What do you do when you have so much money you don’t know what to do with it anymore? Well, you can buy a bigger yacht, or gold-plated bathroom fixtures, or throw lots of fabulous parties. Or you can take up an expensive hobby. Collecting  old masters, say, or sponsoring NASCAR drivers.

old masters, say, or sponsoring NASCAR drivers.

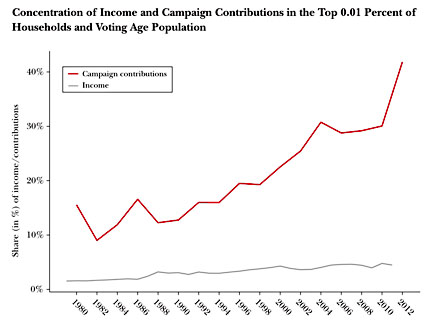

Or politics. Seth Masket points today to a fascinating study from a team of researchers who have been investigating political polarization and political contributions. As you can see in the chart on the right, the superrich used to account for about 10 percent of all political contributions. Then, starting around 1990, that started to rise steadily, reaching 30 percent by 2010. Then came Citizens United, and the sluice gates really opened. Within two years, the share of contributions from the superrich had skyrocketed to 40 percent.

But there’s an interesting wrinkle. Based on other data in the study, Masket concludes that the superrich are less polarized than the electorate as a whole:

The 30 wealthiest donors in the country are actually pretty moderate, at least judging from this measure. Apart from some extremists like George Soros and the Koch brothers, most exist between the party medians.

This presents an interesting conundrum. We know Congress has grown more polarized over the past three decades. And we know that the very wealthy are donating more and more each year. But the very wealthy aren’t necessarily that polarized. If they were buying the government they wanted, they’d be getting a more moderate one than we currently have.

This deserves more study. I’m not so sure that wealthy donors are quite as moderate as Masket thinks, since they often have strong views on one or two hobbyhorses that might get drowned out in broad measures of ideological extremism. The Waltons hate unions and Sheldon Adelson is passionate about Israel, but they might be fairly liberal about, say, gay marriage or Social Security reform. But does that make them moderate? If they spend all their money on the stuff they care about and none on the other issues, then no. They’re single-issue extremists.

This is pretty common among the anti-tax business crowd, for example. They might not care much about the hot buttons that animate the tea partiers, but they’re perfectly willing to support them as long as they oppose higher taxes on businesses and the rich. In practice, this makes them pretty extreme even if their overall political views are fairly centrist. If you’re willing to get in bed with extremists, then you’re effectively an extremist regardless of whether you publicly share their views on everything.

In any case, this is hard to get a handle on and requires more detailed research than we have at hand. Still, Masket’s observation is an interesting one and deserves a closer look. Are America’s rich really getting their money’s worth? Or has politics simply become an expensive hobby that they’re not very good at?

Max Fisher notes this morning that although President Obama got a lot of flak for his restrained response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, his approach of giving Vladimir Putin enough rope to hang himself has turned out to be

Max Fisher notes this morning that although President Obama got a lot of flak for his restrained response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, his approach of giving Vladimir Putin enough rope to hang himself has turned out to be  But few voters follow politics so closely, and even those reading detailed coverage of the bill’s failure would quickly get lost in an arcane procedural dispute that putatively caused its demise.

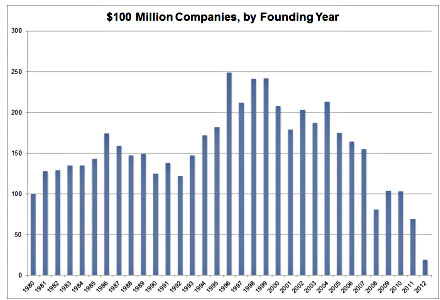

But few voters follow politics so closely, and even those reading detailed coverage of the bill’s failure would quickly get lost in an arcane procedural dispute that putatively caused its demise. thing, and the aging of the baby boomers should be thought of as a separate demographic issue, not a business startup issue.

thing, and the aging of the baby boomers should be thought of as a separate demographic issue, not a business startup issue. paying $37 for an unbundled cluster of sports channels, even if they would have paid the roughly $9 that it costs to get those channels as part of a bundled package.

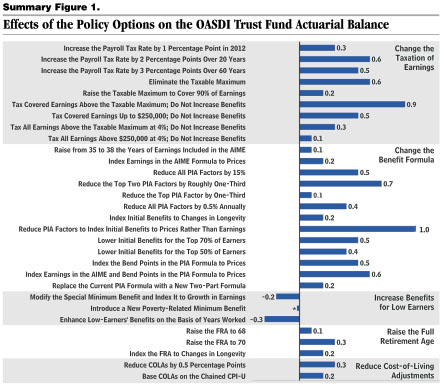

paying $37 for an unbundled cluster of sports channels, even if they would have paid the roughly $9 that it costs to get those channels as part of a bundled package. proposed changes to Social Security,

proposed changes to Social Security,