It would be quite an achievement to allow Iran, the world’s foremost state sponsor of terrorism, to play the role of injured party in this drama. But the Senate is poised to do just that.

Goldberg is talking about the possibility that the Senate will pass a sanctions bill against Iran just as the Iranians have finally agreed to come to the table and negotiate an agreement to dismantle their nuclear program. As Goldberg says, this makes sense only if you’re hellbent on a military strike against Iran and flatly eager to sabotage anything that might lead to a peaceful  settlement. It’s hard to believe that this is the position of the entire Republican Party as well as a pretty good chunk of the Democratic Party, but apparently it is. It’s especially hard to believe given the realities of what it would accomplish:

settlement. It’s hard to believe that this is the position of the entire Republican Party as well as a pretty good chunk of the Democratic Party, but apparently it is. It’s especially hard to believe given the realities of what it would accomplish:

While it could set back (though not destroy) Iran’s nuclear program, it could also lead to the complete collapse of whatever sanctions remained in place. In addition, it could unify the Iranian people behind their country’s unelected leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei — a particularly perverse outcome. And in some ways, an attack would justify Iran’s paranoia and pursuit of nuclear weapons: After all, the regime could somewhat plausibly argue, post-attack, that it needs to defend itself against further aggression. A military campaign should be considered only when everything else has failed, and Iran is at the very cusp of gaining a deliverable nuclear weapon.

….So why support negotiations? First: They just might work. I haven’t met many experts who put the chance of success at zero. Second: If the U.S. decides one day that it must destroy Iran’s nuclear facilities, it must do so with broad international support. The only way to build that support is to absolutely exhaust all other options. Which means pursuing, in a time-limited, sober-minded, but earnest and assiduous way, a peaceful settlement.

This is exactly right. As it happens, I doubt that we’ll be able to reach a final deal with the Iranians. In the end, I think Iran’s hawks have too much influence and just won’t be willing to give up their nuclear ambitions. What we’ll do then is anyone’s guess. But as Goldberg says, even if you’re a hawk who favors a military strike, surely you’re also in favor of demonstrating to the world that we did everything humanly possible to avoid it. What possible reason could you have for feeling differently?

what if it doesn’t? As it turns out, nothing much will happen.

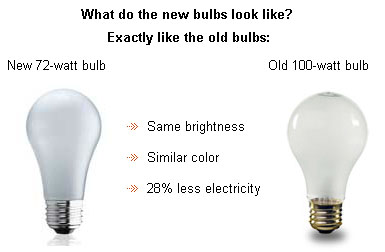

what if it doesn’t? As it turns out, nothing much will happen.  bulbs are still available right alongside the newer bulbs. All told, the transition is pretty much complete, so at this point there isn’t much to enforce anyway.

bulbs are still available right alongside the newer bulbs. All told, the transition is pretty much complete, so at this point there isn’t much to enforce anyway.

has plummeted since the housing bubble burst. This could be addressed with policy changes at the FHFA, which might be a better alternative than higher inflation anyway. I have two observations about all this:

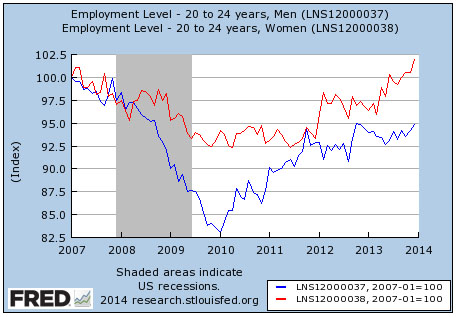

has plummeted since the housing bubble burst. This could be addressed with policy changes at the FHFA, which might be a better alternative than higher inflation anyway. I have two observations about all this: far worse than women. Male employment is still about 5 percent under its 2007 peak,

far worse than women. Male employment is still about 5 percent under its 2007 peak,