Jim Manzi has a long blog post today about the Oregon Medicaid study that got so much attention when it was released a couple of weeks ago. Along the way, I think he mischaracterizes my conclusions, but I’m going to skip that for now. Maybe I’ll get to it later. Instead, I want to make a very focused point about this paragraph of his:

When interpreting the physical health results of the Oregon Experiment, we either apply a cut-off of 95% significance to identify those effects which will treat as relevant for decision-making, or we do not. If we do apply this cut-off…then we should agree with the authors’ conclusion that the experiment “showed that Medicaid coverage generated no significant improvements in measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years.” If, on the other hand, we wish to consider non-statistically-significant effects, then we ought to conclude that the net effects were unattractive, mostly because coverage induced smoking, which more than offset the risk-adjusted physical health benefits provided by the incremental utilization of health services.

I agree that we should either use the traditional 95 percent confidence or we shouldn’t, and if we do we should use it for all of the results of the Oregon study. The arguments for and against a firm 95 percent cutoff can get a little tricky, but in this case I’m willing to accept the 95 percent cutoff, and I’m willing to use it consistently.

But here’s what I very much disagree with. Many of the results of the Oregon study failed to meet the 95 percent standard, and I think it’s wrong to describe this as showing that “Medicaid coverage generated no significant improvements in measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years.”

To be clear: it’s fine for the authors of the study to describe it that way. They’re writing for fellow professionals in an academic journal. But when you’re writing for a lay audience, it’s seriously misleading. Most lay readers will interpret “significant” in its ordinary English sense, not as a term of art used by statisticians, and therefore conclude that the study positively demonstrated that there were no results large enough to care about.

But that’s not what the study showed. A better way of putting it is that the study “drew no conclusions about the impact of Medicaid on measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years.” That’s it. No conclusions. If you’re going to insist on adhering to the 95 percent standard—which is fine with me—then that’s how you need to describe results that don’t meet it.

Next up is a discussion of why the study showed no statistically significant results. For now, I’ll just refer you back to this post. The short answer is: it was never in the cards. This study was almost foreordained not to find statistically significant results from the day it was conceived.

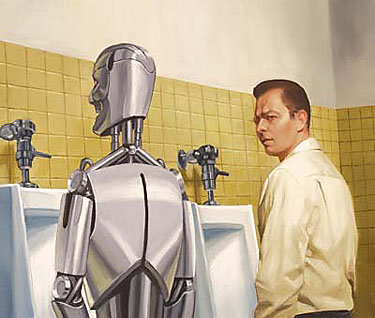

Whenever you talk about smart machines taking all our jobs, the usual pushback is that you’re being a Luddite—an argument that’s especially appropriate this year since it’s the 200th anniversary of the end of the Luddite movement. (Well, the 200th anniversary of the trial and conviction of the alleged ringleaders, anyway.) The basic argument is that all those skilled weavers in 1813 thought that power looms would put them out of jobs, but they were right only in the most limited way. In the long run, those power looms raised standards of living so much that everyone found jobs somewhere else (working in steel mills, building cars, operating power looms, etc.). So there was nothing to worry about after all.

Whenever you talk about smart machines taking all our jobs, the usual pushback is that you’re being a Luddite—an argument that’s especially appropriate this year since it’s the 200th anniversary of the end of the Luddite movement. (Well, the 200th anniversary of the trial and conviction of the alleged ringleaders, anyway.) The basic argument is that all those skilled weavers in 1813 thought that power looms would put them out of jobs, but they were right only in the most limited way. In the long run, those power looms raised standards of living so much that everyone found jobs somewhere else (working in steel mills, building cars, operating power looms, etc.). So there was nothing to worry about after all. of research, I decided on Lake Michigan as the key to my explanation of the chessboard analogy, but you’ll have to click the link to see what this means. It even comes with a nifty little graphic that our art department created to illustrate how Lake Michigan is just like a digital computer.

of research, I decided on Lake Michigan as the key to my explanation of the chessboard analogy, but you’ll have to click the link to see what this means. It even comes with a nifty little graphic that our art department created to illustrate how Lake Michigan is just like a digital computer. on Friday morning and that would be the end of it? Of course not. It’s explosive. So why were they seemingly so unprepared for any followup questions?

on Friday morning and that would be the end of it? Of course not. It’s explosive. So why were they seemingly so unprepared for any followup questions?