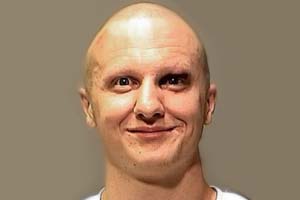

Pima County Sheriff's Office

Guest blogger Beth Winegarner writes about teens, culture, and music.

In one of a handful of videos Jared Lee Loughner posted on YouTube, a man cloaked in brown burns the American flag while Drowning Pool’s “Bodies” blares in the background. As reporters pull together descriptions of the man who shot and killed six people and wounded 14 others, including Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, it’s not surprising that many mention which band Loughner picked as his soundtrack. What is surprising is that most reporters aren’t blaming Loughner’s taste in music for the attack.

“Since Columbine, much has changed,” Los Angeles Times pop critic Ann Powers tweeted Saturday night. “Then, the focus may have been on Jared Lee Loughner’s past as a rocker. Music no longer embodies menace. Other demons/scapegoats do.”

Instead, the media’s focus on 22-year-old Loughner’s mental instability implies a painful double-standard in how such sprees are covered. When shooters are children, cultural interests—such as video games, goth, or heavy-metal music—are cited as causal factors, which distracts from any underlying mental illness. But when mass killers reach the age of adulthood, media focus frequently turns to untreated mental-health issues. As a nation, perhaps we’re just not ready to admit that some teens are in serious mental trouble.

In the hours following the Columbine High School shootings, reporters around the world lit upon the notion that Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold’s interest in angry music and violent video games must have prompted their killing spree. And after some classmates (and teens pretending to be classmates) claimed that the shooters were Marilyn Manson fans, the musician himself became a media target. Photos of Manson decorated a new National School Safety Center-issued checklist of “danger signs” that a teen might be about to bring a gun to class. (Some danger signs: mood swings, cursing, and antisocial behavior.) Kansas Sen. Samuel Brownback even wrote a letter to Seagram’s—the owner of Manson’s record label—requesting that the corporation “cease and desist profiteering from peddling violence to young people,” and drop the band from its roster.

Years later, after painstakingly combing through Harris’ and Klebold’s journals, academic and personal histories, and behavior patterns, Columbine author Dave Cullen found more likely motivations for the massacre that the teens had spent months planning. Cullen concluded that Harris was a psychopath, while Klebold was a depressive who romanticized suicidal figures.

Despite Powers’ comment, the age-based reporting double standard hasn’t changed drastically since 1999.

In March 2005, when 16-year-old Jeffrey James “Jeff” Weise went on a killing spree in Red Lake, Minnesota, he took nine lives and wounded five other people before killing himself. He had a history of creating disturbing art pieces—and attempting suicide at least once—but media reports focused on his black trench coat and “obsessive” interest in Horrorcore rapper Mars.

Meanwhile, when Seung-Hi Cho, 23, killed 32 people at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in April 2007, there was nary a mention of his hobbies or personal interests. Not only were Cho’s favorite songs not blamed for his killing spree, we don’t even know what they were. Instead reporters dutifully detailed Cho’s mental health history, including a 2005 evaluation in which he was found “mentally ill and in need of hospitalization.”

It’s not as though the Virginia Tech story changed how journalists report on mass shootings. In October of that same year, Pekka-Eric Auvinen, 18, shot and killed eight people at Jokela High School in Jokela, Finland before ending his own life. He was prescribed antidepressants in the year before the murder-suicide, but reporters still made plenty of the fact that he used KMFDM’s “Stray Bullet” as background music for a YouTube video announcing his plans to attack the school. After all, it was a song Eric Harris apparently also liked. (Despite the title, the song is about ideas that cause sudden, radical shifts in belief.)

Media coverage improved slightly in 2009 after Tim Kretschmer, 17, shot and killed 15 people in southwestern Germany. While reports noted that Kretschmer was an avid player of the first-person shooter Counter Strike, one commentator also noted that “game addiction is a symptom of something wrong, and not a cause.” And there was something wrong with Kretschmer—in the year before his spree he was in and out of psychiatric hospitals, undergoing treatment for depression, anger, and violent urges.

Journalists include these details because readers are often hungry to know more about these boys who commit unthinkable acts of violence. But these same points can create the dangerous impression that shooters’ media interests somehow led them to pull the trigger. Worse, they distract readers from the very real problems these young men faced: extreme rage, suicide attempts, and untreated mental illness.

Why, as a culture, do we insist on ignoring the mental-health issues at work in our teen population? Are we unable to admit that teens are capable of suffering the same yawning mental abysses (or, worse, the chilling sociopathy) that often fuels adult rampages?

When we hold teen and adult shooting sprees side-by-side, we can see a pattern of instability in both populations. Perhaps society could learn to intervene before troubled boys become gun-toting, politically charged conspiracy theorists.