won’t identify this 11.8 million-gallon user, whose water bill for the 12 months ending April 1 likely topped $90,000, according to the Department of Water and Power’s rate structure.

Nor has the city taken any steps to stop this customer—or scores of other mega-users—from pumping enormous quantities of water during a statewide crisis now in its fourth year.

It’s the same story throughout urban California.

Despite the drought, well-heeled residential customers in affluent neighborhoods are being allowed to use as much water as they want to buy, according to a review of utility records from the state’s biggest urban water agencies.

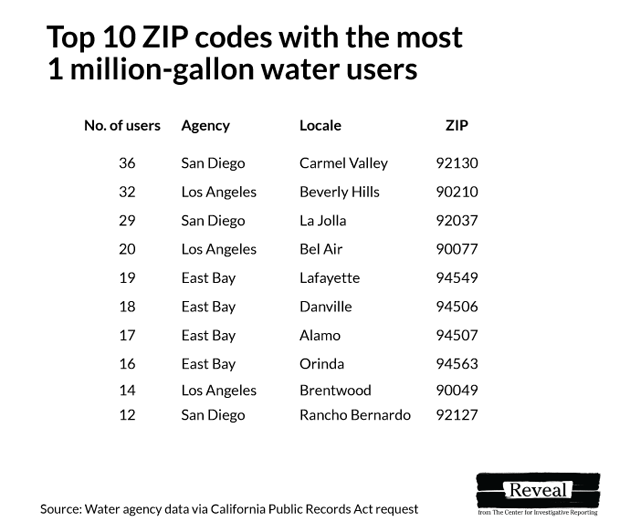

In all, 365 California households pumped more than 1 million gallons of water apiece during the year ending in April, the records show.

One million gallons is enough for eight families for a year, according to a 2011 state estimate, and many of California’;s mega-users pumped far more than that. Of the total, 73 homes used more than 3 million gallons apiece, and another 14 used more than 6 million.

These mega-users live in San Diego’s posh La Jolla beachfront community, in affluent suburbs of Contra Costa County in the Bay Area and especially in Los Angeles’ wealthy neighborhoods.

In addition to the state’s biggest user, Bel Air had 19 customers pumping more than 2.8 million gallons per year. In nearby Beverly Hills, the famously upscale ZIP code of 90210 had 32 customers using 2.8 million gallons or more.

The names of all these mega-users are secret. Los Angeles and all of the state’s other major water agencies declined to name any of their big guzzlers, saying that identifying a customer—even one using extraordinary amounts of water—would raise privacy concerns.

Reveal’s findings of wanton water use during the drought are “absolutely shocking,” said Tracy Quinn, a water policy analyst for the Natural Resources Defense Council in Santa Monica.

“Looking at the list that you’ve provided…I’m actually shocked by the amount of water that can be used in a single-family residence,” she said in an interview. “It’s appalling.”

While the water flows to the mega-users, the state’s urban water agencies have mounted a furious public relations campaign to persuade the public to cut water use in response to what they call “the drought of the century.”

In a barrage of public service broadcasts, emails and fliers, Californians have been urged to rip out their lawns, stop washing their cars and even limit their toilet flushing to save water. The conservation campaign has been pronounced a success: In August, the state said urban customers had cut their use by 31 percent.

But the agencies have shown little enthusiasm for restricting use by high-end customers who are consuming huge amounts of water. Only recently did two agencies—one in Oakland, the other east of Los Angeles in the Coachella Valley—begin imposing penalties on mega-users. Other agencies haven’t followed suit.

Instead, the agencies have fined hundreds of Californians for offenses such as hosing down their driveways or failing to replace broken sprinkler heads.

David Wilson, a homeowner in Los Angeles’ Mid-Wilshire neighborhood, got slapped with $600 in fines for watering on the wrong day of the week and letting runoff flow into the street. He blamed a sprinkler malfunction.

Wilson thought the fines were excessive, and he said he was shocked to learn that the city was publicizing his name and address because of the violation.

When a reporter showed him a list of mega-users, with names withheld by the city to protect their privacy, Wilson said, “That’s asinine. These are the people that people should be going after.”

Looking at the top user on the list, Wilson asked, “Is this 11 million gallons? How do they even do that?”

Drought or no, simply using a lot of water can’t get you in trouble in LA

As long as Angelenos follow the other usage rules, they can pump as much water as they can pay for, said Martin Adams, senior assistant general manager for the water system at the Department of Water and Power.

“There’s no ordinance on the books in Los Angeles to go after an individual customer strictly for their use,” he said in an interview.

In a follow-up email, he suggested that concerns about mega-users were overblown, noting that the city’s top 100 residential customers account for only about two-tenths of 1 percent of LA’s total usage.

“This underscores the importance of focusing on water conservation citywide,” he wrote.

But other considerations come into play when a conservation program is based on voluntary compliance, noted Jack Humphreville, who monitors water issues for The Greater Wilshire Neighborhood Council civic group.

“Are you sending the right message if some S.O.B. is out there using 11 million gallons?” he asked.

Keith Warner, a Franciscan friar and ethicist at Santa Clara University, said water agencies have an obligation to make sure all Californians share the burden of conservation during the drought.

“It’s ethically problematic” to do otherwise, he said.

Of course, residential water use forms only part of the conservation picture during California’s drought; the state’s agriculture industry uses four times as much water as its cities and towns.

For this story, Reveal set out to identify the top 100 residential customers at the state’s biggest public water agencies. All the agencies resisted providing the information.

For decades, utility data was a matter of public record in California. During a 1991 drought, an Oakland Tribune news story that identified water wasters by name caused an outcry.

In the end, the biggest water users were forced to reduce their use by 20 percent or the East Bay Municipal Utility District threatened to limit the flow of water to their homes.

But in 1997, the Legislature weakened the state’s Public Records Act and gave utilities the legal right to keep customers’ names and usage a secret. The measure was pushed by the city of Palo Alto, citing the privacy concerns of Silicon Valley executives. Still, the revised law said utilities could reveal this information if they determined that disclosure was in the public interest.

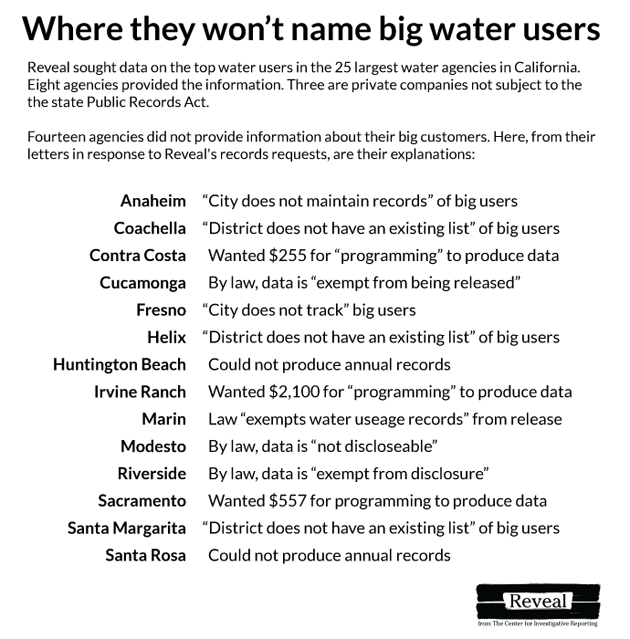

Earlier this year, Reveal asked California’s 22 largest public water agencies to identify their 100 biggest customers for the 12 months ending April 1, arguing that the public has a right to know about water use during a statewide emergency.

All refused.

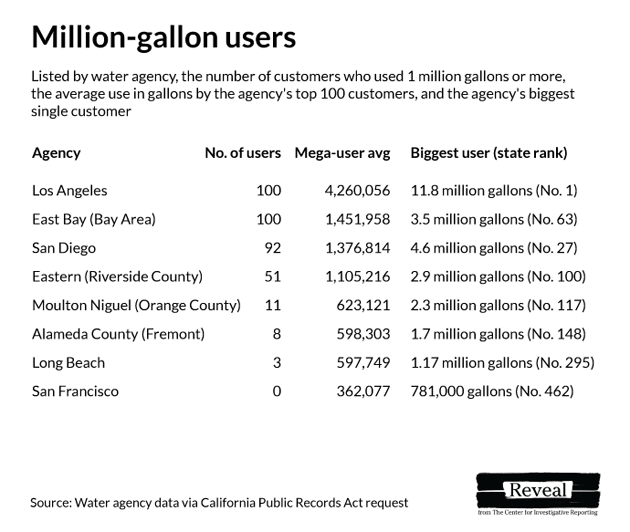

But eight big districts—including Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco—agreed to provide usage data after deleting customers’ names and addresses. Three also identified the ZIP codes where their biggest users reside.

But 14 agencies, including Sacramento, Fresno and Modesto, refused to give any information at all.

Some contended that the law doesn’t require them to provide data about customers’ water use. Others said they didn’t keep track of consumption by their biggest customers—a remarkable assertion in the middle of a drought.

Silicon Valley’s water data also was unavailable because the San Jose Water Co. is a private company, and thus not subject to open records laws. But the data Reveal acquired showed that the mega-users were clustered in some of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the state. Here are the details by region:

Los Angeles

In August, Mayor Eric Garcetti said LA’s water use had dropped by 21 percent during two years of drought.

But the city also has 92 of the top 100 residential water users known in California. On average, LA’s mega-users pumped 4.2 million gallons per year apiece. The mega-users live in neighborhoods favored by the rich and famous.

The towering green hedges that line the winding streets of Bel Air screen the expansive homes of actors, film executives and a host of entertainment lawyers, real estate developers and plastic surgeons.

Also living in Bel Air: not just the state’s biggest known water customer, but four of California’s top five, with usage ranging from 7.4 million to 11.8 million gallons per year.

Another pocket of mega-users was in Beverly Hills’ 90210 ZIP code, namesake of the 1990s television series about the problems of the young and wealthy. It’s home to actor Tom Cruise, soccer legend David Beckham and corporate farmer Stewart Resnick, who owns more than 100,000 acres of heavily irrigated orchards in the Central Valley.

Also residing in 90210: The third-biggest water user identified in the state. At 8 million gallons per year, the customer used water for about 60 families.

Yet another concentration of mega-users was in Brentwood. The sixth-biggest known water user in the state (7.39 million gallons, which is enough for 56 families) also lives in Brentwood, along with 13 other residents who used 2.9 million gallons or more.

San Francisco Bay Area

Oakland’s East Bay Municipal Utility District says it has begun assessing “excessive use penalties” on customers who pump at a rate of more than 359,000 gallons per year.

In the meantime, the agency’s 100 biggest customers all used at least 1 million gallons apiece. Most live in the Contra Costa County suburbs: 18 in the exclusive Blackhawk subdivision, 17 in upscale Alamo.

The district’s biggest single user pumped 3.5 million gallons in a year. This customer lives in an unincorporated area near the Diablo Country Club, where some properties have vineyards or orchards. Nine other customers in Diablo used 1.1 million gallons or more.

Utility district board member Doug Linney wanted to know more about the mega-users.

“I don’t know if they have a private golf course in their backyard or what, but it is a lot of water,” he said in an interview. “It certainly seems like it would warrant an investigation to send our team out there.”

Fremont’s Alameda County Water District had eight million-gallon customers – the biggest used 1.7 million. But in cool, foggy San Francisco, there were no million-gallon users at all. The biggest user pumped 781,000 gallons, enough for six families.

San Diego

The city’s biggest user, at 4.6 million gallons, lives in La Jolla, the beach town where former Republican presidential candidates Mitt Romney and John McCain keep homes. Two other La Jolla residents used 4.5 million gallons, and 29 topped the 1 million-gallon mark. Carmel Valley, a sprawling community north of downtown, had 36 customers who used 1 million gallons or more.