Yesterday I wrote briefly about Marco Rubio’s poverty reform proposal, and I was….unenthusiastic. I don’t believe that Rubio is really serious; I don’t believe Republicans will follow his lead even if he is; and I imagine that once Rubio provides us with details, his proposal will turn out to be little more than a plan to cut spending on the poor.

Jared Bernstein followed up last night with a bit more on those pesky details. For example, Rubio proposes that we should get rid of most federal anti-poverty programs and simply give the money to the states, where they can experiment with different approaches. But there’s a problem with block grants like this:

“Revenue neutrality” may sound technical and inoffensive, if not fiscally sound, but what it really means is the safety net will be unable to expand in recessions. Let’s see the details, but typically under these arrangements, states will be unable to tap the Feds for unemployment benefits, nutritional assistance, and all the other functions that must expand to meet need when the market fails. This would be a huge

step backwards, essentially enshrining poverty-inducing austerity in place of literally decades of policy advancements to meet demand contractions with temporary spending expansions.

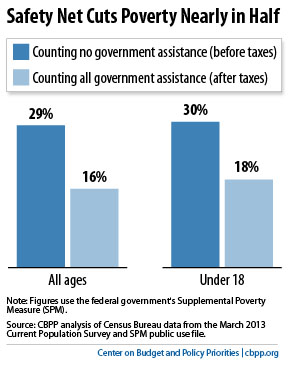

The chart on the right shows what Bernstein is talking about. The blue line shows TANF, the basic welfare program that was block-granted as part of the mid-90s welfare reform. During the Great Recession, spending on TANF didn’t budge. Conversely, both SNAP (food stamps) and unemployment insurance rose during the recession, as they should have. Will Rubio’s plan include automatic stabilizers based on eligibility requirements? Or will it strangle safety net programs by not allowing them to grow when the economy is bad? We’ll have to wait and see.

Rubio also wants to replace the EITC with wage subsidies. I’ve pointed out before that the experience of other countries that have tried this is decidedly inconclusive, so it’s something to be cautious about. Still, if it’s done right it has the potential to be an effective program. However, Bernstein is worried about Rubio’s apparent proposal to change the program to be more generous to married couples:

What Sen. Rubio appears to be up to here is targeting the so-called marriage penalty—the idea that since EITC eligibility is based on family income, combining incomes through marriage can lead formerly eligible workers to lose eligibility.

But it sounds to me like he’s losing the income targeting of the program and will end up shifting current EITC spending away from single parents with kids to married couples with kids (along with childless adults, who get little—too little—from the EITC). Given that kids in single parent families are already more likely to be poor than those in married families, the only way this idea could not increase child poverty would be if he spent considerably more on it than is being expended on the EITC. And that’s not likely what he’s got in mind.

This would fit with Rubio’s belief that government programs should encourage marriage, a popular notion in conservative circles. Now, it so happens that I think we should encourage marriage. In fact, I wish this were a more popular notion among the educated liberal class, which pretty clearly thinks marriage is a great thing but is often skittish about “imposing” its values on others. I say: be less skittish! Nobody wants to lock others into bad or abusive marriages, but generally speaking, marriage has a ton of benefits: for the couple itself, for their children, and for society. I’m all for it.

That said, I’m pretty skeptical that the government should be in the business of encouraging or discouraging marriage, and I’m even more skeptical that offering a few more or a few less dollars in welfare programs is likely to have any effect anyway. So I share Bernstein’s concerns. However, there’s no special reason to think the status quo is ideal in this regard, so if Rubio’s proposal ends up shifting spending a bit, I’m happy to evaluate it on the merits.

Still, the devil is really in the details here. EITC is a program with a lot of history behind it, and we know that it works pretty well. Wage subsidies show some promise, but they’re untested and extremely sensitive to program design. We’ll know how serious Rubio is about this stuff based on how much thought he ends up putting into his final proposal. I’ll be waiting.

failure (“Raising the minimum wage may poll well, but having a job that pays $10 an hour is not the American Dream”),

failure (“Raising the minimum wage may poll well, but having a job that pays $10 an hour is not the American Dream”),  all about getting out.” Andrew Sullivan points me to Rod Dreher, whose pithy reaction

all about getting out.” Andrew Sullivan points me to Rod Dreher, whose pithy reaction

deep and (b) last a really long time. So it’s no surprise that the Great Recession has produced such a long stretch of sluggish growth. Historically speaking, though, Neil Irwin reports that Reinhart and Rogoff think the United States

deep and (b) last a really long time. So it’s no surprise that the Great Recession has produced such a long stretch of sluggish growth. Historically speaking, though, Neil Irwin reports that Reinhart and Rogoff think the United States