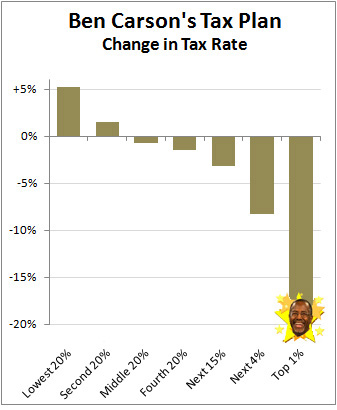

Back in the day—meaning approximately 2008 or so—Republican presidential candidates made a big mistake. They released their tax plans without bothering to figure out anything other than the average tax cut each one provided. The frequent result was that taxes went up on the poorest people and down on the richest. That’s bad optics.

By 2012 they’d all wised up. Their tax cuts might be bigger for the rich, but they made sure everyone got a cut.

When I was looking at Ben Carson’s plan last night, I realized that the poor guy hadn’t been paying attention. He figured that by setting a zero percent tax rate on income up to $36,000, he’d be guaranteeing that the poor would get a tax cut. Unfortunately, his actual knowledge of the tax code is so shallow that he didn’t realize what he meant when he said his plan eliminated all credits  and deductions. That means he’s getting rid of the Earned Income Tax Credit, which often amounts to a negative tax rate for the poor. In other words, paying $0 is a tax increase for a lot of them. Citizens for Tax Justice provides the details:

and deductions. That means he’s getting rid of the Earned Income Tax Credit, which often amounts to a negative tax rate for the poor. In other words, paying $0 is a tax increase for a lot of them. Citizens for Tax Justice provides the details:

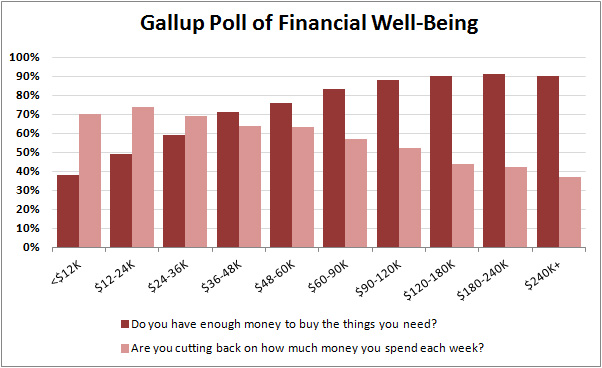

Under Carson’s plan, the bottom 20 percent of taxpayers would receive an average annual tax increase of $792 and the second 20 percent would get an average annual tax increase of $447, while the top one percent would receive an average annual tax cut of $348,434. The main reason Carson’s plan would increase taxes on low-income families is that it would eliminate all tax credits, including the highly effective Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC).

There’s still no reason to care about this since Carson is obviously doomed to return to the book promotion racket at this point. Still, just for the record, I figure this deserves a chart to memorialize it for posterity. So here it is.

Here’s what I see: a complacency among the generation of young women whose entire lives have been lived after Roe v. Wade was decided.

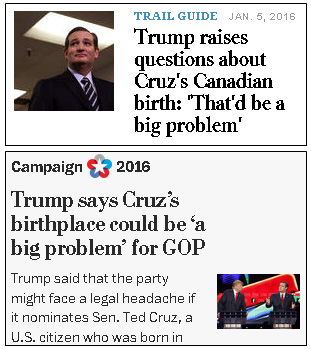

Here’s what I see: a complacency among the generation of young women whose entire lives have been lived after Roe v. Wade was decided. Stop it, stop it, stop it, STOP IT! Just because Donald Trump says something calculatingly stupid and provocative doesn’t mean it has to be reported as front-page news. Everyone knows that his “Cruz is a Canadian” thing is ridiculous—and he wouldn’t bother saying it if he didn’t know that it was going to get loudly amplified by a media that just can’t say no to him.

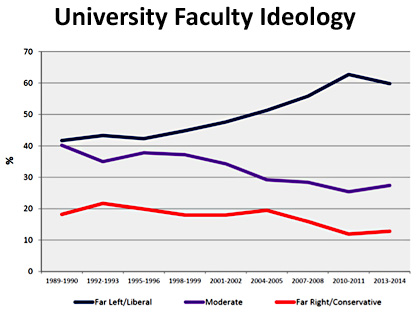

Stop it, stop it, stop it, STOP IT! Just because Donald Trump says something calculatingly stupid and provocative doesn’t mean it has to be reported as front-page news. Everyone knows that his “Cruz is a Canadian” thing is ridiculous—and he wouldn’t bother saying it if he didn’t know that it was going to get loudly amplified by a media that just can’t say no to him. become almost entirely liberal. And this is for all university faculty.

become almost entirely liberal. And this is for all university faculty.  Farhad Manjoo is trying hard to dredge some kind of story out of

Farhad Manjoo is trying hard to dredge some kind of story out of  More interesting is what this says about relations between North Korea and China. Short answer:

More interesting is what this says about relations between North Korea and China. Short answer:  It sounds pretty serious, no?

It sounds pretty serious, no?

Today’s test: one of these men is an illustration from a Nazi propaganda poster. The other is the president of the United States. Can you tell which is which?

Today’s test: one of these men is an illustration from a Nazi propaganda poster. The other is the president of the United States. Can you tell which is which?