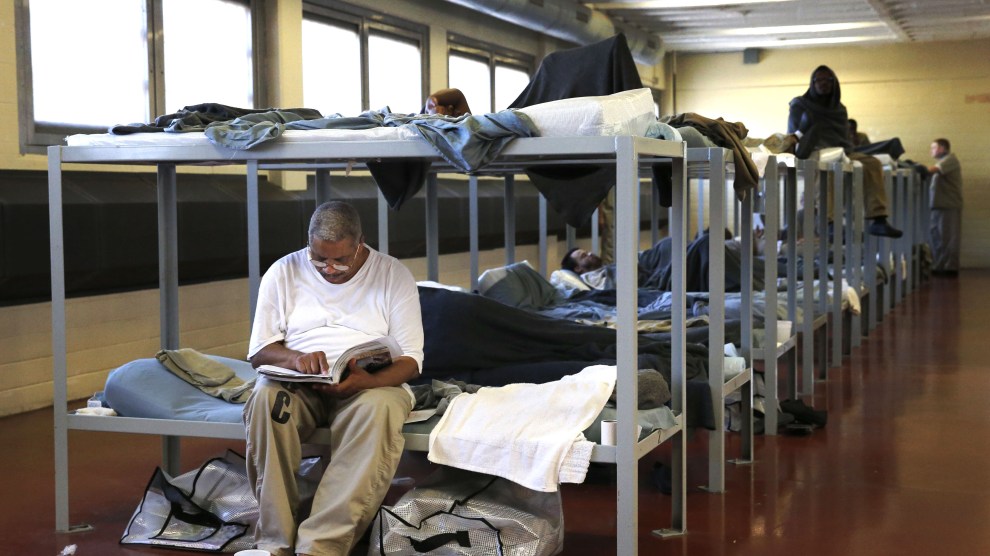

William, a 62-year-old inmate, sits on his bottom bunk and works a word puzzle inside the Cook County Jail's Division 2 Dorm in 2014. Charles Rex Arbogast/AP

Outside Chicago’s Cook County Jail on Tuesday, as Andre Patrick protested, he could see men detained inside watching from the windows. Some were using their hands to make heart shapes; others held signs to the glass that simply read, “Help.”

Days earlier, a 59-year-old inmate there had died of complications from COVID-19. The jail is now reportedly the largest single known source of infections in the United States, with at least 251 detainees and 150 employees sickened by the coronavirus. More than 1,000 inmates have been released since early March, but criminal justice advocates worry it’s not enough. This week, Patrick joined dozens of other protesters outside the facility, leaning out of their parked cars to call for the release of more detained men and women to slow the spread of the virus.

But by the end of this week, that possibility looked far off. A federal judge on Thursday ruled against an emergency motion to release a large group of Cook County Jail inmates who are elderly or have preexisting conditions that would make them especially vulnerable to complications if they become infected. Many of the detainees are locked up pretrial because they could not afford bond.

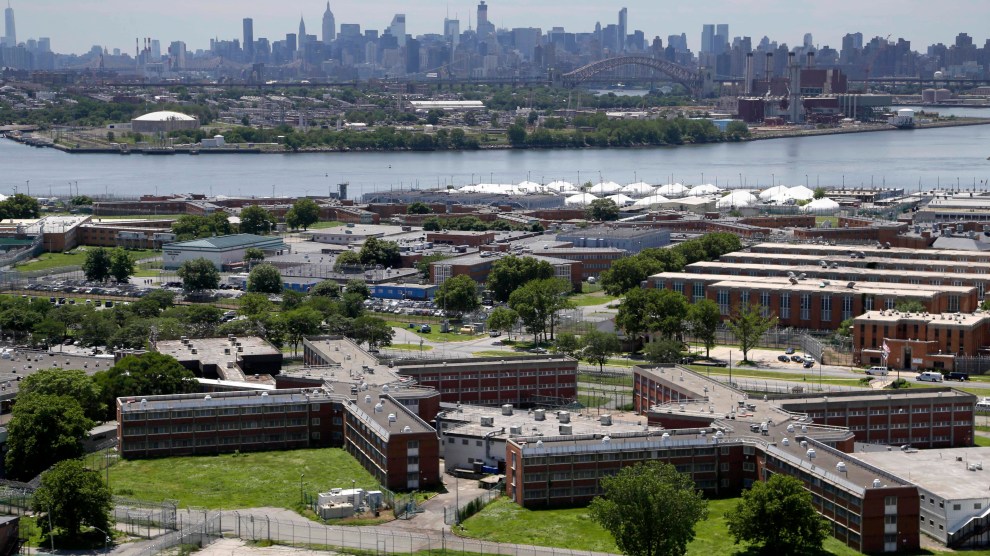

Public health experts say that because social distancing is nearly impossible in jails, the best way to slow the virus is to free inmates and make more space for those who remain; incarcerated people in several states are quickly filing suits in hopes of getting released and avoiding infection. But the lawsuits have had mixed results. A New York court released more than 100 people locked up for parole violations at Rikers Island jail complex, which has seen at least 288 infections, and a New Jersey court ordered the release of up to 1,000 jail inmates in March. Attorney General William Barr, meanwhile, has urged federal prisons to allow more inmates to be confined at home.

The Chicago plaintiffs filed their case on April 3. The class-action lawsuit includes Anthony Mays, a 38-year-old with diabetes who was referred for an evaluation for a heart condition when COVID-19 hit the jail. He’s housed in an open-dorm setting where dozens of beds are spaced about two feet apart, and multiple detainees on the tier have been removed after testing positive. Kenneth Foster, another plaintiff, also lives in a dorm setting and has stomach cancer, lung sarcoidosis, high blood pressure, asthma, and bronchitis. Other inmates named in the suit have Hodgkin lymphoma and blood clots; one man’s throat was reconstructed after he was shot.

“Inside accounts from Jail staff, detainees, and…medical personnel paint a picture of an unfolding disaster,” states the lawsuit, filed by civil rights attorneys who argue the county has violated people’s constitutional rights by failing to protect them from disease at the jail. The roughly 4,700 detained men and women at the Cook County Jail share phones, toilets, sinks, and showers, often with limited access to soap and hot water. Surfaces are infrequently washed, according to the suit, and people are quarantined in group settings, not individual cells, increasing the chance of infection. “It’s a lot of people, who were in a very intimate physical space with someone who is positive,” says Stephen Weil, one of the attorneys.

On Thursday, US District Judge Matthew Kennelly acknowledged the difficulties faced by Cook County Sheriff Thomas Dart in running the jail during a pandemic, but denied the lawsuit’s request for a mass release, saying that the plaintiffs should seek relief individually through state courts. In March, a state court held four days of emergency hearings to reevaluate bonds, sometimes lowering the amount of money that people were required to pay in order to leave the jail. During the week of the hearings, the jail’s population decreased by 424 detainees. Since March 9, Judge Kennelly noted, the jail’s population has decreased by 1,175 detainees—“bringing it to a record low, at least for the past few decades,” he wrote.

But attorneys for the detainees argue that individual bond hearings could take weeks or months, which is simply too slow given the rate of new infections. And some of the incarcerated people who went to the emergency hearings were denied release, including Jeffrey Pendleton, the 59-year-old who died last Sunday. One mother in the suburb of Arlington Heights told me her son sought relief at the emergency hearings and wasn’t even given the option of paying bond; now she worries about his safety. “Just because they are incarcerated doesn’t make them any less of a person,” she said, adding that her son has been jailed for two years pretrial.

The federal judge did issue a temporary restraining order requiring Sheriff Dart to provide soap to all detainees in sufficient quantities for frequent hand-washing; enough sanitation supplies to let staff clean surfaces regularly; and face masks to all detainees in quarantine. The order also requires the sheriff to stop holding new inmates in bullpens, which are enclosed, crowded cells, and to come up with a plan by Saturday for how to promptly test any detainee who experiences symptoms of the virus. The “conditions at the Jail have created a significant and unreasonable risk to the plaintiffs’ future health,” Kennelly wrote.

But in the order, Kennelly did not require the sheriff to change the dorm housing arrangements for inmates. He explained that while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called for six feet of distancing among the general public, the agency acknowledged that space limitations might make this distancing impossible in jails’ sleeping quarters. And CDC guidelines for jails do not require correctional facilities to individually isolate detainees who test positive for the coronavirus or have been in close contact with someone who has, since facilities may not have enough individual cells—details that the judge included in his ruling. “The issue there is whether the Constitution requires more than the Centers for Disease Control,” says Alexa Van Brunt, an attorney at the MacArthur Justice Center Clinic who is also representing the inmates.

In California, civil rights attorneys recently argued that the state violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment by failing to allow for six feet of distancing between inmates at state prisons, some of whom slept in dorms. But a panel of federal judges declined their request to move thousands of inmates out of the crowded prisons. The three judges said inmates had an Eighth Amendment right to be protected from disease, but added that dealing with a pandemic was beyond the court’s authority. (California has separately begun the process of releasing 3,500 inmates over the next two months.)

Sheriff Dart has defended his efforts to deal with the outbreak at the Chicago jail. “Unfortunately, all of this could have been accomplished without this unnecessary legal drama if the plaintiffs’ attorneys had accepted our invitation to work with us, rather than against us,” his office said in a statement to the Chicago Tribune after Thursday’s order. “Instead, this headline-seeking lawsuit is an unnecessary and costly distraction in the middle of such a crisis for our frontline officers and medical staff, whose round-the-clock work is saving lives.” Judge Kennelly acknowledged that the sheriff’s office said it was trying to distribute cleaning supplies more frequently and follow CDC guidelines, and to obtain enough masks and gloves for all employees at the jail.

That’s little comfort to Andre Patrick, the protester, whose friend is locked up in the jail, and whose cousin is incarcerated in a state prison. “In the society that we’re in, the people who are incarcerated aren’t looked at the same as someone in a nursing home,” he says. Days after the protest, he can’t shake the images of the men pleading for help in the windows, many of whom have yet to be convicted of a crime. “How are you going to have your day in court if you might not survive?” he says. “It’s really sad to see.”