Karl Smith argues that the increasing stability of modern life might be making us more bubble prone:

Let’s imagine a simple model where we have two sources of risk. There is background you cannot avoid. And, there is personal risk that you create by through your own choices.

Policy makers have since Thomas Hobbes been attempting to drive down background risk. They have largely been successful. As a result our lives are getting more and more stable.

As that happens, however, folks are going to tend to take on more personal risk. There is a tradeoff between risk and reward tradeoff. As you face less background risk for which you not rewarded it makes sense to go for more personal risk for which you are rewarded.

….Said another way, attempts to prevent bubbles from forming will only make folks more complacent about bubbles. Eventually, a bubble will slip through the cracks. However, folks will deny it’s a bubble, because don’t you know, bubbles are a thing of the past. Even as it grows to massive proportions the smartest minds

will argue that it only looks like a bubble. If it were a real bubble, surely the Fed would have popped it by know.

Hmmm. That flew by a little fast. Are we really so sure that as society becomes less risky in general, individuals respond by taking more personal risks? It’s certainly possible, but what’s the evidence?

Let’s think about this by looking at a different example. Liberals like to argue that strong social welfare policies encourage risk taking. One reason not to quit your job and start up a cupcake chain, for example, is that you’ll lose your big-company health insurance, thus multiplying the financial risk you’re already taking by setting out on your own. Under this theory, universal healthcare makes entrepreneurship more likely since it removes one source of catastrophic risk from your decision.

Needless to say, I like this theory. Unfortunately, I’ve never been able to find any evidence that it’s true. And conservatives have an entirely different view: they believe that social welfare policies breed weakness and dependence. The more that you come to depend on government to take care of you, the less likely you are to feel motivated to do anything risky.

My own suspicion is that neither of these is quite true, but what is true is that as societies become richer, people are less motivated to take personal risks. You simply have too much to lose. I’d also argue that as societies become more educated, they tend to take fewer stupid risks.

But this is a two-edged sword. People in richer societies also have better safety nets when they fail, both personal (family, friends, etc.) and government-based (bankruptcy laws, safety net programs). And while we highly educated types might take fewer obviously stupid risks, perhaps we make up for this by taking more highly sophisticated risks that only seem less stupid on the surface.

So which is it? I don’t know, and I don’t think we can figure it out by arguing from first principles. Overall, though, my intuition tells me that my personal vulnerability to other people’s risky behavior is less today than it was a hundred years ago.

In any case, I’d like to see some evidence on this score. Do rich countries tend to breed more risk taking than poor countries? Has risk taking increased over the past few centuries? How do you even measure risk taking, anyway? A Wall Street trader risking a billion dollars is obviously taking a bigger absolute risk than an Indian peasant who takes out a $100 loan to buy a bicycle, but on a personal level they might actually be about the same. So what’s the right way to calculate this?

it sound like this was not a typical filibuster. He makes it sound like Democrats agreed to a special threshold in part to defeat that amendment they didn’t favor.

it sound like this was not a typical filibuster. He makes it sound like Democrats agreed to a special threshold in part to defeat that amendment they didn’t favor. the end, though, releasing the data didn’t make much difference because it turned out the professionals were interpreting it correctly.

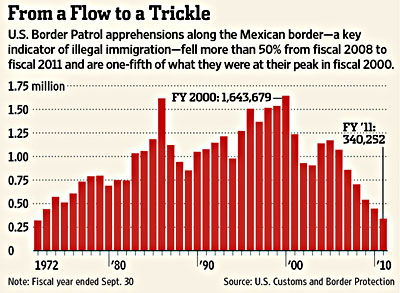

the end, though, releasing the data didn’t make much difference because it turned out the professionals were interpreting it correctly. new wave of Mexicans crossing the border illegally and yet another call for a path to citizenship for them. As far as conservatives are concerned, they were played for suckers in 1986, and they’re not going to fall for this con again.

new wave of Mexicans crossing the border illegally and yet another call for a path to citizenship for them. As far as conservatives are concerned, they were played for suckers in 1986, and they’re not going to fall for this con again.

The Pentagon is sending about 200 troops to Jordan, the vanguard of a potential U.S. military force of 20,000 or more that could be deployed if the Obama administration decides to intervene in Syria to secure chemical weapons arsenals or to prevent the 2-year-old civil war from spilling into neighboring nations.

The Pentagon is sending about 200 troops to Jordan, the vanguard of a potential U.S. military force of 20,000 or more that could be deployed if the Obama administration decides to intervene in Syria to secure chemical weapons arsenals or to prevent the 2-year-old civil war from spilling into neighboring nations.

are not a particularly important part of overall Apple profits, but Mac could and should be an important part of Apple strategy.

are not a particularly important part of overall Apple profits, but Mac could and should be an important part of Apple strategy.