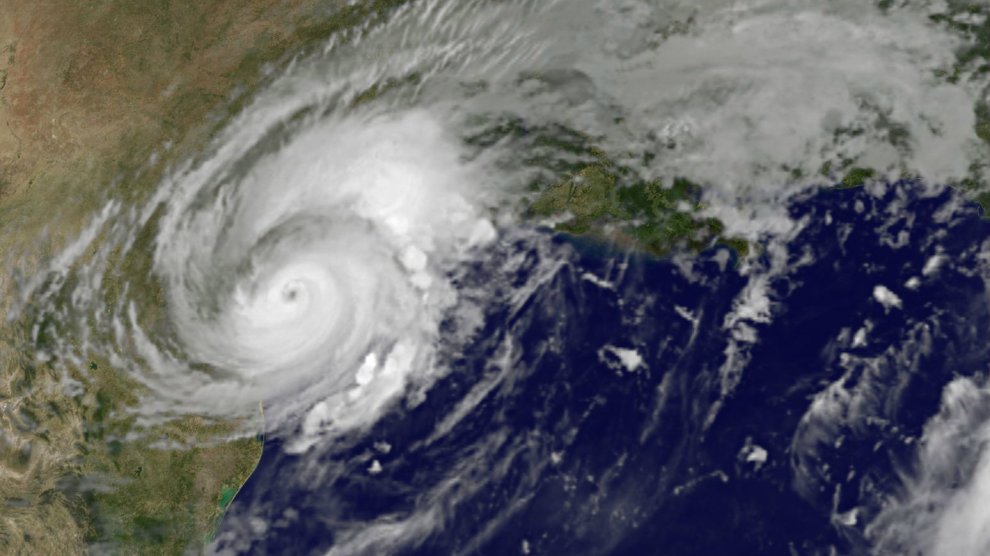

kozorog/Getty

This story was originally published by Newsweek and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In the coming weeks and even months, residents of Houston and other parts of southern Texas hit hard by Hurricane Harvey will be faced with the public health disasters that can result from dirty floodwater and landslides. The natural disaster has ostensibly turned the city into a sprawling, pathogen-infested swamp.

Up to 25 inches of rain have already accumulated in two days. Rains are expected to continue until Wednesday night, and by the end, Harvey will have dumped 40 to 50 inches on the metropolitan area. Heavy precipitation is turning entire neighborhoods into contaminated and potentially toxic rivers. For many of the city’s residents, contact with floodwater is unavoidable, putting them at risk for diarrhea-causing bacterial infections, Legionnaires’ disease and mosquito-borne viruses.

Chris Van Deusen, a spokesperson for the Texas Department of State Health Services, says officials are already making efforts to address the emerging public health nightmare. State and local officials recommend that people avoid drinking tap water, as health officials always do after a hurricane. But in the case of Harvey, abstaining from the public utility is likely to be crucial. Officials on Monday drained two reservoirs that are responsible for at least part of the city’s water supply in order to prevent subsequent infrastructure problems. Doing so likely brought drinking water into contact with dirty floodwater.

This leaves many, if not most, Houston residents without a potable water supply. All health officials are recommending that Houston residents boil water to kill off any bacteria, or use bottled water instead.

Stagnant water is a breeding ground for all sorts of microscopic pathogens. Pritish Tosh, an infectious diseases physician and researcher at the Mayo Clinic, says hurricane floodwaters may be contaminated with pathogenic Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria that can cause serious gastrointestinal illness. Other bacterium found in floodwaters include Shigella, which can also cause gastrointestinal illness in the form of diarrhea, vomiting, fever, stomach pain and dehydration.

Bacterial illnesses are a common and anticipated problem after epic hurricanes. A survey in the aftermath of Katrina identified cases of Vibrio illness caused by V. vulnificus, V. parahaemolyticus and other bacteria. Those bacterial illnesses led to a handful of fatalities.

Tosh also cautions the public about the risk of Legionnaires’ disease, which is caused by Legionella, bacteria found in in freshwater that easily spreads to human-made water systems during floods. Exposure to the bacteria occurs through inhalation of airborne moisture droplets. Legionnaires’ disease causes pneumonia-type symptoms as well as gastrointestinal illness and headaches.

Many bacterial illnesses resolve on their own, but some require antibiotics. Legionnaire’s disease, for example, requires a course of azithromycin or ciprofloxacin. Officials in Houston are stocking temporary medical mobile units with such antibiotics as well as tetanus vaccines to treat and prevent bacterial infections, says Van Deusen.

Floodwaters also impact indoor environments and make houses especially hospitable to mold. Multiplying mold spores carry serious public health risks, especially for people with existing mold allergies and asthma. For those individuals, mold exposure can trigger respiratory and breathing problems as well as rashes and general allergies. Flooding will only add to the city’s already swamplike summer climate, and mold is challenging to fight indoors without electricity.

“Houston is notorious for humidity,” says Jeff Dudan, a disaster recovery expert and founder and CEO of AdvantaClean, a nationwide franchisor specializing in emergency water removal and mold remediation.

Dudan, who has been involved in the cleanup of a number of large-scale hurricanes including Katrina and Sandy, has already dispatched some 200 employees from his North Carolina–based company to Houston to begin the long and arduous process of deep-cleaning and making indoor environments sullied by floodwaters habitable once again.

The state is also in the throes of mosquito season. Experts say that standing water is likely to cause an uptick in the city’s mosquito population, especially aedes aegyptiand aedes aegypti albopictus, which are vectors for a number of serious viruses including Zika and yellow fever. (In July, Texas reported its first locally transmitted case of the Zika virus of the season in southern Hidalgo County, which is about five hours south of Houston.) Extreme flooding makes mosquito control especially challenging; insecticides won’t be effective in large bodies of floodwater. Tosh says that for most people the only protection they have from mosquito bites is long-sleeve shirts and pants, and bug repellent containing DEET.

With more than 20 hospitals in the state already evacuated or temporarily closed, it may be difficult to treat the population for diseases caused by water-related pathogens. Van Deusen says the health department is prepared to investigate any illnesses that occur, especially in shelters and other close living quarters where thousands of Houston residents are staying temporarily as they wait out the storm