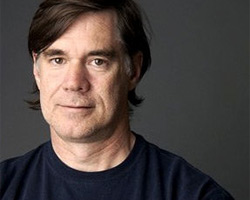

Film director Gus Van Sant has long shaped queer cinema, most notably with his 1985 feature Mala Noche. After a stint in Hollywood’s limelight (you may know him as the director of Good Will Hunting), Van Sant has returned in recent years to art-house cinema with the completion of his “Death Trilogy.” Recently, Van Sant spoke with Mother Jones about his previous life as a painter, his gay high school mentor, and the challenges of filming Milk.

Mother Jones: I didn’t realize how much anti-gay sentiment there was in San Francisco in the ’70s. This was an education for we San Franciscans who weren’t there.

Gus Van Sant: It was very highly charged. It was the birth of a whole class of people who just weren’t really above ground before 1969. My art teacher in junior high was a very out gay man and a mentor to me. He would tell us about Greenwich Village and show us the Village Voice and describe his life, but it was all sort of subversive and below the radar. He identified as gay but as far as the whole idea of being out and gay, except for people like him, it just wasn’t there. The ’50s and ’60s were sort of a transitional period. By the ’70s it was becoming more vocal and more legally accepted. It had a birthing phase, which it still has today. When you sit here and see the things that are in the film, it’s shocking, but there are still problems today.

MJ: What was your awareness of Harvey Milk when this all happened in San Francisco?

GVS: Very minimal. I lived in LA, and LA went through the same Prop 6 [the Briggs Initiative, a 1978 California ballot measure that would have banned gays and lesbians from working in public schools], but the personality of Harvey Milk I didn’t really know. I didn’t know that he was the first openly gay politician in the States when he was. I heard the story only when he was shot, basically on the news.

MJ: How long have you been trying to get this project done, from the idea in your head to now?

GVS: There was an incarnation in the early ’90s when I was going to film the movie in place of Oliver Stone filming it in ’93. So that was when I first really investigated Harvey and learned more about him. Then the script showed up last year, so between then and now, there were 12, 13 years.

MJ: I’m glad Oliver Stone didn’t do it.

GVS: You are?

MJ: I don’t think he could’ve done the same with the script. Was someone shopping it or was someone assigned to it?

GVS: There were producers and there was Warner Brothers and Robin Williams was going to be in it and it was pretty ready to go. There were screenplays that Oliver had written, there was one that was written under my directorship, that was sort of right after Oliver left as director, so it was pretty close to being ready.

MJ: I feel a lot of people are aware of parts of the story, but they don’t know the whole thing. It’s alluded to in the film that Dan White should have just come out of the closet already. It kind of explains how someone like him could kill because of projecting his own conflict. Is that true?

GVS: It’s complete speculation. I can’t really say myself, but my theory on Dan White’s sexuality is not as distinct as someone that was saying he was for sure a man who was trapped in the closet. I don’t know if I can support that, because there’s a lot that I don’t know. But it’s easy to think that. It’s intriguing. It’s possible.

MJ: You have so many different projects: You’re a novelist and you also work with short films. What keeps your creative juices going?

GVS: Free time keeps me going. It’s just something that’s always been a part of my life. I was originally a painter, and I made films sort of as an extension of that, and then I started to try to make dramatic films because the early films were experimental films. The novel [Pink] was really sort of sitting down and writing something.

MJ: It sounds like your career is actually you living in your playground.

GVS: Yeah, it’s its own playground.

MJ: What was shooting in San Francisco like?

GVS: I’ve always heard that San Francisco was a hard place to shoot in, but now I got to see why. For us it took a lot of time just to move around the city with the hills and the streets; if you have a relatively big production, there’s just no place to land. Which is weird because you’d think it would be harder in other cities. There were location problems, but they were worth it; we didn’t mind going through the trouble.

MJ: I was amazed at all the locations, like the crowd scene on Castro and Market Street.

GVS: I was afraid of that, because I always feel really guilty just stopping traffic and that kind of stuff, but it worked out.

MJ: Casting James Franco as Milk’s lover Scott Smith was such a great choice. How did that develop?

GVS: I had known him about 10 years ago when a friend of mine brought me to a play that he had written called The Ape.

MJ: And he’s in school for writing now.

GVS: Yeah, he’s writing and going to film school, and he’s made a couple of feature films. People like James are more like ideas that you’re referencing from other films, so I think we just made this decision like we should offer this to James. He came over and we talked about my other films more than Harvey Milk, and he was into it. Even though I knew James, I didn’t know about Freaks and Geeks, and I was mystified when he appeared in Knocked Up, and I was like, “That’s weird,” but I didn’t know that he was part of that crowd.