On Thursday I wrote a post about this week’s filibuster of universal background check legislation. My topic was the unwillingness of news outlets to call it a filibuster even though 60 votes were required for passage. Why the reluctance? The reason is that, technically, it wasn’t a filibuster. Harry Reid negotiated a unanimous consent agreement with Mitch McConnell, and among other things they agreed that the background check amendment (along with all the other proposed amendments to the gun bill) would require 60 votes to pass.

Jonathan Bernstein objected. Here’s his nickel summary of what happened:

- There’s a filibuster.

- The two sides then decide how to settle the filibuster. The 60-vote threshold UC is an agreement on how to settle the filibuster. Not by waiting it out, not by a cloture vote, but by a 60-threshold vote.

- And then the vote itself both resolves the filibuster and resolves the issue. Under 60, the amendment is defeated by filibuster; over 60, it overcomes the filibuster, and also passes the amendment, all in one.

On Twitter, I joked that Bernstein and I disagreed only on petty details, not the actual question itself, since I think he’s right that this should be called a filibuster. But petty details are what the blogosphere was invented for, and they’re important here as a way of understanding why the press continues to refuse to call this week’s events a filibuster.

The key question is a semantic one. What’s the definition of a filibuster in the U.S. Senate? There are basically two approaches to this:

The strict rules-based approach. During the early 70s, in response to the increasing complexity of Senate life, a set of procedures emerged for conducting and resolving filibusters. Senators (usually from the minority party) were no longer required to actually speak to sustain a filibuster. Instead, they signaled their intent to filibuster by notifying their party leader to place a hold on a bill. Once this was done, the majority leadership would either negotiate a compromise or else schedule a cloture vote. If the cloture vote succeeded, the bill would proceed. If it failed, the bill died.

The broader academic approach. In the academic literature, the definition of a filibuster is broader. Here’s Gregory Koger: “Filibustering is delay, or the threat of delay, in a legislative chamber to prevent a final outcome for strategic gain. The key features are the purpose (delay) and the motive (gain) and NOT specifying the legislature or the method.”

Under the strict rules-based definition, what happened last week wasn’t a filibuster. There was no hold and there was no cloture vote. Under the broader definition, what happened was clearly a filibuster. The method wasn’t the classic one, but there was certainly a threat of delay in order to prevent a final outcome (passage of the background check amendment). The resolution was a unanimous consent agreement rather than a cloture vote, but that’s immaterial. It’s still a filibuster.

So here’s the question: why has the press been so reluctant to describe modern filibusters as filibusters? The actual conduct of filibusters has changed over the years, but for some reason style guides haven’t kept up. In fact, even 70s-style filibusters often aren’t described as filibusters. Reporters  seem to be stuck in an ancient era when a filibuster meant Jimmy Stewart performing a talkathon on the Senate floor, and they aren’t willing to call anything else a filibuster.

seem to be stuck in an ancient era when a filibuster meant Jimmy Stewart performing a talkathon on the Senate floor, and they aren’t willing to call anything else a filibuster.

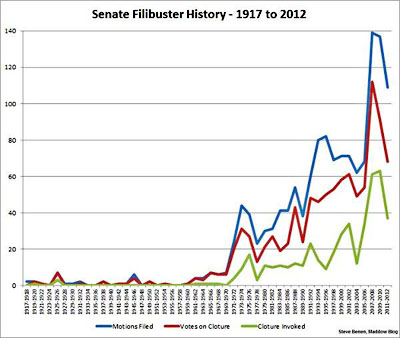

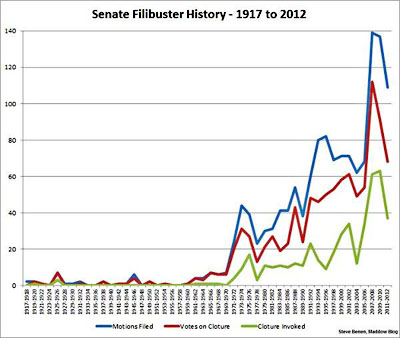

But Bernstein is right. Times change and procedures change. In the past, senators would talk and the opposition would either try to wear them down or negotiate a compromise. That evolved into a more modern form with holds and cloture votes. Then it evolved yet again into an institutionalized form where filibusters are simply assumed and the two party leaders negotiate a unanimous consent agreement based on that assumption. (This is one reason why cloture votes have decreased recently even as the Senate has filibustered more and more bills. Steve Benen’s chart on the right shows this.) Nonetheless, all of these things are filibusters. Only the methods differ.

So here’s a question for the public editors of the Washington Post and the New York Times: why do your style guides continue to insist that only a very specific set of old-style obstruction tactics can be called a “filibuster”? Why not keep up with the reality of legislating? In the modern Senate, unanimous consent agreements are now a common method of declaring and resolving filibusters. So why not call them that?

How long indeed? Let’s allow McManus himself to answer the question:

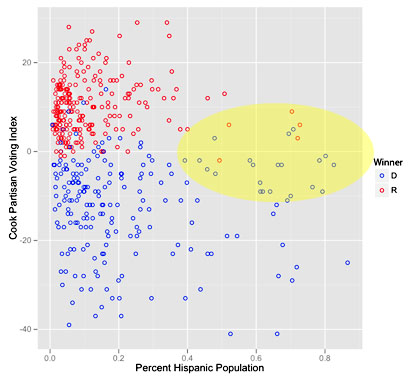

How long indeed? Let’s allow McManus himself to answer the question: shifts away from Democrats by Hispanics could be devastating. Under the 42 percent scenario….a 10 percentage point shift to the right would have handed Republicans 12 seats.

shifts away from Democrats by Hispanics could be devastating. Under the 42 percent scenario….a 10 percentage point shift to the right would have handed Republicans 12 seats. seem to be stuck in an ancient era when a filibuster meant Jimmy Stewart performing a talkathon on the Senate floor, and they aren’t willing to call anything else a filibuster.

seem to be stuck in an ancient era when a filibuster meant Jimmy Stewart performing a talkathon on the Senate floor, and they aren’t willing to call anything else a filibuster.

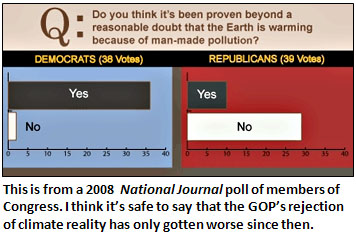

another indication of how ferocious the resistance on the right to immigration reform is going to get.

another indication of how ferocious the resistance on the right to immigration reform is going to get.