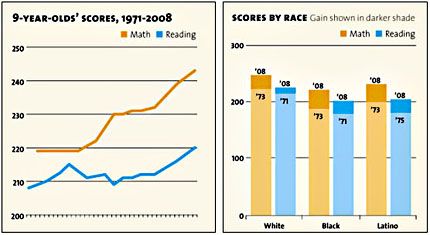

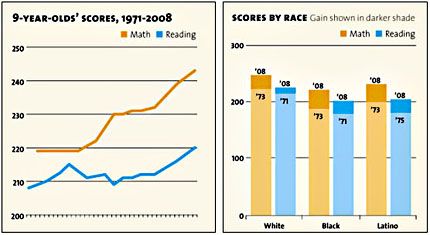

If you’ve read the several dozen posts I’ve written about NAEP test scores over the years, you already know about one thing that stands out: scores on math tests have improved a lot more than scores on reading tests. Despite (or because of?) the endless math wars of the past few decades, the evidence suggests that we’re doing  a better job of teaching math than we used to. Quite a bit better, in fact.1

a better job of teaching math than we used to. Quite a bit better, in fact.1

But why? Motoko Rich asks the experts and gets the following answers:

Teachers and administrators who work with children from low-income families say one reason teachers struggle to help these students improve reading comprehension is that deficits start at such a young age: in the 1980s, the psychologists Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley found that by the time they are 4 years old, children from poor families have heard 32 million fewer words than children with professional parents.

…Reading also requires background knowledge of cultural, historical and social references. Math is a more universal language of equations and rules. “Math is really culturally neutral in so many ways,” said Scott Shirey, executive director of KIPP Delta Public Schools in Arkansas.

….And while reading has been the subject of fierce pedagogical battles, “the ideological divisions are not as great on the math side as they are on the literacy side,” said Linda Chen, deputy chief academic officer in the Boston Public Schools.

I’d argue about that third bullet. The “ideological divisions” over math teaching have actually been pretty damn impressive for the past few decades, though it’s possible that they’ve calmed down lately.

The other two bullets sound more plausible, though. Low SES kids start out with a big reading deficit as early as kindergarten, and it’s hard to make up that deficit later on. The deficit in math is probably small or zero. I’m a little less sure about possible cultural issues, but that might be part of it too. And if I were speculating, I’d suggest that because language is more hardwired into the brain than math, it might just be a tougher nut to crack.

In any case, I just wanted to pass this along. There are a few topics that mainstream news organizations rarely mention—for example, the fact that test scores are up, not down, over the past few decades—and the math/reading dichotomy is one of them. It’s nice to see it at least get a mention.

1Up through 8th grade, anyway. Beyond that, test scores have been fairly flat in both reading and math.

John McCain went to Syria recently and, among other things, apparently ended up posing for a photograph with rebels who had kidnapped 11 Lebanese Shiite pilgrims. I think Joe Klein

John McCain went to Syria recently and, among other things, apparently ended up posing for a photograph with rebels who had kidnapped 11 Lebanese Shiite pilgrims. I think Joe Klein  a better job of teaching math than we used to. Quite a bit better, in fact.1

a better job of teaching math than we used to. Quite a bit better, in fact.1

“Those of us who report on state-level politics,”

“Those of us who report on state-level politics,”