What in God’s name is this all about? In its motion filed Friday to force Apple to create a special version of iOS that would allow the FBI to crack the San Bernardino attacker’s iPhone, a footnote revealed that Apple and the  FBI had discussed several options for obtaining information on the phone:

FBI had discussed several options for obtaining information on the phone:

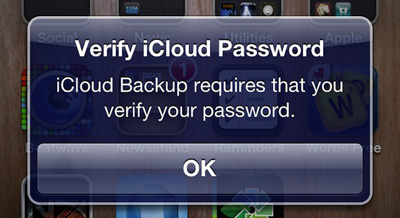

The four suggestions that Apple and the FBI discussed (and their deficiencies) were….(3) to attempt an auto-backup of the SUBJECT DEVICE with the related iCloud account (which would not work in this case because neither the owner nor the government knew the password to the iCloud account, and the owner, in an attempt to gain access to some information in the hours after the attack, was able to reset the password remotely, but that had the effect of eliminating the possibility of an auto-backup).

With the iCloud password changed, the iPhone can’t connect to the iCloud account and do a backup. But Apple says it wasn’t Syed Farook who changed the password:

Apple executives said the company had been in regular discussions with the government since early January, and that it proposed four different ways to recover the information the government is interested in without building a backdoor. One of those methods would have involved connecting the iPhone to a known Wi-Fi network and triggering an iCloud backup that might provide the FBI with information stored to the device between the October 19th and the date of the incident.

Apple sent trusted engineers to try that method, the executives said, but they were unable to do it. It was then that they discovered that the Apple ID password associated with the iPhone had been changed. (The FBI claimed earlier Friday that this was done by someone at the San Bernardino Health Department.)

Friday night, however, things took a further turn when the San Bernardino County’s official Twitter account stated, “The County was working cooperatively with the FBI when it reset the iCloud password at the FBI’s request.”

This is pretty bizarre. Why did the FBI say it was Farook in their court filing if they knew it wasn’t? And how did the San Berdoo Health Department change the iCloud password, anyway? You need the old password to do that. But if they know the old password, why can’t they change it back? Very mysterious.

UPDATE: Apparently there are a couple of ways this could have happened. If the Health Department knew Farook’s email account, they might have been able to use the “Forgot my password” option to reset it. Alternately, if the phone was MDM managed, they might have been able to reset the passcode remotely. However, that seems unlikely since they would have had other, better options if they had been using MDM.

Why did the Health Department have the phone, anyway? I’m surprised the police or the FBI didn’t snatch it instantly.

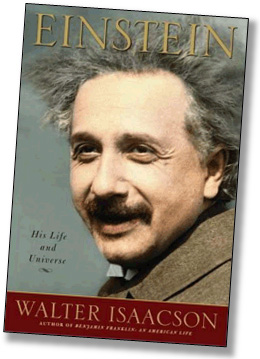

Bob Somerby is reading Walter Isaacson’s biography of Albert Einstein, which he calls “a pleasure to read.” Except for one thing: Isaacson’s description of the theory of relativity is incomprehensible.

Bob Somerby is reading Walter Isaacson’s biography of Albert Einstein, which he calls “a pleasure to read.” Except for one thing: Isaacson’s description of the theory of relativity is incomprehensible.

act in question” unless they choose to amend it.

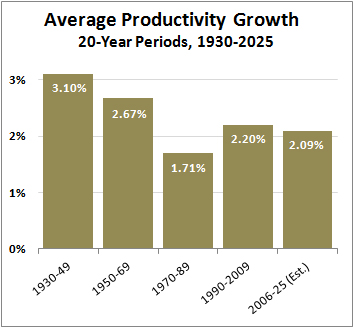

act in question” unless they choose to amend it. you frequently see productivity fall and then make up ground when you look at more than just a few years at a time. For the final bucket, I averaged actual numbers from 2006-15 with Friedman’s estimate for 2016-25. You can see the result on the right.

you frequently see productivity fall and then make up ground when you look at more than just a few years at a time. For the final bucket, I averaged actual numbers from 2006-15 with Friedman’s estimate for 2016-25. You can see the result on the right. I’m about to do that too. But here’s roughly what I think she should say:

I’m about to do that too. But here’s roughly what I think she should say:

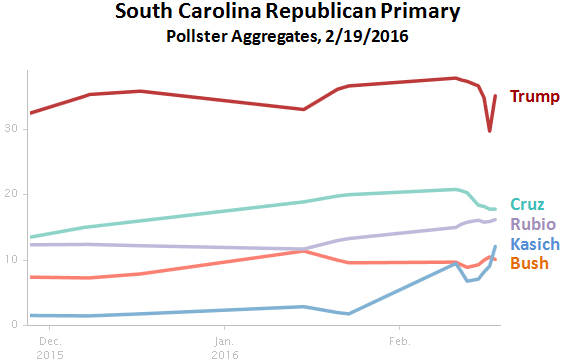

Exciting news! Former South Carolina governor Mark “Appalachian Trail” Sanford has endorsed….

Exciting news! Former South Carolina governor Mark “Appalachian Trail” Sanford has endorsed…. immigration reform. So like any president, he triaged. He spent his time on other things in hopes that he could make a successful run at immigration reform a little later. Was this the right call? We’ll never know, but it sure strikes me as correct.

immigration reform. So like any president, he triaged. He spent his time on other things in hopes that he could make a successful run at immigration reform a little later. Was this the right call? We’ll never know, but it sure strikes me as correct.