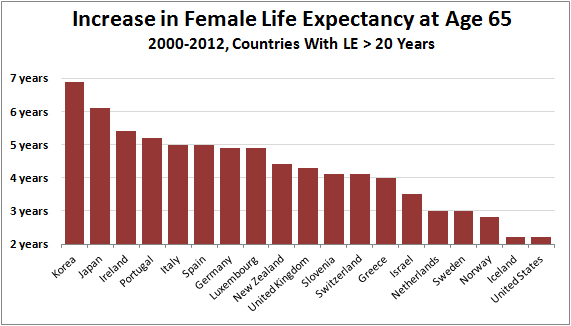

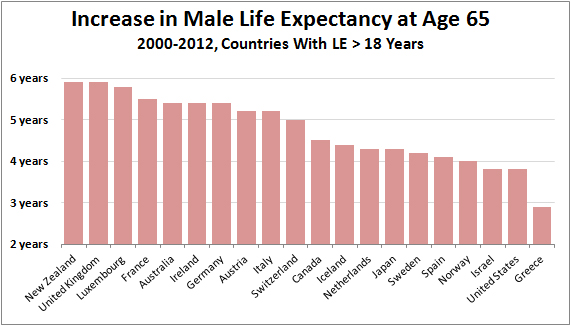

Among advanced countries with high life expectancies already, how is the US doing at increasing the life expectancy of men and women once they reach age 65? Not so good! Raw data below.

Among advanced countries with high life expectancies already, how is the US doing at increasing the life expectancy of men and women once they reach age 65? Not so good! Raw data below.

Ted Cruz has fired his communications director, Rick Tyler, for spreading a lie about Marco Rubio. Jeff Stein suggests this means there might be hope for us after all:

For months, the top Republican candidates have been engaged in a brutal knockout battle of negativity. Personal insults, lies about each other’s records, schoolyard taunts — nothing has been deemed out of bounds. The good news is that, so far as we can tell, this attack really has backfired….It may be comforting to know that even in this Lord of the Flies–style campaign cycle, some of the basic conventions just might retain a bit of power.

Anything is possible, but I’ll stick with the cynicism my hard-earned age allows me on this score. Still, there really are a couple of odd things about this episode:

It sure seems like there’s something goofy going on here. I’m just not sure what.

Do you ever wonder what Joe and Mika and Donald Trump talk about during commercial breaks on Morning Joe? Me neither. But we’re finding out anyway. Here’s a snippet of hot mic action from their prime-time town hall with Trump last week:

Trump: I watched your show this morning. You had me almost as a legendary figure. I like that.

[More good-natured chatting and joshing until the 30-second on-air warning.]

Mika: Do you want me to do the one on deportation?

Joe: We really have to go to some questions.

Trump: That’s right. Nothing too hard, Mika.

The audio comes from Harry Shearer, who jokes, “You can cut the adversarial tension there with a knife—a butter knife.” Unfortunately, the joke is on all of us.

From George Will, bemoaning the fate of a Republican Party in thrall to Donald Trump:

It is time to talk about his tax records.

OK, let’s talk! Unfortunately, this is not the first line of Will’s column, it’s the last. Is it a two-part column, and this is just the cliffhanger? I don’t know. I was reading the column for a different reason, when it suddenly stopped dead on this sentence.

So why was I reading the column? Because I was intrigued by the headline: “Donald Trump relishes wrecking the GOP.” You see, a few days ago President Obama claimed that Trump merely “says in more interesting ways” what every other Republican says too. Will isn’t buying:

Certainly not last week when Trump said, “I like the [Obamacare] mandate.”…Trump was not saying “what the other candidates are saying” when last week he said: “Every single other [Republican] candidate is going to cut the

hell out of your Social Security.”… Embraces torture and promises to kill terrorists’ families.

Trump quickly backed away from his mandate mistake, and other Republican candidates endorse torture as well—as have large majorities of Republican voters since long before Trump burst on the scene. They just don’t say so in quite such interesting ways as Trump.

So, once again, we’re left with Trump’s heresy on Social Security. That’s about it. With fairly trivial exceptions, Trump is quite mainstream on all the other big conservative hot buttons: taxes, health care, abortion, guns, military spending, regulations, climate change, crime, deficits, and smashing ISIS to bits. Given all this, he sure is getting a lot of mileage out of his slight nonconformities on issues like eminent domain and Planned Parenthood funding.

So is Trump really wrecking the GOP? I don’t see it. The GOP wrecked the GOP. They’re the ones who have spent the last 30 years building the kind of party that Trump appeals to. If Michael Moore entered the Democratic race, do you think he’d have the same effect? After all, he’s loud, he’s funny, and he’s unapologetically liberal.

But he wouldn’t have any serious impact. He’d build a small movement and get some good press, and that would be that. There just aren’t enough Democrats around who’d find his brand of rabble-rousing convincing presidential material. The Democratic establishment hasn’t spent the last 30 years building that kind of party.

So let’s knock off the crocodile tears about Trump wrecking the Republican Party. This is the party the Republican establishment built. They found it convenient, and they were pretty sure they could keep it under control. But they couldn’t. They started a bonfire to keep the rubes good and fired up, and now they’re getting upset because someone else is throwing in a few logs and taking ownership of it. Boo hoo.

Jordan Weissmann points out that we now have a health care plan from Donald Trump. For starters, Trump has now made clear that he doesn’t like the individual mandate after all—he just misspoke when he said that to Anderson Cooper a few days ago. What’s left are the three mighty pillars of Trump’s plan. First, he’s going to take care of the poor “through maybe concepts of Medicare.” Second, the Trump campaign has previously indicated that it will “provide individual tax relief for health insurance.” Third, after the scourge of Obamacare has finally been eradicated, the rest of us get this:

I will replace it with private plans, health savings accounts, & allow purchasing across state lines. Maximum choice & freedom for consumer.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 19, 2016

Amazingly, this is going to produce health care nirvana. “The plans will be much less expensive than Obamacare…you’ll get your doctor, you get everything you want to get, it’ll be unbelievable.”

As Weissmann points out, this is just your bog-standard Republican health care plan with an extra dash of Trumpian crowing. It won’t just work better than Obamacare, it will be unbelievable. In fact, “you get everything you want to get.” How much more can you ask for?

To the extent that it makes any sense to discuss Trump’s policy proposals, there are a couple of takeaways from this:

So that’s that. As usual, Trump is just a standard-issue Republican once the dust has settled, and he has no more idea about how to fix health care than any of the rest of them. He’s just more willing than most to brag about how great his plan will be.

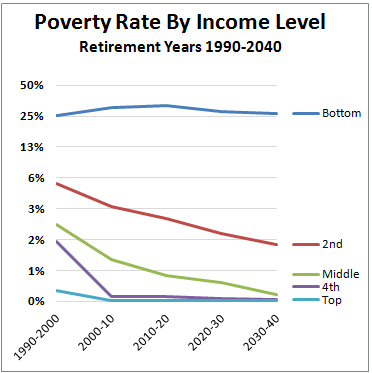

The current rate of poverty among the elderly is 9.8 percent, compared to 15.7 percent for those under age 65. But what about the future? The Social Security Administration projects that poverty rates will continue to decline for the elderly. About 7 percent of depression babies, who started retiring in 1990, currently live in poverty, compared to a forecast of 5.7 percent for Gen Xers, who  will begin retiring in 2030. However, these averages hide some stark differences:

will begin retiring in 2030. However, these averages hide some stark differences:

Not all groups are expected to do so well. Among high school dropouts, poverty rates are projected to increase from 13.5 percent to 24.9 percent…before declining to 18 percent for [GenXers]….Given the projected increase in minorities and immigrants, as well as the historic increase in women’s labor force participation, retirees with low labor force attachment are increasingly low-educated, low-skilled, and disabled. Not surprisingly, those retirees are projected to have very high poverty rates.

By 2030, SSA forecasts that poverty will be all but eradicated for every income group except one: the very poorest. This is unsurprising but nonetheless far-reaching in its policy implications: If you are poor during your working career you will continue to be poor when you retire. If not, then not. Our retirement programs should be set accordingly.

In case you’ve ever wondered about the value of a narrow 5-point win in a state you were expected to take easily, just take a look at today’s headlines. The margin of victory doesn’t matter. The headlines in all four of our biggest daily newspapers were clear as a bell: Hillary won and her momentum is back. That’s the story everyone is seeing over their bacon and eggs this morning.

Jeff Stein makes a potentially important point today:

On Saturday, about 80,000 voters participated in Nevada’s caucus — roughly two-thirds of the total that came out in 2008….Low turnout in Nevada wasn’t an outlier. New Hampshire saw 10 percent fewer voters in 2016 than it did eight years ago. In Iowa, turnout was also down — from 287,000 in 2008 to 171,000 this year.

….Sanders thinks “the core failure” of Obama’s presidency is its failure to convert voter enthusiasm in 2008 into a durable, mobilized organizing force beyond the election. Sanders vows to rectify this mistake by maintaining the energy from the campaign for subsequent fights against the corporate interests and in congressional and state elections.

The relatively low voter turnout in the Democratic primary so far makes this more sweeping plan seem laughably implausible. Three states have voted, we’ve had countless debates and town halls, and there’s been wall-to-wall media coverage for weeks….And yet … we have little evidence that Sanders has actually

activated a new force in electoral politics. If he can’t match the excitement generated by Obama on the campaign trail, how can he promise to exceed it once in office?

Of course, it’s one thing to say that Sanders hasn’t generated huge turnouts in a primary against a fellow Democrat, but that doesn’t mean he couldn’t generate a huge turnout against a Trump or a Cruz. The problem, of course, is that Hillary Clinton would quite likely generate a huge turnout as well. The prospect of either Trump or Cruz in the Oval Office would do wonders for Democratic panic no matter who the nominee is.

Sadly, turnout is a red herring. The real lesson of this year’s election is that candidates have learned there are no limits to what they can promise. Campaigning is always an exercise in salesmanship, and salesmen always overpromise. This year, though, we have two candidates who cavalierly and repeatedly promise the moon without making even a pretense that they have the slightest notion of how to accomplish any of it. And voters love it! Trump’s crowds go wild over the idea of Mexico paying for a wall and Sanders’ audiences go equally wild over his plan to blow away the entire American health care system and replace it with the NHS. This is the year that fantasy sells, and it sells big.

The conventional wisdom is that this is happening because voters are uniquely angry this year and attracted to outsiders who say they’re going to blow up the system. Maybe so. But I’ve heard that story pretty much every year for nearly my entire adult life, and weak economy or not I don’t really buy it. What’s different this year isn’t the electorate, it’s the candidates. American voters have always had an odd habit of simply believing whatever presidential candidates say, regardless of plausibility or past record, and this year two candidates have tested this to destruction. And guess what? It turns out that a lot of Americans will almost literally believe anything. I mean, China bashing and Wall Street bashing have always been good for some cheap applause, but this year we’re hearing blithe claims about crushing China by taxing them to death and smashing big banks into little bitty pieces, and the crowds are applauding even harder.

Trump and Sanders have shown that you can take overpromising to a far higher level than anyone ever thought possible. Is this unique to 2016? Or will others learn this lesson too? I guess we’ll have to wait for 2020 to find out.

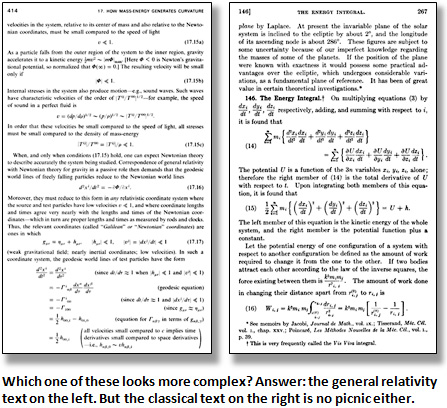

Yesterday I tackled a vexing problem: Is general relativity really that hard to understand? In one sense, of course it is. But when it receives the treatment that most scientific theories are given, I’d say no. For example, here’s how Newton’s theory of gravitation is usually described for laymen:

far apart, the attraction is one-ninth. Etc.

far apart, the attraction is one-ninth. Etc.Easy peasy! Objects are attracted to each other via certain mathematical rules. But hold on. This is only easy because we’ve left out all the hard stuff. Why are massive objects attracted to each other? Newton himself didn’t even try to guess, famously declaring “I frame no hypotheses.” Action-at-a-distance remained a deep and profound mystery for centuries.1 And another thing: why does the gravitational attraction decrease by exactly the square of the distance? That’s suspiciously neat. Why not by the power of 2.1 or the cube root of e? And nothing matters except mass and distance? Why is that? This kind of stuff is almost never mentioned in popular descriptions, and it’s the reason Newton’s theory is so easy to picture: It’s because we don’t usually give you anything to picture in the first place. Apples fall to the earth and planets orbit the sun. End of story.

Well then, let’s describe Einstein’s theory of gravity—general relativity—the same way:

Not so hard! Once again, there’s nothing to picture even though this is a perfectly adequate lay description of general relativity. The trouble starts when we do what we didn’t do for Newton: ask why all this stuff happens. But guess what? In any field of study, things get more complicated and harder to analogize as you dive more deeply. For some reason, though, we insist  on doing this for relativity even though we happily ignore it in descriptions of Newton’s theory of gravity. And this is when we start getting accelerating elevators in space and curved spacetime and light cones and time dilation. Then we complain that we don’t understand it.

on doing this for relativity even though we happily ignore it in descriptions of Newton’s theory of gravity. And this is when we start getting accelerating elevators in space and curved spacetime and light cones and time dilation. Then we complain that we don’t understand it.

(By the way: if you study classical Newtonian gravity, it turns out to be really complicated too! Gravitation, the famous Misner/Thorne/Wheeler doorstop on general relativity, is 1200 difficult pages. But guess what? Moulton’s Introduction to Celestial Mechanics pushes 500 pages—and it only covers a fraction of classical gravitation. This stuff is hard!)

Relativity and quantum mechanics are both famously hard to grasp once you go beyond what they say and demand to know what they mean. In truth, they don’t “mean” anything. They do gangbusters at describing what happens when certain actions are taken, and we can thank them for transistors, GPS satellites, atom bombs, PET scans, hard drives, solar cells, and plenty of other things. The mathematics is difficult, but often it looks kinda sorta like the math for easier concepts. So quantum mechanics has waves and probability amplitudes because some of the math looks pretty similar to the math we use to describe ocean swells and flipping coins. Likewise, general relativity has curved spacetime because Einstein’s math looks a lot like the math we use to describe ordinary curved objects.

But is it really probability? Is it really a four-dimensional curve? Those are good ways to interpret the math. But you know what? No matter how much you dive in, you’ll never know for sure if these interpretations of the math into human-readable form are really correct. You can be confident the math is correct,2 but the interpretations will always be a bit iffy. And sadly, they won’t really help you understand the actual operation of these theories anyway. Objects with mass attract each other, and if you know the math you can figure out exactly how much they attract each other. Calling the path of the objects a geodesic on a 4-dimensional curved spacetime manifold doesn’t really make things any clearer. In all likelihood, a picture of a bowling ball on a trampoline doesn’t either.

But we keep trying. We just can’t help thinking that everything has to be understandable to the h. sapiens brain. This makes interpreting difficult math an excellent way to pass the time for a certain kind of person. It’s a lot like trying to interpret the actions of the Kardashian family. Lots of fun, but ultimately sort of futile if you’re just an ordinary schmoe.

1General relativity and quantum mechanics finally put everyone’s minds at ease by showing that the action wasn’t actually at a distance after all. Unfortunately, they explained one mystery only at the cost of hatching a whole bunch of others.

2We hope so, anyway. But then, Newton’s math looked pretty damn good for a couple of centuries before it turned out to be slightly wrong. That may yet happen to general relativity and quantum mechanics too.

UPDATE: I’ve modified the third bullet of the relativity list to make it more accurate.

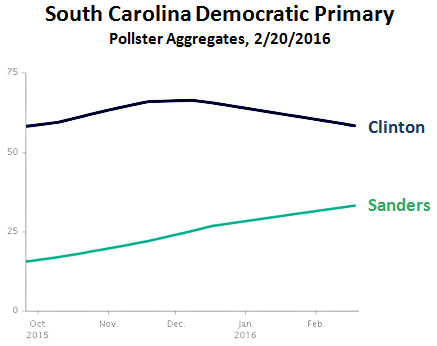

Well, it looks like Hillary Clinton won Nevada after all. Only by about five points, probably, but that’s enough. It means she avoids a crippling week of headlines declaring her a loser and anointing Bernie Sanders with all the momentum.

Well, it looks like Hillary Clinton won Nevada after all. Only by about five points, probably, but that’s enough. It means she avoids a crippling week of headlines declaring her a loser and anointing Bernie Sanders with all the momentum.

That’s why even a few points can make all the difference. Clinton is 25 points ahead in South Carolina, and now she’ll probably be able to keep most of that lead, which will produce yet more good press heading into Super Tuesday. If she runs the table there or even comes close—which she has a good chance of doing—it’s pretty much over for Sanders.