A trio of researchers from the University of Missouri and the University of Iowa have a new paper out that calls into question the correlation between lead emissions and violent crime rates. I want to comment on it, but with two caveats:

- I’m not knowledgeable enough to judge the analysis in detail. I can explain what the authors have done, and I can point out some questions, but that’s about it. Serious critiques will have to come from qualified researchers.

- This post isn’t hard to follow, but it’s pretty long and the payback is slim. For that reason, I’m putting it under the fold. Click if you want to wade through the whole thing.

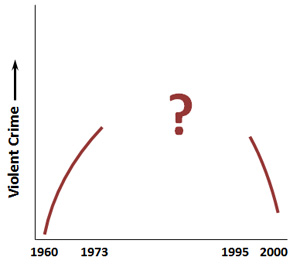

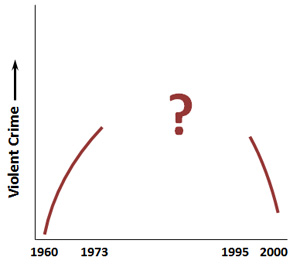

With that out of the way, here’s a rough sketch of the issue. There’s broad agreement about what happened to violent crime in the 60s (it went up dramatically) and the 90s (it went down dramatically). The stylized chart on the right shows this. The question is: what happened in between?

With that out of the way, here’s a rough sketch of the issue. There’s broad agreement about what happened to violent crime in the 60s (it went up dramatically) and the 90s (it went down dramatically). The stylized chart on the right shows this. The question is: what happened in between?

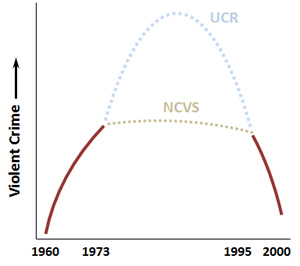

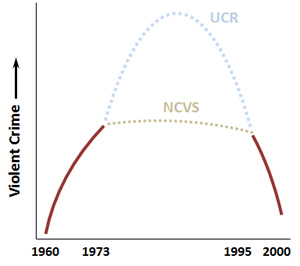

The problem is that there are two sources of data on violent crime (murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault). The first is the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR), which depends on reports from police departments around the country. The nice thing about the UCR is that it goes back a long way and the data is broken down by city. The bad thing about the UCR is that it can show spurious trends if police departments report crimes differently over time.

This is especially a problem with rape and aggravated assault. In the case of rape, we know that women became more likely to report rape over the past 50 years, and we also know that police departments took rape reports more seriously. So even if rape rates hadn’t changed at all, we’d probably still see an increase in the numbers.

In the case of aggravated assault, there’s no firm rule for what makes an assault “aggravated.” So it’s possible that the UCR numbers might be tainted simply because police departments have changed their standards for what counts as aggravated assault. This is a potentially serious problem since aggravated assault is one of the biggest components of overall violent crime rates.

So that’s the UCR. The second source of crime data is the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), which relies on interviews with families to ask them if they’ve been victims of a crime. The nice thing about the NCVS is that it gets  around the police reporting problem. The bad thing about the NCVS is that (a) it only goes back to 1973, and (b) surveys can have methodology problems too. In particular, there were several criticisms of the original NCVS that were addressed in a redesign that started up in 1993. So there are some known issues in the period from 1973-93.

around the police reporting problem. The bad thing about the NCVS is that (a) it only goes back to 1973, and (b) surveys can have methodology problems too. In particular, there were several criticisms of the original NCVS that were addressed in a redesign that started up in 1993. So there are some known issues in the period from 1973-93.

Why does this matter? Because when I fill in the chart with data from 1973-95, it looks way different depending on which source you use. According to the UCR, violent crime kept going up all through the 80s, reaching a peak in 1991. According to the NCVS, violent crime was declining modestly during this entire period.

So which one is more accurate? There’s no way to know for sure, but the authors of the paper use the following methodology to arrive at a good guess:

- Take a look at the murder rate. The nice thing about murder (from a reporting standpoint) is that it’s almost always reported and it’s almost always clear cut. If you have a dead guy and it’s not a suicide, then it’s a murder. For that reason, everyone agrees on the murder rate.

- Make an assumption that murder and other violent crimes should follow a roughly similar pattern.

- Run the numbers to see which crime source correlates best with the murder rate. The authors conclude that NCVS correlates better and is therefore probably more accurate.

- Check to see if various theories of crime fit the NCVS data. The authors conclude that the lead hypothesis doesn’t. It fits the UCR data well, but not the NCVS data.

I have a few comments about this study, but I want to emphasize again that I’m a layman. These aren’t serious methodological critiques. They’re just observations that I hope others will pick up on and look into. That said, here they are:

- Can it really be true that violent crime was declining between 1973-91? There’s no question that this is what the NCVS data tells us, but it sure doesn’t match what everyone thought was going on at the time. By the early 90s, virtually everyone in America was convinced that (a) crime had been rising relentlessly for decades and (b) it would continue rising. (Remember “superpredators”?) At a purely gut level, a crime decline during this period sure doesn’t feel right.

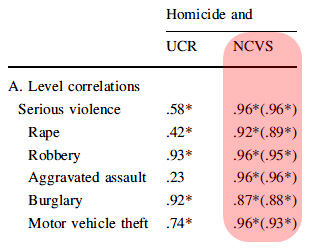

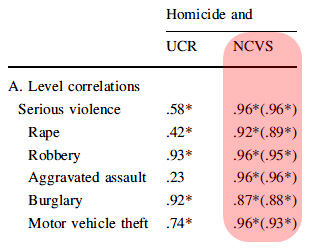

The correlations of murder and violent crime in the authors’ version of NCVS data seem almost too good to be true (see table on right). Every single one is above 0.87 and some are close to 1. Does it really make sense that murder should be almost perfectly correlated with motor vehicle theft?

The correlations of murder and violent crime in the authors’ version of NCVS data seem almost too good to be true (see table on right). Every single one is above 0.87 and some are close to 1. Does it really make sense that murder should be almost perfectly correlated with motor vehicle theft?- On a related note, the authors’ estimate of the correlation of gasoline lead with violent crime is shockingly low: zero. At the very least, we know that both series show a dramatic decline during the 90s, which is a third of the period under investigation. It’s surprising that there isn’t at least a small correlation even with the NCVS data.

- The lead-crime correlation only works for the entire period from approximately 1950 to 2000. If you pick out a subsection of that period, it’s not surprising that you might lose the signal. That’s especially true when you choose the middle of the period, a time when lots of cohorts all had extremely elevated lead levels. With levels that high among a broad swath of the population, it’s entirely possible that other factors were temporarily more important. (Just as they are now, when lead levels are low across the board.)

- For what it’s worth, I got lots of critiques of my 2013 article on lead and crime, but no one ever suggested that using UCR data was a problem.

One final note. If I had one thing to do over in my 2013 article, I think I’d dump the chart showing the overall national correlation between lead and crime (the subject of this paper). It’s obvious why it was included: it’s a visually dramatic statement, and historically speaking it was the observation that started research into lead and crime. But there’s a reason I wrote my  piece in 2013: that was when the evidence started really piling up in favor of the lead theory. The national correlation by itself would never have been enough to justify writing the piece. In fact, it’s easily the least important part of the whole argument, and placing it front and center did nothing except prompt endless choruses of “correlation is not causation!” from people who don’t read beyond the pictures. I wish I’d never included it.

piece in 2013: that was when the evidence started really piling up in favor of the lead theory. The national correlation by itself would never have been enough to justify writing the piece. In fact, it’s easily the least important part of the whole argument, and placing it front and center did nothing except prompt endless choruses of “correlation is not causation!” from people who don’t read beyond the pictures. I wish I’d never included it.

So what is important? On a statistical level, there are state-level correlations, city-level correlations, and, most importantly, international correlations. All of those together paint a very convincing picture. On an outcome level, there are prospective studies that track children with elevated lead levels. All of them show that they get arrested at higher rates the higher their childhood lead exposure. On a medical level, there are now brain scan studies that provide a plausible pathway for lead exposure to cause permanent neurological damage to parts of the prefrontal cortex associated with impulse control.

So that’s that. I have questions about this study, but I don’t have the chops to provide any answers. Hopefully other researchers will comment on this paper and eventually guide us to some firmer conclusions.

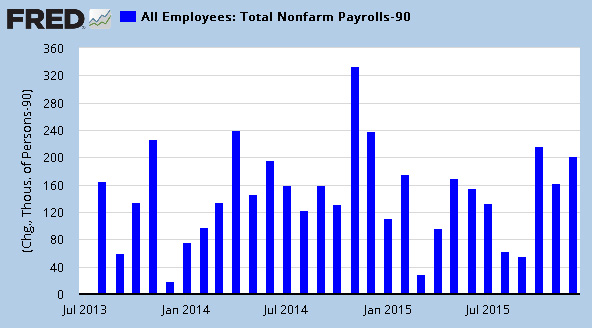

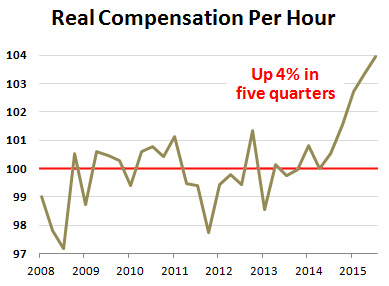

Unemployment is relatively low, but thanks to modest GDP growth and the long-term unemployed continuing to re-enter the workforce, the labor market hasn’t been tight enough to push wages up.

Unemployment is relatively low, but thanks to modest GDP growth and the long-term unemployed continuing to re-enter the workforce, the labor market hasn’t been tight enough to push wages up.

With that out of the way, here’s a rough sketch of the issue. There’s broad agreement about what happened to violent crime in the 60s (it went up dramatically) and the 90s (it went down dramatically). The stylized chart on the right shows this. The question is: what happened in between?

With that out of the way, here’s a rough sketch of the issue. There’s broad agreement about what happened to violent crime in the 60s (it went up dramatically) and the 90s (it went down dramatically). The stylized chart on the right shows this. The question is: what happened in between? around the police reporting problem. The bad thing about the NCVS is that (a) it only goes back to 1973, and (b) surveys can have methodology problems too. In particular, there were several criticisms of the original NCVS that were addressed in a redesign that started up in 1993. So there are some known issues in the period from 1973-93.

around the police reporting problem. The bad thing about the NCVS is that (a) it only goes back to 1973, and (b) surveys can have methodology problems too. In particular, there were several criticisms of the original NCVS that were addressed in a redesign that started up in 1993. So there are some known issues in the period from 1973-93. The correlations of murder and violent crime in the authors’ version of NCVS data seem almost too good to be true (see table on right). Every single one is above 0.87 and some are close to 1. Does it really make sense that murder should be almost perfectly correlated with motor vehicle theft?

The correlations of murder and violent crime in the authors’ version of NCVS data seem almost too good to be true (see table on right). Every single one is above 0.87 and some are close to 1. Does it really make sense that murder should be almost perfectly correlated with motor vehicle theft? piece in 2013: that was when the evidence started really piling up in favor of the lead theory. The national correlation by itself would never have been enough to justify writing the piece. In fact, it’s easily the least important part of the whole argument, and placing it front and center did nothing except prompt endless choruses of “correlation is not causation!” from people who don’t read beyond the pictures. I wish I’d never included it.

piece in 2013: that was when the evidence started really piling up in favor of the lead theory. The national correlation by itself would never have been enough to justify writing the piece. In fact, it’s easily the least important part of the whole argument, and placing it front and center did nothing except prompt endless choruses of “correlation is not causation!” from people who don’t read beyond the pictures. I wish I’d never included it. become the UnCarrier in the first place?

become the UnCarrier in the first place?

the war on drugs, all at a pretty modest cost.

the war on drugs, all at a pretty modest cost.