Passed in 1994, California’s “three strikes” law is the nation’s harshest sentencing law. Designed to imprison for life anyone who commits three violent crimes, the law has inadvertently resulted in the incarceration of a lot relatively harmless people, for a long time and at great public expense. Crimes that have earned people life sentences: Stealing a dollar in loose change from a car, breaking into a soup kitchen to steal food, stealing a jack from the open window of a tow truck, and even stealing two pairs of children’s shoes from Ross Dress for Less. The law is one reason that California’s prison system is dangerously, and unconstitutionally, overcrowded. More than 4,000 people in the prison system are serving life sentences for non-violent crimes.

In 2012, with corrections costs consuming ever more of the state budget, the voters in the state had had enough, and they approved a reform measure that would spring many of these low-level offenders from a lifetime of costly confinement. By August of last year, more than 1,000 inmates had their life sentences changed and were released; recidivisim rates for this group has also been extremely low. But further progress in the reform effort is being stymied by one thorny problem: Nearly half of the inmates serving time in California prisons suffer from a serious mental illness such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. So far, judges have been reluctant to let these folks out of their life sentences.

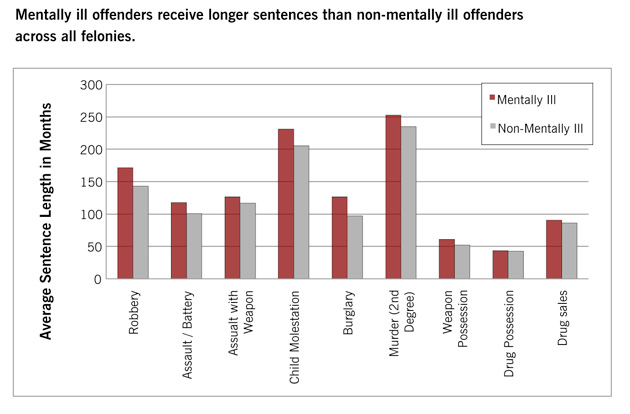

A new report from Stanford Law School’s Three Strikes project notes that the number of mentally ill prisoners denied relief from a life sentence is three times larger than those without a brain disease. The disparity largely stems from the fact that judges and juries tend to give people with brain diseases much harsher sentences to begin with.

Once in prison, their illnesses go untreated, and the prison conditions exacerbate their behavioral symptoms. As a result, they are at greater risk of getting in trouble for breaking prison rules and being sanctioned with severe disciplinary measures, including solitary confinement—a vicious cycle that can make their symptoms even worse, getting them in even more trouble. A long record of rule-breaking is one thing judges consider when weighing a request to reduce a life sentence under three-strikes reform, and a reason so many mentally ill people have been denied resentencing.

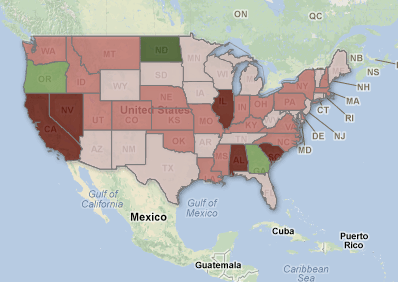

All of these factors are now driving a push in California to work harder to ensure that people with brain diseases don’t end up in the correctional system in the first place. Led by State Senator Darrell Steinberg and Stanford law professors who published the new report, the effort includes a call for more investment in mental health courts that focus on treatment rather than punishment. California currently has 40 such courts in 27 counties, and people like Steinberg think they should be expanded state-wide thanks to their effectiveness and cost-savings.

In 2006, Santa Clara County calculated $20 million in savings from its mental health court’s success in keeping mentally ill people out of prisons. Sacramento County saw the cost of keeping mentally ill people out of traditional courts fall 88 percent thanks to its mental health court. Other research has shown that the specialized courts also keep mentally ill people from cycling back into the justice system. Mentally ill people in Michigan’s mental health courts commit new crimes at a rate 300 percent lower than those who weren’t in those courts.

But money isn’t the only reason Steinberg wants to see mental health courts expanded. He notes in the Stanford report that this new approach “saves lives from being forsaken.” He invokes the moral cost of failing to treat sick people with compassion, and the tragedy of the lost human potential that occurs when the only place for a person with a brain disease today is in a prison.

Watch the video directed by Kelly Duane de la Vega and Kattie Galloway of Loteria Films (above) about the mental health courts that makes his point and shows just how powerful such venues can be in reclaiming lives and helping sick people return to normal functioning in the community.