This story was originally published by High Country News and is shared here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

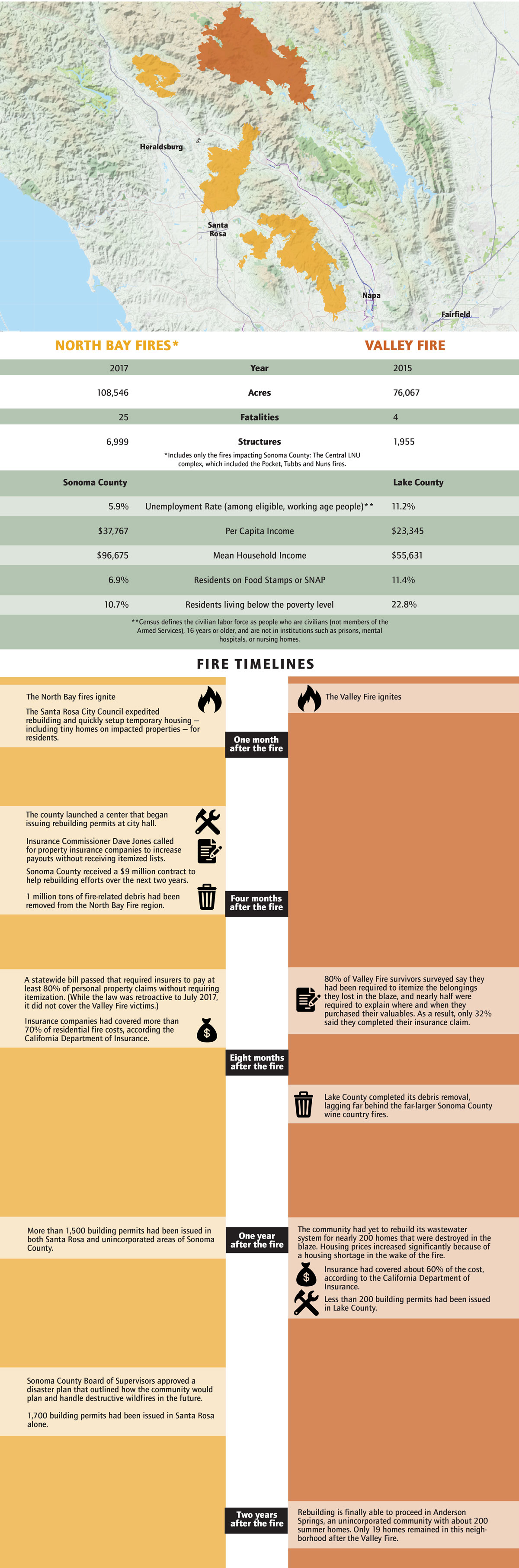

On the afternoon of September 12, 2015, the Valley Fire erupted near the outskirts of Cobb, California, an unincorporated community shadowed by Cobb Mountain in the Northern Interior of California. The fire grew so rapidly that it trapped the first responders from CalFire’s Helitack Crew 104. Four firefighters were badly injured and were rescued by CalFire Division Chief Jim Write, who drove through the smoke in his pick up and was able to transport the firefighters to a waiting helicopter. With its resources already depleted, fire crews were unable to stop the unencumbered Valley Fire as it charged toward populated communities. The blaze—sparked by a poorly installed hot tub wire—led to four deaths and destroyed 1,955 structures.

Two years later, a private electrical system ignited a cluster of fires—part of the North Bay complex fires. The flames spread through Lake County’s neighbor, Sonoma County, where more than 400 vineyards and the grapes of some of the world’s favorite wines sprawl across almost 60,000 acres. Survivors of the fast-moving fire were confronted by a towering wall of flames, and evacuation notices were received far too late. Twenty-five people died.

The 2015 Valley Fire and the 2017 North Bay fires occurred in adjacent counties, but the recovery of the communities has been disparate. According to a 2018 study published in PLOS One, the socioeconomics of a community and its ability—or inability—to recover following a disaster are linked.

Overwhelming insurance company requirements, gaps in financial support and lack of local political power make rebuilding a far more arduous process for poorer counties, such as Lake County, than wealthy ones like Sonoma County. As a result, recovery takes longer for less affluent communities.

Proper insurance coverage prior to the fire made a big difference in each of the counties. Surveys conducted by United Policyholders, a nonprofit research organization that advocates for the insurance policyholders, showed that approximately 14 percent of residents surveyed in Lake County were uninsured as opposed to less than 1 percent of those surveyed in Sonoma County. In Lake County, about 20 percent of residents surveyed by United Policyholders said their insurance companies had dropped them.

Not only were Lake County residents under-insured overall, they were also more likely to face burdensome requirements by their insurance companies after the fire swept through their community. A six-month post-wildfire analysis by United Policyholders revealed that survivors in Lake County were required to individually itemize their valuables in order to recoup lost costs. Survey respondents described the undertaking as “daunting” and a seemingly hopeless task.

For Sonoma County, however, Dave Jones, California’s Insurance Commissioner worked alongside policyholders to put tremendous pressure on insurance companies to waive consumers’ requirement to itemize lost belongings by publicly listing the companies that gave better (and worse) payouts without itemized lists. Many insurance companies responded to this pressure. State Senator Mike McGuire followed up on this by creating a bill that would wave inventory requirements during a governor-declared state of emergency, which was passed unanimously. Consequently, approximately 55percent of Sonoma wildfire survivors were required to list all their lost and damaged possessions as compared to nearly 80percent of Lake County survivors. “The less affluent the community, the less powerful the community, the less concessions the insurers make,” said Amy Bach, executive director of United Policyholders, “The insurers will just put up obstacles and you’ll see slower recovery.”