I’ve mentioned before that I have a few misgivings about Thomas Piketty’s thesis in Capital in the 21st Century. One of my misgivings is pretty basic: Piketty argues that r (the return on capital) is historically greater than g (the economic growth rate). Since the rich own  most of the capital, this means that the rich accumulate wealth faster than everyone else, which in turn means that rising income inequality is inevitable. But as capital accumulates, surely the return on capital should decline? After all, that’s what happens in every other market when there’s a glut of supply.

most of the capital, this means that the rich accumulate wealth faster than everyone else, which in turn means that rising income inequality is inevitable. But as capital accumulates, surely the return on capital should decline? After all, that’s what happens in every other market when there’s a glut of supply.

Piketty briefly addresses this objection, and concludes that although r will indeed decrease as capital accumulates, it won’t decrease much. But is that true? Larry Summers doesn’t think so:

[Piketty’s] rather fatalistic and certainly dismal view of capitalism can be challenged on two levels. It presumes, first, that the return to capital diminishes slowly, if at all, as wealth is accumulated and, second, that the returns to wealth are all reinvested. Whatever may have been the case historically, neither of these premises is likely correct as a guide to thinking about the American economy today.

Economists universally believe in the law of diminishing returns. As capital accumulates, the incremental return on an additional unit of capital declines. The crucial question goes to what is technically referred to as the elasticity of substitution….Piketty argues that the economic literature supports his assumption that returns diminish slowly (in technical parlance, that the elasticity of substitution is greater than 1), and so capital’s share rises with capital accumulation. But I think he misreads the literature by conflating gross and net returns to capital. It is plausible that as the capital stock grows, the increment of output produced declines slowly, but there can be no question that depreciation increases proportionally. And it is the return net of depreciation that is relevant for capital accumulation. I know of no study suggesting that measuring output in net terms, the elasticity of substitution is greater than 1, and I know of quite a few suggesting the contrary.

There are other objections to Piketty’s thesis, but it seems to me that this is one of the key criticisms—perhaps the key criticism. If r > g isn’t inevitably true, or even if it’s only slightly true (that is, r is only slightly greater than g), then everything falls apart. I suspect that this is going to be one of the main technical battlegrounds in the macro literature as Piketty’s theory gets hashed out over the next few years.

worked at the Office of Legal Counsel) justifying drone strikes against Anwar al-Awlaki.

worked at the Office of Legal Counsel) justifying drone strikes against Anwar al-Awlaki.  it’s not as if content companies just randomly dump lots of bits on the internet. They do it only when an end user requests those bits by calling up a website or streaming a movie or downloading a file.

it’s not as if content companies just randomly dump lots of bits on the internet. They do it only when an end user requests those bits by calling up a website or streaming a movie or downloading a file. which joined other top ABC News affiliate investigative teams around the country in a national hidden camera investigation into tire safety.

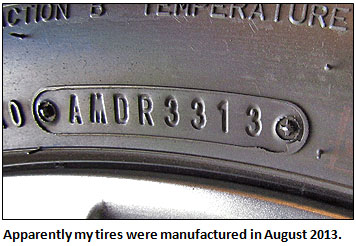

which joined other top ABC News affiliate investigative teams around the country in a national hidden camera investigation into tire safety.

Hey, looky here!

Hey, looky here!