One of the odder little subplots of the 2012 election has been the growth of poll denialism among Republicans. As Mitt Romney’s chances have grown ever dimmer, a cottage industry has sprung up on the right claiming that presidential polls suffer from liberal bias and Romney is really doing better than they say. “When the published poll shows Obama ahead by, say, 48-45,” explains conservative pundit Dick Morris, “he’s really probably losing by 52-48!”

Now, this is hardly in the same league as climate denialism or evolution denialism. What’s more, it’s perfectly understandable. It’s human nature to cast around for reasons to stay optimistic about a political contest that you feel deeply about. I remember a milder version of the same thing happening in 2004, as liberals dug deep into the October poll numbers trying to convince themselves that John Kerry had a better chance to beat George Bush than the topline numbers suggested. One poll had a small sample size. Another one had a bad likely voter screen. A third one suffered from a known house effect. Etc.

But it’s what happened next that’s instructive. A couple of years after the 2004 election, a guy named Nate Silver started deconstructing polls in minute detail and explaining exactly what made some polls good and others bad. His approach was unsparingly rigorous and his overarching message was: don’t kid yourself. The numbers are what the numbers are, and they don’t care if you’re a liberal or a conservative. Week after week, Silver dug deep into the minutiae of how polls are put together and how they’re conducted, writing  lengthy, table-laden posts that often meandered through several thousand words. Liberals loved it. Before long he was, for all practical purposes, the liberal patron saint of polling.

lengthy, table-laden posts that often meandered through several thousand words. Liberals loved it. Before long he was, for all practical purposes, the liberal patron saint of polling.

So far at least, the conservative approach has been….different. Their patron saint going into the last few weeks of the 2012 campaign is Dean Chambers, a blogger who runs a site called UnSkewed Polls. Chambers does not dig deep into the numbers. He doesn’t explain sample sizes and cell phone biases. He does just one thing: he reweights all the polls so they have the same proportion of Democrats and Republicans estimated by Rasmussen Reports, a pollster with a longstanding Republican house effect. Then he announces what the numbers are after his reweighting is done. Romney is a big winner every time.

Chambers doesn’t even pretend that his approach has any rigor. He adopted it, he told BuzzFeed, after seeing a poll that “just didn’t look right.” After a closer look, he decided that none of the others looked right either. And what does he think accounts for this widespread blundering among the nation’s pollsters? Not simple incompetence, Chambers says. It’s all quite deliberate. “Any poll that says NBC, CBS, or ABC is going to be skewed and invested in trying to get this President re-elected,” he explained.

This is, to put it bluntly, nuts. And it suggests a fundamental difference between left and right, one that Chris Mooney wrote about earlier this year in The Republican Brain. Neither side has a monopoly on sloppy number crunching or wishful thinking, but liberals, faced with a reality they didn’t like, ended up accepting reality and deciding to learn more about it. That’s the Nate Silver approach. Conservatives, faced with a reality they didn’t like, invented a conspiracy theory to explain it and then produced an alternate reality more to their liking. It’s a crude and transparently glib reality, but that’s apparently what the true believers want.

lengthy, table-laden posts that often meandered through several thousand words. Liberals loved it. Before long he was, for all practical purposes, the liberal patron saint of polling.

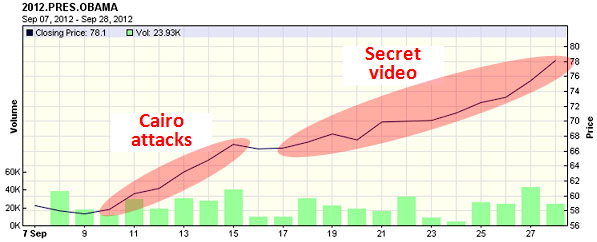

lengthy, table-laden posts that often meandered through several thousand words. Liberals loved it. Before long he was, for all practical purposes, the liberal patron saint of polling. meeting. These kinds of pieces are three-a-penny for decisions made in the White House or on Capitol Hill, but not so common for decisions made in the inner sanctums of the Eccles Building. But as you’ll recall, September’s meeting is the one where the Fed finally decided to implement QE3,

meeting. These kinds of pieces are three-a-penny for decisions made in the White House or on Capitol Hill, but not so common for decisions made in the inner sanctums of the Eccles Building. But as you’ll recall, September’s meeting is the one where the Fed finally decided to implement QE3,  is a terrific idea. But will this actually cause us all to buy more stuff?

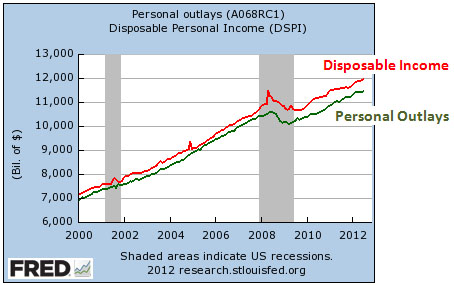

is a terrific idea. But will this actually cause us all to buy more stuff? Ryan Chittum points out a good example today of how misleading news reports can be when they fail to account for inflation. Here’s a sentence from a

Ryan Chittum points out a good example today of how misleading news reports can be when they fail to account for inflation. Here’s a sentence from a  many of the largest American market participants, including the big banks, have built high-speed trading desks and dark pools and as a result have a vested interest in protecting them against new regulations.

many of the largest American market participants, including the big banks, have built high-speed trading desks and dark pools and as a result have a vested interest in protecting them against new regulations.