How should the Fed manage monetary policy? The hot topic these days is NGDP level targeting, an old idea that’s become newly popular as the economy continues to splutter and current Fed policy seems less and less effective. So let’s take a look at NGDP targeting and try to answer two questions:

- Question #1: Why target NGDP levels? Why not something else?

- Question #2: How do we target NGDP? Can the Fed really control it?

First, though, a technical definition. NGDP is nominal GDP. That is, it’s the total output of goods and services without any correction for inflation. So if the Fed’s target is, say, 5% growth per year, that could come from any combination of real GDP growth plus inflation. From a monetary perspective, you don’t care. If real GDP doesn’t grow at all, you want 5% inflation. If real GDP is on fire and growing 5%, you want no inflation. One way or another, though, you want spending — the number of dollars spent on goods and services — to grow on a stable, predictable path. With that, onward.

Warning! The following is both long and tentative, because I don’t really know what I’m talking about. So I’m putting the rest below the fold. If you click “More,” do it with the understanding that (a) some of it might be wrong and/or misguided due to a lack of understanding on my part of key concepts, and (b) you’re just following along for the ride as I try to puzzle through some stuff in public. OK?

Question #1: Why target NGDP levels?

The Fed has to target something — it can’t just conduct monetary policy randomly — and the usual target for central banks is inflation. The case for inflation targeting is pretty reasonable. In the long term, price stability is a good thing: inflation expectations have a big effect on the economy, so the credibility of a central bank’s promise to keep inflation under control is important. And in the short term, there’s a good case for focusing on inflation too: central banks manage growth mainly via control of interest rates, but during a deep recession, when interest rates are at zero, normal monetary policy loses traction. In a case like this, higher inflation is a boon. If interest rates are already at zero, but the Fed engineers inflation of, say, 5%, then money loses value every year that you hold it. Effectively speaking, the real interest rate is now -5%. This spurs consumers to spend and investors to invest, since if they don’t their wealth is simply going to get eaten away. In theory, then, focusing on low, stable inflation most of the time, but allowing higher inflation during a severe recession, is pretty good policy.

But NGDP supporters say there’s a problem with targeting inflation. It might work OK most of the time, but what happens if, for example, OPEC decides to embargo oil, the price of crude doubles, and the economy goes into the tank? Higher oil prices will feed into the broader economy, causing inflation, so the central bank will respond by tightening monetary policy. But with the economy in tatters, this is the exact wrong thing to do. David Beckworth provides a somewhat technical explanation of this dynamic here.

In practice, the Fed tries to control for supply shocks by focusing on measures like core inflation, which don’t include volatile food and oil prices, but even that’s not perfect. It might keep the Fed from tightening after an oil shock, but it probably won’t prompt them to loosen monetary policy, which is really what’s needed. Likewise — to pick an example out of a hat — even if you have a massive housing bust followed by a banking crisis, inflation might drop only a small amount. A Fed that’s obsessed with inflation would take that as a sign for only moderate easing, which is dead wrong. What’s needed is massive easing.

NGDP fans say that targeting NGDP levels, rather than inflation rates, solves this problem and fixes a whole host of others. In a nutshell, they suggest that NGDP targeting offers the following benefits:

- NGDP targeting is simpler. You don’t have to worry about core inflation vs. CPI vs. PCE or any of that stuff. You just add up all the spending on goods and services in current dollars — which is easy — and if it’s growing too slowly, you ease up. If it’s growing too fast, you tighten. (Scott Sumner, one of the leading supporters of NGDP targeting, goes further, arguing that price inflation measures in general have become fuzzy enough that they no longer provide a good guide for policy no matter which one you choose. The only reliable inflation rate is wage inflation, and NGDP is a pretty good proxy for wage levels.)

-

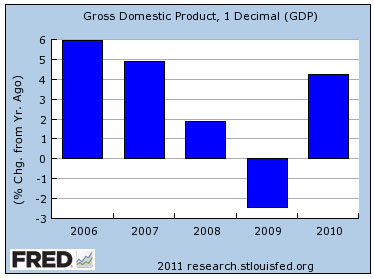

A focus on NGDP levels commits the Fed to playing catch-up. If your target is 5% NGDP growth and some kind of shock causes NGDP to rise only 2%, as it did in 2008 (see chart), the Fed would go into firefighting

mode, doing its best to force growth of 8% the next year. This kind of massive response is exactly what’s needed, and might have prevented the catastrophe of 2009, when NGDP fell 2%.

mode, doing its best to force growth of 8% the next year. This kind of massive response is exactly what’s needed, and might have prevented the catastrophe of 2009, when NGDP fell 2%. - NGDP is, basically, aggregate demand, and that’s the real thing we want to focus on. When AD falls, we want to stimulate the economy. When it grows too fast, we want to take away the punch bowl and slow things down. So if that’s what we really care about, why not focus on that rather than interest rates or inflation rates or something else? Essentially, what we’re doing is providing businesses with a guarantee that total spending in the economy will be predictable, and total spending is what they care about. If it’s $10 trillion this year, it will be $10.5 trillion next year and $11 trillion the year after that. And if something happens, and NGDP is only $10.2 trillion next year, we’re committed to playing catch-up and getting to $11 trillion anyway.

- NGDP targeting provides political camouflage for the fact that during a recession we’re willing to tolerate higher inflation. If we needed NGDP growth of 8% in 2009, that might well come from 2% real growth and 6% inflation. Higher inflation is actually what’s doing a lot of the heavy monetary lifting here, but calling it NGDP targeting makes it more politically palatable. What’s more, a firm NGDP target provides some credibility that inflation won’t spiral out of control. When the economy is growing normally again, NGDP targeting will automatically produce a more normal inflation rate, and when the economy is overheating, it automatically commits the Fed to cutting the inflation rate. So as long everyone believes the Fed is genuinely committed to NGDP targeting, inflation expectations will be kept anchored even when inflation rates go up.

So that’s it. That’s the case. Let’s say we find it persuasive. Hooray for NGDP targeting! (Even if it is just inflation targeting that’s been dolled up for public consumption and had some of the rough edges filed off.) Let’s move on.

Question #2: How do we target NGDP? Can the Fed really control it?

This is actually the tricky part. NGDP targeting might provide the Fed with different goals for monetary easing and tightening (i.e., when to do it, how much to do it, etc.), but it’s still fundamentally just a goal. Operationally, the Fed still has all the same tools at its disposal as it’s ever had, and there are basically two of them:

- Expectations setting.

- Open market operations.

This is where things start to get harder to grasp. Let’s take expectations setting first and use Nick Rowe as our foil. Here’s his proposed first step:

1. The Fed clearly announces its target path for NGDP. That’s by far the most important bit. Everything else is secondary. And if the Fed had credibility, that would be enough.

Hmmm. If I threaten to kill you with my bare hands I’ve clearly announced an intention. But you’d just laugh at me and go about your business. However, if Michael Corleone threatened to kill you, you’d be well advised to move some of your financial assets into the life insurance sector. So while a goal of some kind is obviously important, I’d say that credibility always comes first and foremost. The Fed can say “we won’t rest until we’ve met our NGDP target” or the Fed can say “we’re going to engage in massive monetary easing until the economy  picks up,” and really, the difference between the two is probably relatively modest. Credibility is the real key. Unless the market believes you can and will do what you say, neither goal is worth the foolscap it’s written on.

picks up,” and really, the difference between the two is probably relatively modest. Credibility is the real key. Unless the market believes you can and will do what you say, neither goal is worth the foolscap it’s written on.

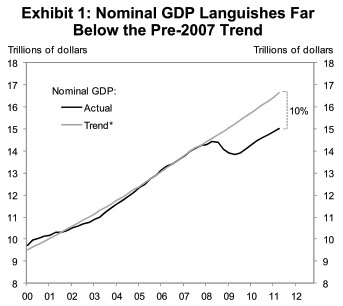

So let’s move on to that. Let’s say the Fed has clearly announced that it won’t rest until NGDP is back up to its trend level (see chart). What does the Fed have in its arsenal to make that happen? Answer: the same thing as always. It can buy up financial assets for cash, thus pumping money into the economy, and it can threaten to keep buying until it gets its way. Here is Rowe’s analogy to explain why this works:

There are two rooms at a party. The first room is nearly empty. The second room is nearly full. Because everyone wants to be where everyone else is. Then Chuck Norris enters the second room. He threatens to beat up 1 person at random in the first minute, 2 people in the second minute, 4 people in the third minute, and so on, until the room is empty. This is no longer an equilibrium.

A few people were nearly indifferent to being in the second room. So they leave even if the chance of them getting beaten up is tiny. That means there are fewer people left in the second room. This makes the second room slightly less attractive for those who want to be where everyone else is. And it slightly raises the probability of being beaten up by Chuck Norris. So more leave. [Etc.] Chuck Norris doesn’t have to beat up everyone in the room. He just has to threaten to beat up as many as it takes to clear the room. The number of people he will actually beat up is a lot less than the number he threatens to beat up. If his threat is credible, and everyone hears it, he doesn’t need to beat up anyone.

I get that this is just an analogy. Still, there are problems. Even Chuck Norris gets tired after a while. Is his threat to beat up everybody in the room really credible in the first place? And what if Jack Bauer is standing right near the door and gives Chuck one of those squinty-eyed looks? Beats me. Maybe it turns out that Chuck Norris is a badder dude than Jack Bauer — but then again, maybe not. Brad DeLong puts it this way:

The problem, I think, is that every time Nick Rowe writes “Chuck Norris won’t have to lift a finger” he is changing the situation from one in which Chuck Norris enters the room into one where a six-foot cutout of Chuck Norris is carried into the room, and an economist says: “this cardboard cutout will beat you up unless you move.” And people laugh.

And so we’re back to the question we’ve always had, regardless of whether we target NGDP or anything else: can the Fed credibly threaten to buy up enough assets to meet whatever goal it sets? Maybe. Brad DeLong again:

The government can buy more than Treasuries. After Treasuries, you buy GSE debt. And if that doesn’t work, you buy bank and corporate debt. And if that doesn’t work, you lend JPMorganChase $30 billion on the security of Jamie Dimon’s dog. And if that doesn’t work, you buy equities. And if that doesn’t work, you buy the services of construction workers–by which time you are explicitly doing money printing-financed fiscal policy.

The problem here is that contrary to Ron Paul’s fever dreams, the Fed doesn’t actually have the legal authority to literally buy anything it wants. In an emergency maybe it can get away with pushing the boundaries of what it’s allowed to do, but there are still limits. And Brad himself points to another problem:

The thing that scares me is that I am not at all sure what or how much the Fed would have to buy. If you had asked me back at the start of 2008 how much the Fed would have to buy in order to keep nominal GDP on its pre-2008 growth trend, I would have said that it was almost certain that the Fed could do it by expanding its balance sheet from $1 trillion to $1.5 trillion. And if you had asked me in the middle of 2008, I would have said that it was almost certain that the Fed could do it by expanding its balance sheet to $2 trillion. And if you has asked me at the end of 2009, I would have said that it was almost certain that the Fed could do it by expanding its balance sheet to $3 trillion. Yet here we are with a Fed with a $3 trillion balance sheet….

In its recent investors note, Goldman Sachs suggests that the Fed would need to buy about $2.5 trillion in assets to push NGDP back up to its trend level. However, Goldman Sachs also suggests  that this would lower long-term interest rates by 60 basis points — that is, by 0.6 percentage points.

that this would lower long-term interest rates by 60 basis points — that is, by 0.6 percentage points.

And this is where I start to boggle. Seriously? Our rock solid commitment to an NGDP target turns out to be based on achieving a reduction of 160 basis points in long-term rates (100 points from higher inflation and 60 points from lower nominal rates)? Since 2007, 10-year treasury rates have fallen 300 basis points (see chart). Does an additional 160bp really strike anyone as a Chuck Norris kind of threat?

I’ve got a hard time with that. If investors realize — and they will, since they’ve all read Goldman’s report too — that even a mega-QE program of $2.5 trillion is only forecast to reduce real long-term rates by 160bp, will they believe that’s enough? After all, for the past decade American investors have shown a very distinct unwillingness to invest in real-world American businesses regardless of interest rates. And if they don’t believe that 160bp is enough to spur investment and spending more than modestly, will they believe that the Fed is really willing to double down on its bet? And then double down again? Maybe they will, but I have my doubts.

So now we’re back to the age-old question of whether monetary policy can be effective all by itself in the face of a huge recession. I’m a million light years from being qualified to have a strong opinion about this, though obviously I’m a little skeptical that in any plausible real world it’s enough to get the job done. Atrios gets at this obliquely in this response to Brad DeLong:

If we’re going to actually move to more “unconventional” monetary policy, can we please recognize that the reason to do so is largely because conventional monetary policy — acting through the banking system — isn’t working?….If we’re going to give out dodgy loans, how about giving dodgy loans to people who might do something with the money other than visiting the Great Casino?

In other words, if we really want to be sure of boosting aggregate spending in the economy, why not have the government simply spend great gobs of money? Or, alternately, give great gobs of money to ordinary people, instead of working through the banking system?

To which I say: Yes. Let’s do both. Why take chances, after all?

Of course, neither of these things is going to happen. The federal government has no intention of spending great gobs of money because Congress is full of people who claim to be more afraid of deficits in the year 2020 than they are of a massive economic shortfall and sky-high unemployment in 2011. And the Fed is not going to endorse an unlimited program of asset purchases because — I think — it’s full of people who are (a) afraid of how they’re going to unwind all those asset purchases when the time comes to do it, and (b) whose fingers were badly burned in the 1970s and who remain panic stricken at the idea of deliberately allowing inflation to rise above 3%.

So that’s where we are. Details are important — NGDP or inflation? Tax cuts or federal work programs? — but we’re still, at core, talking about the same two things as always: the Fed taking a public position about monetary easing and then engaging in huge asset purchases to make its position stick, and Congress being willing to engage in massive deficit spending. Right now we’re not doing either, and we’re all paying a grim price for that.