Art Spiegelman started drawing comics professionally in the 1960s, but he achieved perhaps his greatest fame with the two volumes of “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale.” Drawing Jews as mice and Nazis as cats, Spiegelman recounted his parents’ experiences during and after the Holocaust. “Maus” won him a Pulitzer Prize — the first for a graphic novel — in 1992. Over the next decade, Spiegelman took a hiatus from comics, creating much of the cover art for The New Yorker and publishing a series of children’s books with his wife.

But after witnessing, up close, the events of September 11, 2001 — he lived, literally, in the shadow of the World Trade Center — Spiegelman returned to comics. He crafted a series of ten broadsheet-sized pages about the attacks and their aftermath, titled “In the Shadow of No Towers.” Originally published in several European newspapers, the series has now been collected in a book of the same name, combining Spiegelman’s ten pages with reproductions of selected turn-of-the-century comics that influenced him.

“Before 9/11 my traumas were all more or less self-inflicted,” he writes in the book’s introduction, “but outrunning the toxic cloud that had moments before been the north tower of the World Trade Center left me reeling on that faultline where World History and Personal collide — the intersection my parents, Auschwitz survivors, had warned me about when they taught me to always keep my bags packed.”

Spiegelman, in San Francisco recently on a book tour, talked with MotherJones.com about Sept. 11, his book, his politics, and life in the shadow of no towers.

MotherJones.com: Could you describe your experience on Sept. 11?

Art Spiegelman: My wife Françoise and I were heading out of our lower Manhattan loft, which was about ten or so blocks from the towers, to vote that morning. We heard a roar overhead, saw a plane go into the tower. At first, I thought this was a small plane, just looking at it. It was so out of the parameters of what one’s used to seeing. Our daughter had just started going to school at Stuyvesant, which is a block or so from the towers, and was in fact used as a triage center after the towers fell. Years before, Nadja had been in preschool down in Tribeca when the car blew up in the tower, so we were primed to know, “Oh, disaster, we have to get her.” So while other people were beginning to come charging their way out of that part of lower Manhattan, we were weaving our way in to get to Stuyvesant, not knowing the scope or extent of anything — although the second plane hit before we really galvanized and ran down there. We got into that school through the power of Françoise’s hysteria and tears; we were able to get past the security guard who was trying to keep all the parents outside. Once inside, it took them over an hour to locate our daughter among the 3,000 students at the school, in the course of which the first tower fell and the building shook. They were able to locate Nadja finally. A few minutes after we left the building, the second tower fell. It looked very specific — the 110-story glowing bones of the tower kind of evanesced into the surrounding air and glowed, and the bones became the toxic cloud that we and a lot of others outran and what most people saw of the fallen towers.

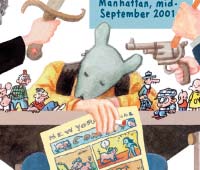

MJ.com: In the first panel of the book, you describe the feeling of waiting for the other shoe to drop. At what point do you think people moved past that feeling?

|

AS: It changed with every block away from Ground Zero. By the time you were uptown, people seemed normal to me — until I got out of New York about a month or so later and realized, “Everybody in New York is still thoroughly freaked out.” But even though it’s somewhat sublimated at this point, it’s a wound that’s pretty close to the surface. Even when you get to small towns in Iowa, there’s still this feeling of “our mall could be hit.” Some of that fear is worked with and played with, but it’s still there to be prodded. It’s not a historical event; it’s very much a present moment even for those who aren’t living within a mile or half-a-mile radius of it. For me, certainly, I have a daily rhythm that doesn’t include panicking about the other shoe dropping in the way that I did a good four or five months after the attack.

My panic about other shoes dropping is [now] more focused on whether the Bush/Cheney gang gets to live out another term or not, not whether Al Qaida will hit us or not. I have not totally succeeded in domesticating my paranoia, although right now it probably is more focused on the Bush/Cheney gang than on the Al Qaida sleeper cells, which may be wrong-headed. They’re equal threats in some ways; it’s not to downplay the latter. But the Al Qaida and fundamentalist Muslim threat seems to work on a very long time clock. They don’t seem to be deeply moved by American events. So at the moment, I’m more focused on the domestic threat.

MJ.com: In the book, you talk about how Sept. 11 made you feel more a part of New York, as a rooted New Yorker for the first time. Why is that?

AS: There’s a kind of — I don’t know if patriotism is the right word, but maybe it is — this feeling of identification with one’s geography, with home. My geography’s really the half-mile radius around my studio, and everything else gets more abstract, even Queens or the Bronx. And it certainly gets very abstract by the time I’m trying to encompass the whole country. But my neighborhood was so obviously vulnerable and wounded, it’s brought up a kind of genuine affection. I’m not the sort who’s likely to wear an “I love NY” t-shirt, but I genuinely felt a real surge of affection for my main street. Even though I can be angry at my mayor, angry when the Bloomberg police were put into action on the days of the convention protests, it’s an amazing city that I can say is my city.

MJ.com: How did the events of that day push you back into doing comics after a long break?

AS: This is a book that came about by accident, and not just the accident of living ten blocks from this particular event. The way I do comics, it sort of takes forever, and here I was at one of these moments where I didn’t think I was going to live until the next morning, when we were in the heart of the disaster. And it was with great regret, this feeling that “you really blew it. You spent years avoiding making comics whenever you could,” out of the kinds of laziness that came from feeling there were in some ways greater rewards for doing single images or writing essays than from the harder task of putting it all together in comics form. At that moment tough, I realized I really wanted to make comics again.

I couldn’t make them faster than I did, but I was trying to make them so that they could run once a month approximately, and they became a digested version of a diary, like the most important elements of what was seething in my head is what became the page. I really didn’t think we had much of a future, so I really was believing, “maybe I’ll stick around long enough to see if it’s printed okay, but I’m not sure.” And I certainly didn’t think of them in terms of posterity or making a book or anything. That came later in the cycle of making the pages, when I realized it was a pretty dumb format to have made if you want to do a book because they were giant-size pages, they didn’t reduce down well, they didn’t chop up into being other pages well, so finding a format for what’s ultimately a close-up fragment of a diary seemed like a difficult task. So now, although I’ve vowed to make comics full-time, here I am having spent most of last spring designing, writing and producing a book out of those pages that I made a year earlier, and now I’m on a book tour for a few months, so I’m still not doing comics. So so much for good intentions.

MJ.com: How has the reaction to the book in the U.S. compared with when the pages originally ran in Europe?

AS: In Europe, it seemed to be very highly praised, but I think I struck most Europeans as a kind of thinner and less-on-message version of Michael Moore, somebody who could reassure them that not every American was nuts. Because what was out-of-bounds here was well within the mainstream of French, German and British discourse. It was just taboo here to say certain things. There is more sophistication about what comics are in Europe, even though that’s changing in America. Here, it’s on the best-seller list, but the reviews have been pretty violent. I’ve never had such turbulent reviews.

MJ.com: Because of the subject matter?

AS: Yeah. We have a very close attachment to this stuff. Now, some of the reviews are clearly biased politically, they have to do with the fact that there’s a politics to this series of pages and the attitude that informs it is now seen as “humorous Bush-bashing.” But it wasn’t done to be funny, and it wasn’t part of a chorus when the pages were made. Just taboo statements. At this point, almost the only real truth-telling we’ve been getting on an ongoing basis has been through comedy, “The Daily Show” and so on. As a result, the book may have a different frame in people’s mind than it had when it was made, but that’s the nature of ephemera.

Some of the negative reviews are, I think, examples of the displacement that I was feeling during the time I was making these pages. There’s a section called “Weapons of Mass Displacement,” there’s one page where I was thinking about how the air in New York was thoroughly toxic. If it wasn’t for real-estate interests and the stock market having to get back up and running, they would have had to evacuate Manhattan if they were being conscientious about the needs of the people. Instead, the mayor comes along and bans smoking in bars. It was that kind of event everywhere. Like being attacked by Al Qaida and then bashing Saddam Hussein’s head. It was all displacement.

Similarly, I’m attacked on this book by one reviewer, in a very articulate review, for being narcissistic. But what’s actually more to the point is America is very narcissistic. Seeing the towers attack the way Americans see it is outscaled. This seems like a transgression that couldn’t be looked at with any perspective; it was an everything’s-changed moment. It is actually an everything’s-changed moment because of how big America is. I’m not in any way dismissive of what happened. Nevertheless, the degree of response is in some way a narcissistic response. So to have that word keep cropping up in the review, to me, just seemed like one more version of displacement. So the reviews have been hitting me from different corners and in different ways, and it kind of makes me proud. Because in the same week to be called a moron by Time and a genius by Newsweek made me feel like okay, the book is throbbing with something. It’s got some kind of life in it.

MJ.com: Do you have a sense of when this subject matter became less taboo in America?

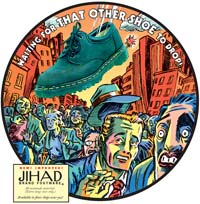

AS: To the moment, to the day. There was one image that was most upsetting to the editors who were seeing the pages while I was in the process of making them. That’s the one where I’m surrounded by Al Qaida and my own government and feel equally threatened by both as I’m trying to doze off and look at old Sunday comics on my drawing table. When it came out, that image was really shocking to the editors who were considering the pages. Yet in September of last year, the New York Times — which was one of the places clearly shocked by this — did an arts section, front-page interview with me, and the main image on the arts section was that panel, run quite large.

Already by last September, the press began feeling a little bit sheepish at having been as cowardly as it was, and even on occasion came up with some mea culpa apologies for how poorly it covered the run-up to the war. And yet, I still don’t think of us as having a really vigorous press. I think of us as now living through a ritual where, as one approaches an election, one is supposed to have lively debate of the “issues.” The issues being, “is somebody bald with a snarl better than somebody with a lot of Breck-like hair and a smile?” But nevertheless, the issues have to be covered before an election, so there’s room for a tussle of opinion, even some that seem as off the crank as those panels were.

MJ.com: You talk in the book about finding comfort in old comics from the turn of the last century. Why were those comforting to you?

AS: I think a lot of America turned to art and culture after Sept. 11. I know the sales of bibles went shooting up, but so did the sales of poetry. I think in a crisis one looks to one’s culture, partially to give validation to why one would want that culture to survive. It was our civilization being attacked, and finding what was beautiful in it was important to many Americans afterward, to almost validate America’s civilization. But I didn’t have the capacity to appreciate things that had been made, if this divide still holds, in a high-art vein. Poetry that was made to be read by people after one’s dead.

I think part of what drew me to these old Sunday comics, aside from just a natural affinity for them that’s been lifelong, is that they weren’t made to last. They were just made for one news cycle. They were made by people who were indeed inventing a medium, but who were mainly involved in punching a clock and trying to express as much of their personality as they could for that moment without the belief that anybody would ever look over their shoulder and see it again. That meant it was like eavesdropping on a whole other time, as if you could watch somebody dancing in the street in 1900 — not a movie of it, but to actually see somebody doing that. That was visible in these old comics. Some of them achieved great wit, great beauty, a kind of grace. But a grace that was meant for the trash can, which seemed like what everything around me was about, and this was accurately echoed by these old papers. In a way it’s like something as monumental as these towers was obviously ephemeral, as ideals and systems of government seemed ephemeral, not built to last based on the way things were unfolding and have been unfolding. These ephemeral objects took on a great emotional weight for me. They indicated what it was to be alive at a different moment where the world was ending, as always, on the front page. But in the inside pages where the comics were, there was grace. And I think that’s why I turned to them then, even though my conceit specifically in these pages is that newspaper comics were born right next to Ground Zero. So those old characters’ bones were disinterred when the bones of the towers fell, and I ended up having to channel them into the work I was making.

MJ.com: In addition to including those characters in your own pages, why did you decide to devote half the book to reproductions of those comics?

AS: When I began to finally think of this as some kind of book, the notion of what’s ephemeral and what will last became central to that project. So the book sort of divided itself into two towers — my ephemeral plates, and ephemeral plates from a hundred years earlier. To me, that’s what allows there to be a kind of happy ending, the fact that there’s a dialogue between past and present. That as time starts up again after this timeless moment of these glowing embers of a tower that still look like a tower right before it falls, the moment lasts forever. And it’s not a kind of affectionate, easy nostalgia. It’s the kind of nostalgia that has to do with the severe sense of loss that life is and that, ultimately, cities are. Cities are constantly losing chunks of themselves every day. [In California], you get to lose big chunks in earthquakes every hundred years. But every day, there’s stores going out of business, there’s people dying on the streets, there’s new buildings going up and buildings getting torn down. And ultimately, that present that you’re living in is built on and with a lot of the past.

MJ.com: Do you see your future comics discussing politics or current events?

AS: I’ll be able to answer that Nov. 3. It’s not like I really identify with Kerry’s positions strongly. They’re actually fairly self-contradictory. Short of calling him a flip-flopper, it does seem to me that once one realizes how egregiously badly we’ve behaved in Iraq, it’s very glib to say “we broke it, it’s ours to fix.” Because, whatever the Pottery Barn rule is, when it’s broken, it’s broken. And most of the time, broken things can’t be fixed once they’re shattered. So we can either get deeply engulfed in a war that has no possible happy ending based on serious analyses, or we can find ways to retreat and just offer some kind of buffer to what happens financially but not necessarily be involved in a war per se. It’s broken, and Kerry can’t say that based on the corners he’s backed himself into.

Still, I’m so grateful he has a chance to win because the alternative is to go to hell very quickly. By people who’d, in fact, like us to go to hell quickly so that they can get raptured up. I would rather go to hell more slowly, and I think that Kerry’s the go-to-hell-slowly party at this point. That’s the only one you can root for. If it goes slowly enough, I’d be glad to return to my life and business as usual, doing comics rather than more essays and more single images. But I don’t necessarily want to be caught in the sway of the totally ephemeral possibilities of political cartooning. One of the problems is that political cartoons have the shelf life of yogurt, at best. Even if you’re seconds ahead of your time, those seconds come a few seconds later, and then you’re reduced to just being a footnote in a history book by having a cute illustration to help illustrate for recalcitrant high school students what the Teapot Dome scandal actually was. As a result, it’s not exactly where I’d like to focus my immediate energies. But I can’t really answer that until I get the very visceral feeling of what things feel like at this end of this year. It’s a very cusp moment in general.