Did you know that companies facing no competition are likely to charge you more? It’s true! But in case you’d like a bit of evidence for this truism, Binyamin Appelbaum directs our attention to a clever study of mortgage rates from the Chicago Fed. It turns out that when the federal government authorized the mortgage refinancing program called HARP, they set up  the rules in a way that discouraged anyone from participating aside from the original lender. This meant that, effectively, the original lender had little or no competition for the refinanced loan.

the rules in a way that discouraged anyone from participating aside from the original lender. This meant that, effectively, the original lender had little or no competition for the refinanced loan.

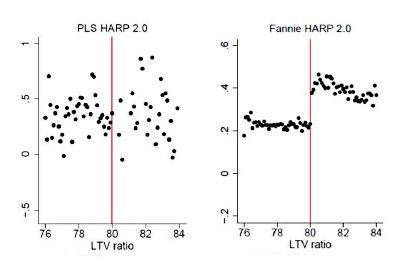

The results are shown on the right. The HARP rules took effect for mortgages with a loan-to-value ratio of 80 percent or higher. Private label mortgages, which didn’t fall under the new rules, show a normal range of interest rate spreads at all LTV values. But loans backed by Fannie Mae, which did fall under the new rules, show a sharp discontinuity upward precisely at an LTV of 80.

In other words, at exactly the point where lenders faced no effective competition thanks to HARP rules—i.e., Fannie-backed loans with an LTV of 80 or above—interest rate spreads suddenly increased by about 0.2 percent. Without competition, lenders were free to charge a little more, and they did.

I know: you’re shocked. And in case you’re tempted to think that 0.2 percent doesn’t really seem like that much, the authors point out that it adds up fast: “While the anti-competitive features of HARP may appear to have curtailed borrower gains by relatively small amounts, they resulted in sizable increases in profitability for a subset of lenders. These results further highlight the importance of restoring full competitiveness to mortgage refinancing markets.”

Quite so. Competition is good. We’ve paid less and less attention to this over the past few decades, and we do so at our peril. It’s the heart and soul of capitalism.